CBO Says Obamacare's Bailouts Might Make Money for the Government. Here's Why CBO Might Be Wrong.

Several weeks ago, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fl.) and Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer took aim at a little known provision within Obamacare known as risk corridors, dubbing the mechanism a bailout of insurers and calling for repeal.

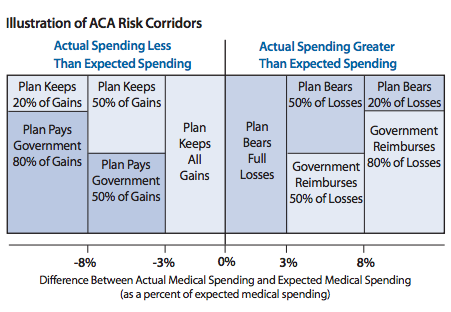

The risk corridors are a temporary program designed to share the financial risk of health plans offered through Obamacare's exchanges between insurers and the federal government. In theory, the sharing is symmetrical: If insurer expenses within those plans are lower than expected, then insurers pay the federal government a percentage of the difference between their expected target and actual spending. If insurer costs turn out to be higher than expected, because members are sicker and use more expensive medical care than predicted, the federal government picks up a chunk of the tab.

The bigger the difference between insurer costs and expectations, the more that the federal government pays out. When the law was written, the goal of the provision was to entice insurers to offer plans in the exchanges by limiting their risk exposure.

This illustration from the American Academy of Actuaries shows how it works:

The provision was generally expected to have no budgetary effect. Some insurers would end up with higher than expected costs. Some would end up lower than estimated. The payments would balance each other out.

But while budget neutrality was expected, it wasn't mandatory. If insurers paid in more than they received, it was possible that the government could actually come out ahead. But if all participating insurers ended up with higher than expected costs (say because the plan members skewed older and sicker than projected), then the result would be that taxpayers would simply be covering a chunk of insurer losses—hence, a bailout.

That possibility began to look more likely as the administration reported fewer young people signing up than hoped and as insurers indicated that exchange plans were more adverse than expected and could result in losses.

Republicans ran with the idea of ending the program, talking up the possibility of attaching it to a debt limit hike. Health insurers got nervous, issuing talking points suggesting that repealing the provision might result in insurer insolvency.

That's the backstory. But yesterday, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) added another plot point. The nonpartisan budget analysts estimated that the federal government would end up paying out about $8 billion through the program. But insurers would pay about $16 billion into the government for a net public revenue gain of $8 billion—hardly a bailout, if accurate.

So why does the CBO now believe that the risk corridor program will essentially make money for the government? Because that's what happened with Medicare Part D, the federal prescription drug program for seniors, which also relied on a risk corridor program to entice insurers to offer plans. The structure was slightly different, but in broad strokes it worked the same way, with insurers paying the government when costs came in lower than expected, and being paid when costs came in higher.

What CBO is saying, then, is that if Medicare Part D's experience with risk corridors is any indication, the government will ultimately be paid more from the program than it pays out.

So the question we need to ask is whether Medicare Part D provides a useful guide to what we can expect from Obamacare. And I think there are a few reasons to be skeptical about the notion that it does.

When the Part D prescription drug benefit began in 2006, insurers had a pretty good idea of who was going to participate. The population of seniors who might be interested in the program's drug coverage was pretty well defined, and there wasn't much reason to be concerned about high-cost individuals ditching their old plans for new ones sold through Part D. In fact, as John Goodman of the National Center for Policy Analysis pointed out in congressional testimony today, Part D actually offered subsidies to employers for maintaining existing drug insurance programs in order to keep that from happening.

Meanwhile, formerly sky-high prescription drug spending was in the midst of a significant slowdown that started just before Medicare Part D went into effect. Fewer blockbuster drugs came onto the market. The use of generics became more common. Seniors turned out to be quite value-focused when choosing drug plans.

The result was that insurers operating in Part D had relatively predictable sign-ups, and lower than expected costs. Consequently, they paid far more money back to the government through the risk corridors program than they were paid.

Is that what we should expect from insurers selling plans through Obamacare? With Huamana saying in an SEC filing that the demographic mix in its exchange plans is "more adverse" than expected, Cigna's CEO warning that his company might take a loss on the exchange plans, and Aetna's CEO bringing up the possibility that the company might eventually pull out of the exchanges? The gloomy financial outlook for exchange plans is an industry-wide phenomenon. When Moody's cut its outlook for health insurers from stable to negative to negative last month, it cited "uncertainty over the demographics of those enrolling in individual products through the exchanges" as a "key factor."

We won't know how this will work out until it does. But right now, there are a lot of bad signals. It seems at least plausible that the future of Obamacare's exchanges could look less like Medicare Part D and more like the health law's high risk pools, which ended up with a smaller, sicker, and more costly (on a per-beneficiary basis) pool of enrollees than initially projected.

CBO's score of the risk corridors relied heavily on Medicare Part D's history because the federal government doesn't have a whole lot of experience with risk corridors in the health insurance market. Given the budget office's cautious nature, it's an understandable choice. But it may not actually tell us all that much about the practical reality of the provision and its probable costs. As yesterday's report noted, "the government has only limited experience with this type of program, and there are many uncertainties about how the market for health insurance will function under the ACA and how various outcomes would affect the government's costs or savings for the risk corridor program." An experience similar to Medicare Part D's is one possible outcome. But I'm not sure it's the most likely one.

Show Comments (63)