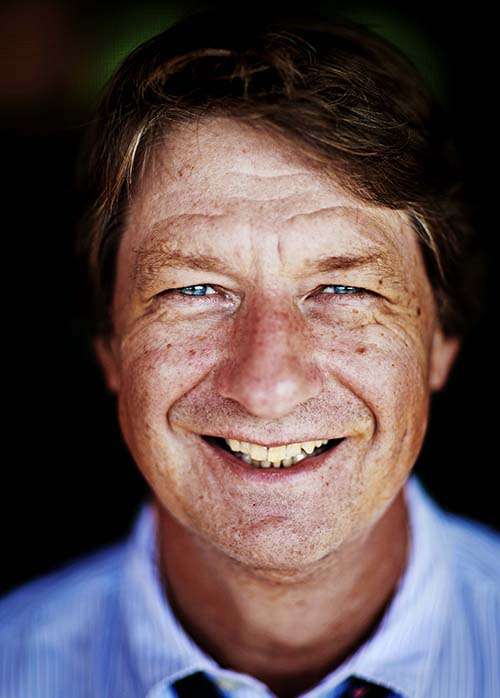

P.J. O'Rourke: Things Are Going to Be Fine

But there's going to be some trouble getting to the fine part.

"The politician creates a powerful, huge, heavy, and unstoppable Monster Truck of a government," P.J. O'Rourke writes in his new book, How the Hell Did This Happen? (Atlantic Monthly Press). "Then supporters of that politician become shocked and weepy when another politician, whom they detest, gets behind the wheel, turns the truck around, and runs them over."

In the book, O'Rourke's 19th, the former editor in chief of National Lampoon uses his celebrated blend of acerbity and warmth to explore the 2016 election, which he refers to as a "rebellion" against people in control. O'Rourke, a regular panelist on NPR's Wait Wait…Don't Tell Me!, worries our changing economy is fueling a populist wave of fear and anger. "There's a segment of America that feels threatened by change, change of all kinds," he says. Still, he's optimistic for the future. His kids might have three or four careers over the course of their lives, but "I think they're pretty hip to that, actually. I don't think that they're particularly frightened by it."

In March, Reason's Nick Gillespie spoke with O'Rourke by phone about what he saw on the 2016 campaign trail, what it means for the country, and how libertarians should respond to this new populist moment.

Reason: Do you consider yourself more of a libertarian or a conservative? Where do you see the border between those concepts?

O'Rourke: It really depends upon from what angle we're looking at things. Politically, I consider myself primarily to be a libertarian. I am personally conservative. I'm conservative about religion. I'm conservative about moral values. I'm probably even somewhat more conservative than many libertarians are in foreign policy.

When you look at something that happens, especially in politics, you say, "Does this increase the dignity of the individual? Does this increase the liberty of the individual? Does this increase the responsibility of the individual?" If it meets those three criteria, then it's probably an acceptable libertarian political policy.

What is good about the new populism for you, and what scares you about it?

Well, let's talk about the good, because it's more limited. I think there's a worldwide animus going on against the elites. Part of this is that the shift toward a much more high-tech economy is leaving a lot of people who have manual skills, or simply the capacity for hard labor, way behind. This is something that needs to be addressed, needs to be recognized, because it's not so much that the divide between the rich and poor has gotten greater. There's actually been tremendous strides around the world at abolishing the worst level of poverty. But [people are] feeling a sort of aspirational ceiling. The fact that a lot of it has to do with lack of rule of law in places—not only in utterly chaotic places like, say, Somalia or Sudan, but in very corrupt places like Russia and China—is making people very angry. Rule of law is something that's fundamental to a free society.

Define rule of law. Do you mean that the same rules apply to everybody?

Exactly, and you can sort of extrapolate from this that it doesn't have to be perfect law. That as long as the rules of the society apply to everybody, there is a kind of justice in the air. But when there's an exception because of wealth or power or holiness or fame, you name it—if there is a mechanism by which somebody can step outside the justice department—then that law is lousy no matter how liberally written.

