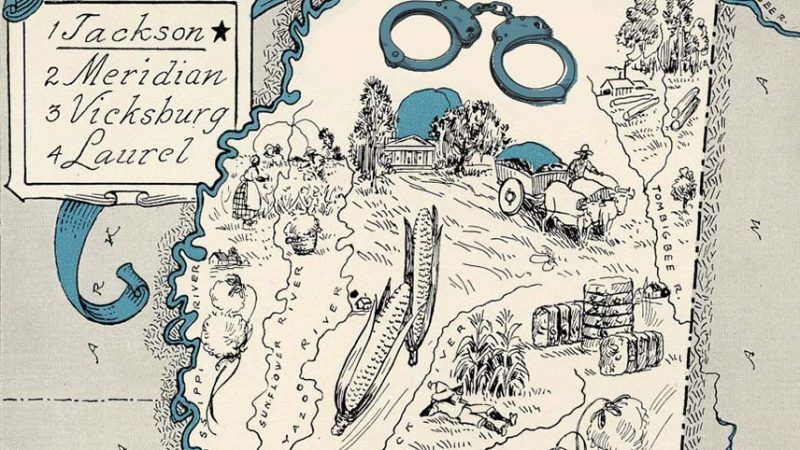

Mississippi's Jump-Out Boys

The police punish people for living in a bad neighborhood.

Betty Jean Tucker, a 62-year-old resident of Canton, Mississippi, says she was hosting a barbecue for family and friends in 2014 when several unmarked cars appeared. Plainclothes deputies from the Madison County Sheriff's Department (MCSD) jumped out. Without a warrant, they detained and searched all her guests, going so far as to rummage through everyone's pockets, she says. After finding nothing, the deputies got back in their cars and drove off without explanation.

It wasn't the first time Tucker had a run-in with the MCSD. About five years ago, she says, her teenage grandson was in her front yard, fixing his brother's bicycle, when an unmarked truck sped toward him and stopped. Two plainclothes officers jumped out, tackled him to the ground, and searched him. Again finding nothing, the deputies left. Tucker shouted at them, asking what he had done. "Tell your grandson to wear a shirt next time," they allegedly replied.

Tucker is now a named plaintiff in an American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) class action lawsuit against Madison County. The suit, filed in May, alleges that the sheriff's department and its plainclothes "jump-out" squads systematically target and violate the Fourth Amendment and 14th Amendment rights of residents like her just for being black and living in the wrong place.

The dozens of similar stories unearthed in the ACLU's suit and a subsequent Reason investigation are stunning, but the Madison County Sheriff's Department's tactics are not unique. Paloma Wu, a Mississippi ACLU attorney, says they only represent a "sharpened iteration" of the methods used widely in other places across the country.

The ACLU is also suing Milwaukee for its high-volume stop-and-frisk program, which the civil rights group says subjects minority residents to suspicionless searches. Milwaukee Police Chief Ed Flynn is a disciple of "broken windows" policing—the theory that a heavy police presence in a community, combined with proactive enforcement of low-level nuisance crimes, will deter more serious offenses. Under Flynn, the combined number of police traffic and pedestrian stops in Milwaukee nearly tripled in an eight-year period, rising from 66,657 in 2007 to 196,434 in 2015, according to the lawsuit. And minorities bear the brunt of that saturation policing.

Flynn argues the strategy logically focuses on areas with the most crime. In practice, however, community activists and civil rights groups say these strategies make minority residents feel like they're under siege from police.

It's also expensive. In 2016, the city of Milwaukee paid out $5 million to 74 black residents who said they were illegally strip-searched.

If nothing else, the policy hurts relations between neighborhoods and police. Earlier this year, the Baltimore Police Department declared that it was ending its use of plainclothes police known as "jump-out boys" or "knockers" by locals. The announcement came after the federal indictment of seven Baltimore plainclothes officers on charges of robbery, extortion, racketeering, and filing false police reports.

The Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C., used to have an aggressive jump-out squad that operated in the poorer wards of the District, but the city disbanded these vice squads amid community complaints in 2015. "Half of the time, they pull you over, or if you walking and they stop you, [it's because], oh, you fit a description," a black high school student in southeast D.C. told Politico that year. "A million people got black hoodies, black jeans and black shoes. Why it got to be me?" When the reporter asked a group of students if they ever felt relieved when they saw the police, she was met with a chorus of noes.

But while these programs are under scrutiny in urban environments, they often persist unchallenged in rural areas and smaller cities. In Mobile, Alabama, the police department announced in June that it would be setting up mandatory "safety checkpoints" in high-crime neighborhoods, despite community complaints that the roadblocks disproportionately affect minorities.

Citizens in an affluent neighborhood would rain hell on every public official in town if they were subjected to illegal stops and unconstitutional pat-downs, and rightly so. Why do we expect others to tolerate it just because of their zip code?

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Mississippi's Jump-Out Boys."

Show Comments (42)