"Disposition Matrix" Sketched Out on How U.S. Decides to Kill Citizens

Pieced together based on what's known about American counter-terror efforts

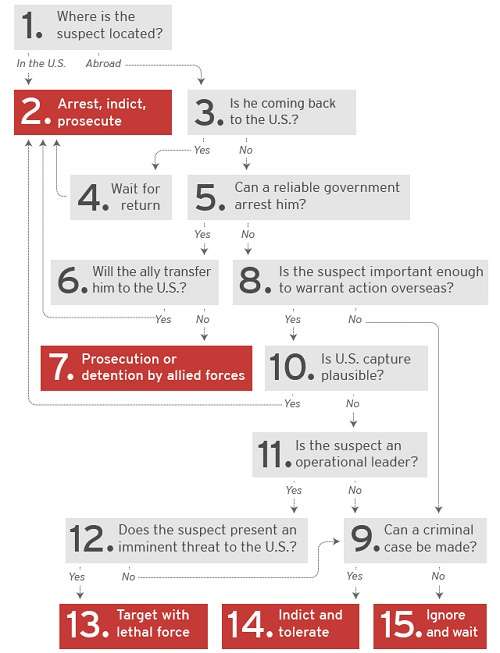

As noted on Reason 24/7, a federal judge has summarily dismissed FOIA requests by the New York Times and the ACLU for the legal justification used by the White House to order the killing of U.S. citizens. While officialdom is relatively silent on the workings of America's drone war, the work to piece together how the U.S. might be operating based on what we know it's doing continues. At the Atlantic Daniel Byman and Benjamin Wittes, fellows at the Brookings Institution, put together a "disposition matrix" of how the U.S. might go about deciding which U.S. citizens it suspects of terrorism it could/should kill.

Byman and Wittes note that in fact "the domestic criminal justice system is actually one of the workhorses of American counterterrorism" and so arrest, indictment and prosecution is the most common path along the flow chart (#2 if the target is in the United States). The next terminal point, "prosecution or detention by allied forces" might be better known as rendition. One U.S. citizen sued in 2009 after being captured in Kenya two years earlier. The 2011 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) made it easier for the government to rendition U.S. citizens.

The most serious terminal point, "target with lethal force" (#13), has only been reached once, that we know of, by the White House, when Anwar al-Awlaki was targeted in a drone strike in Yemen. Al-Awlaki was alleged by the U.S. government to have been an "operational leader" of Al-Qaeda, and Eric Holder insisted afterward that the U.S. can kill citizens when they present an "imminent threat," though what imminent threat al-Awlaki might have posed has never been revealed. Of note, also, is the death of his teenage son, a U.S. citizen as well, in another air strike two weeks later. At first the government insisted al-Awlaki's son was a 21-year-old Al-Qaeda fighter, but the Washington Post later printed his birth certificate. Robert Gibbs, working for the Obama campaign, suggested the teenager ought to have had "a far more responsible father." There are no indications that the teen was an operational leader or an imminent threat. As for the elder al-Awlaki, he had never been indicted for any terrorism-related charges by the U.S., and the most prominent terrorist act he's been associated with in the press was the shooting at Fort Hood, which the U.S. government does not classify as a terrorist attack but an incident of workplace violence (Major Nidal Hasan is currently on trial in military court for the shooting spree).

The New York Times detailed some of the inner workings of the White House's drone war last year.

Show Comments (86)