What about countries like France, Hungary, Russia, the United States, England? These are also places that are experiencing real paroxysms of populism.

I would say there are a couple of things going on. One thing sets us apart from Europe: Europe is suffering from a tremendous refugee crisis that the governmental elites have completely failed to address. They've failed to address its cause. They've failed to address its effects. They've failed to address its aftereffects. They have just completely screwed things up, and I think that probably holds the key to the Brexit vote.

NPR did an exit poll where they went around to places that had voted heavily for Brexit, and pretty much across the board, [the response] wasn't racist, it wasn't violent, it wasn't xenophobic, but it was, "This isn't the Britain that I grew up in. Things are changing."

Here [in the U.S.] I think it's more directly an effect of expansion of government to the point where government just has its thumb in every conceivable pie. I mean, we are so complexly regulated that it's driving people crazy, and the people it's driving crazy are the core [Donald] Trump voters. They tend to be small-business people, often highly skilled blue-collar [folks]. Their incomes wouldn't indicate that they're blue-collar. Their education might not.

These are craftsmen, or…?

Yeah. The plumbers and electricians, and maybe master electricians, master plumbers.

Trump was not my choice, but I was talking to a guy [at a Trump rally] and he said, "I own a gas station and a towing operation. It's just me and my wife. I don't have a human [resources] department. I don't have a legal department." He said, "Every time some jerk in Washington passes some new idea, he never seems to think that it means another pile of paperwork on my desk." He said, "I've got old gas tanks at my gas station, and I can't get the local, state, and federal permits to get them removed. I can't get the local, state, and federal permits to install new ones. I'm regulated from every conceivable direction." He had a fair number of employees, and he said, "I can afford the Obamacare. But what I can't afford is the paperwork that comes with it. That's not what I do." I really liked the guy and finally I said to him, "So electing a maniac fixes this how?" He laughed. He said, "I don't know, but the hell with the bunch of them. I'm voting for Trump."

"At the core of libertarianism—as an attitude and as a way of thinking about politics—is the idea that people are assets. The liberal idea is that people are burdens."

You endorsed Hillary Clinton and said you wouldn't vote for Trump.

No, and I did vote for Hillary.

How did that feel?

OK. It was a matter of, if I may say so, reason. You know, in the commodity market there's something called the VIX, the volatility index. They call it the fear index. You can actually buy and sell fear on the commodity index. I looked at the volatility of the two candidates, and I thought, "I know with about 98 percent, 99 percent assurance exactly what I'm getting with Hillary. I loathe and detest it, but we just survived eight years of it. I doubt it will last more than four more." It's very rare for American political cycles to last longer than 12 years, as poor George H.W. Bush proved.

I looked over at Trump, and I said, "I have no idea. I just have no idea. He might turn out to be an absolutely ordinary president. [But] I don't like this populist noise." If I had to put one finger on a thing about Trump, it was the scapegoating, the stuff about refugees, the stuff about immigrants, and so on. I'm a pro-immigrant guy. I will listen to anti-immigrant talk from a full-blooded American Indian and nobody else. They've got a beef.

Let's talk specifically about Trump. What frightens you most about him?

This is just not a small-government guy. This is a big-brushstroke person, and I don't have any use for that. I want the government to shrink in the wash. I want it both cleaner and smaller, please.

And whiter? Is that where you're going?

As a matter of fact, if anything, I want the nation to be more colorful. At the core of libertarianism—as an attitude and as a way of thinking about politics—is the idea that people are assets. The liberal idea is that people are burdens. More sick people means more government expense. More poor people means more government expense. More any kind of people means more government expense. Whereas I think it means more growth, more vitality.

But Democrats are going after Trump with everything they've got.

They sure are. But the point of the fact is, he's one of them.

Explain that a little bit.

