Why It's So Hard to Figure Out What the Stimulus Did

Five years after the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the biggest fiscal stimulus in the nation's history, the debate over its success hasn't changed very much.

Democrats say it worked, providing a Keynesian jump-start to the economy is a time of great distress. A White House report released on the anniversary of the Act's passage touts millions of jobs created, economic aid to families and individuals, and positive long-term growth effects, among other gains.

Republicans say it was a waste of money with little to no helpful effect. It hasn't helped the middle class, says the GOP's Senate Minority Leader, Mitch McConnell. The stimulus has "clearly failed," says Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fl.), who calls the law "proof that massive government spending, particularly debt spending, is not the solution to our economic growth problems."

All of this should sound rather familiar to those who've followed the stimulus debate, because it's more or less what the two parties have been saying for years. One reason why I suspect the debate has changed so little is that it's very hard to determine with great certainty what, exactly, the stimulus really did.

That's why I think the best way to judge the stimulus as a whole is to say that we don't really know how well it worked—but that it didn't live up to some of the promises that were made when it was passed.

In theory, fiscal stimulus juices the economy through a multiplier effect, in which one dollar of borrowed government spending produces more than a dollar of overall economic gain. With a multiplier of 1.5, a stimulus of $100 million would produce $150 million in economic activity. A multiplier of 2.0 would result in double the economic jolt of the initial cash infusion. The higher the multiplier, the bigger the boost.

The problem, as I noted in my April 2013 story on the stimulus, is that no one really knows what multiplier effect of fiscal stimulus is. Reputable economists don't even really agree about the possible range for the multiplier. Some economists think it could be in the range of 3.0 or even higher, given the right circumstances. The Congressional Budget Office puts the estimated multiplier for government purchases at somewhere between 0.5 and 2.5. A broad survey of estimates by University of California San Diego economist Valerie Ramey found that the range was usually between 0.8 and 1.5, although the data could support anywhere from 0.5 to 2.0.

Dig a little deeper into the data and it gets more complex. Estimates vary based on the timing, the economic conditions, and the particular way the stimulus funds are spent. And it's practically impossible to verify empirically, because economists can't run controlled experiments on an entire economy. They end up having to tease out the possible effects of stimulus indirectly.

You'll notice that some of those multiplier ranges actually dip below the 1.0 mark. What that means is that the economic activity created by stimulus is less than the original money spent, potentially as low as 50 cents on the dollar. Not much of a boost.

Despite the wide uncertainty surrounding these estimates, they end up playing a major role in estimates of the stimulus' effects. That's because when economists at the White House or the Congressional Budget Office attempted to gauge the results of the stimulus, they relied heavily on measurements of inputs rather than outputs, and then used the multipliers to work from there. In other words, they looked at the amount of money spent on stimulus and then ran that through a model that included an estimated multiplier.

If you build a model that assumes a high multiplier effect, then your results will reveal that stimulus spending has a high multiplier effect. What you won't have done is prove that stimulus spending has a high multiplier. But that's how the government estimates of stimulus effects on jobs and economic growth work: Rather than measure real-world results, they count the spending, assume a multiplier, and then report the output.

And what if the real-world effects were, in reality, radically different? Would that show up in the reported estimates? No. When CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf was asked, "If the stimulus bill did not do what it was originally forecast to do, then that would not have been detected by the subsequent analysis?" his response was: "That's right. That's right."

What we have then are highly uncertain, hard-to-pin-down multiplier estimates being used not to measure the results of stimulus, but to estimate what the results might be if those highly uncertain estimates happen to be correct. That's not a clear failure, but it's hardly proof of the unambiguous success the White House and its allies have claimed.

So, it's hard to say what, exactly, the stimulus did accomplish. But we can say some of what it didn't.

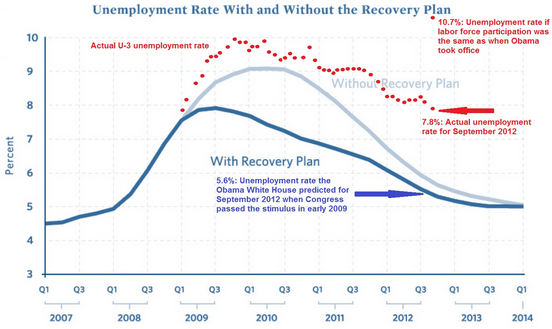

Most notably, it failed to hit the employment targets drawn up by White House economic advisers prior to the Act's passage. In a January 2009 report titled "The Job Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Plan," administration economists projected that with no stimulus in place, unemployment would continue rising through 2010, topping out around 9 percent and holding there for much of the year. With the stimulus, however, unemployment would peak in the third quarter of 2009, then begin to fall, dropping below 6 percent.

The stimulus passed, but unemployment rose higher and faster than the administration's no-stimulus track had projected. Unemployment began to fall by early 2010, but not nearly as rapidly as the administration's estimates suggested.

Via Jim Pethokoukis of the American Enterprise Institute, here's a comparison between what the administration predicted, with and without the stimulus, and what actually happened:

The administration's defenders counter that the estimate was made before the breadth and depth of the recession became clear, and that a bigger stimulus was needed. But that only reveals how hard it is to transform academic theory into practical political reality, and how easily macroeconomic turmoil is misdiagnosed by politicians and their advisers. It's hard to have confidence in their solutions when they admit they did not understand the problem. And as Pethokoukis has noted, when you factor in the dramatic decline in labor force participation, the administration projection looks even rosier.

No doubt the political back and forth over the merits of stimulus will continue, and the declarations of success and failure will end up as fodder in fights over possible future fiscal policy boosts. Not much will change. That's too bad. Because if there's anything we should have learned from the fight over the nation's biggest fiscal stimulus, it's that we've been asking the wrong question. It's not whether the stimulus did or did not fail, it's whether we can ever know one way or another—and whether it's worth spending hundreds of billions of dollars on economic interventions whose results are likely to remain uncertain.

Show Comments (123)