How Calvin and Hobbes Explains the Senate Filibuster Fight

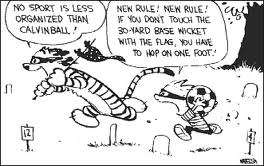

If you want to understand the procedural fight over the filibuster that went down in the Senate over the last 24 hours, it helps if you first understand Calvinball.

For those poor deprived souls who have never read Bill Watterson's classic newspaper comic Calvin and Hobbes, Calvinball is a made-up game played and invented by the two title characters. There are a slew of complicated rules associated with the game, most of which are arbitrary and some of which are utterly nutty, but the most important thing to know about the game is that any of the rules can be changed at any time, usually by any player, except perhaps when there are rules prohibiting some players from making those changes (although those rules can be changed or thrown out too, and games often end up with players making retaliatory rules designed to cancel out or complicate rules devised by other players).

It's a game, in other words, with an awful lot of complex and arcane rules that tend to evolve over time and are generally determined by the players themselves—rules that usually have to be obeyed, except when they don't.

This is not an exact description of how the Senate works, but it's close enough. And it's a reasonably useful context in which to understand the most recent squabble over the filibuster.

Members of the Senate basically get to make up their own rules, and to change them at any time. So a rule that, for example, allows the minority party to block bills or nominations that fail to get 60 votes can always be altered with a simple majority. A rule—even a rule that effectively institutes a 60-vote supermajority requirement for action—is really only as strong as a simple majority of the Senate allows it to be.

Hence the most recent fight over "the nuclear option." Senate Republicans have been relying on rules requiring supermajority support to proceed with voting to block legislation, judicial appointments, and a handful of presidential appointments. In response, Sen. Majority Leader Harry Reid, after conferring with the rest of the Senate's Democratic majority, threatened to go forward with a rules change that would have allowed presidential appointments to go through with only a majority vote. That's the nuclear option: a big change to the filibuster rules that would almost certainly lead to a serious, and perhaps total, procedural war.

This is not an entirely unheard of threat from Reid. The nuclear option, or some version of it, has been in the background of Senate procedural fights throughout the Obama administration. Nor is it a threat that Republicans have abstained from making themselves. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell talked up the possibility of invoking the nuclear option against Democrats when the GOP was in the majority back in 2005.

There's a bit of a new wrinkle this time around, which is that the legal status of some of the current crop of nominees is dubious at best. Richard Cordray, Obama's pick to the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as well as two labor-friendly nominees to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), were nominated while the Senate was in an intracession recess during a regular session—basically just a quick break. But President Obama used his recess appointment power to circumvent the Senate for their appointments. In cases focused on the NLRB appointments, two courts have ruled that recess appointments are only acceptable between sessions.

That's most likely why the primary thing the GOP got out of today's deal was a promise to take the current two NLRB nominees out of the running, replacing them with two other (presumably union-friendly) nominees yet to be determined.

The other thing that the GOP got was that Sen. Reid declined to actually go for the nuclear option. But that's not much of concession, since Reid refused to say that he would table the option permanently. He can always go nuclear at any point from now on, and more importantly, it seems more clear that, if provoked, he really will.

Going forward, this means that Republicans will have a somewhat more limited ability to use the filibuster than they have in the past, although it probably won't expand to affect legislation or judicial nominees. It also means that Republicans can be expected to use the same sort of nuclear threat if and when they gain control of the Senate, a possibility that lately looks even more likely. And my guess is that eventually Republicans will inch further toward going nuclear than Democrats have—perhaps using the nuclear threat on blockaded judicial nominations as well.

What's really shifted in the Senate is the credibility of the nuclear threat. But in some ways, very little has changed at all. As in Calvinball, the real rules are that there are no real rules, except the ones that most everyone agrees to play by.

Show Comments (72)