He's one of them, but he's coming at it from a sort of populist [direction]. There's a segment of America that feels threatened by change, change of all kinds, and he's saying, "Well, I'm going to make things like they used to be." But the tools that he's going to use—huge infrastructure spending, Big Digs everywhere, the huge rise in military budget. We already spend more than, what is it, the other top 10 countries combined? We may have a foreign policy that doesn't make any sense, but you don't want to mess with our military. He's a big-government guy for small-minded people, and the liberals are so mad at him because they regard themselves as large-minded people, but of course they're equally big-government.

Something else somebody said to me on the campaign trail at a Trump rally was, "Damn it. I'm in the logging business. I am so regulated." And at the end of it he said, "I turn on the TV at night, and what's the lead news story? It's about transgender bathrooms. We don't have any bathrooms in the woods."

"I will listen to anti-immigrant talk from a full-blooded American Indian and nobody else. They've got a beef."

You talk about populism as a libertarian tragedy. How did you answer the guy who was pissed about the transgender bathrooms on the news?

I was just there as a reporter, so the way I responded to him was by writing what he said down.

You need somebody who is really good at getting this stuff across, the way Ronald Reagan was. I would prefer things to be so that I could tell you, "We have to do more libertarian education. We have to do more libertarian outreach. We've got to get younger people who have libertarian inclinations more engaged in this." In fact, it requires the kind of leadership that was not provided by [2016 Libertarian Party presidential candidate] Gary Johnson.

He was not inspiring?

He just ran a terrible campaign. There were so many moments, it seemed to me, over this campaign cycle that lasted for two years, when libertarian stuff could catch fire, and it didn't. I had some hope for [Kentucky Sen.] Rand Paul, but Rand is unfortunately burdened by intellect. You ask Rand a question and you get the whole answer. While that's great for an interview, it's not great on the stump. You don't get the joke that you got from Reagan. You don't get the thing boiled down.

In some of your writings, you talk about how the pace of technological change seems different over the past, say, 30 or 40 years, and that in the digital era, change is more disruptive. What's going on?

First there was an agricultural revolution in the late Middle Ages, which arguably led to the Renaissance. Adam Smith makes that argument in The Wealth of Nations. Then of course was the Industrial Revolution. The thing we have to understand about those revolutions was that they were slow. Especially the Agricultural Revolution. It was very gradual—so gradual that it wasn't until a couple of hundred years later that people really could realize that it had happened.

The Industrial Revolution was much faster, but it worked on very basic principles of mechanics [so] that your average plowman could look at this machine and see how it worked. It was linear. Once you had seen a railroad, how surprised could you be by an automobile, which is a locomotive off its track? The Industrial Revolution was comprehensible to people. It happened fairly quickly, but not nearly as quickly as the [information technology] revolution, or the electronic revolution, or the internet revolution, or whatever you want to call it. And the side effects of this very quick technological change have been exceedingly unpredictable. I mean, who at the onset of the internet would predict that it would make the anchor store at the local mall go away? It has these totally surprising effects on people's lives and their jobs, and it spreads fear, even to people who have nothing to fear.

Libertarians are often accused of being descended from Vulcans and not having any emotions. How do you put the humanity back into that disruption? Because you're explaining extremely well where the populist anger comes from, but we also don't want to deny the fact that Amazon is a great service.

Absolutely. We all use it. We're voting with our fingers. We're voting with our credit cards. We're all in favor of it, obviously. It cost us a job at one end but got us a cheap couch at the other.

I think this is one of the reasons that this was a very tough election for libertarians, because it's hard for libertarians, who are in favor of progress, who are in favor of innovation, and who are in favor of free enterprise, when disruption is caused by these fundamentally good things—macro good things. But when they're causing disruption at a micro level, maybe we sometimes have to rethink, a little bit, our position of utter non-interference in people's lives.

This certainly would be a time for libertarians to get in there and work hard on getting rid of the kind of regulations that put undue limits on any kind of free enterprise. Small businesses shouldn't be penalized for growing. They shouldn't be zoned out of existence. They shouldn't be regulated out of existence. It's time to do that. And maybe there are rational government interventions, not to prevent any of these [examples of progress] from happening, but to ease the circumstances under which they happen.

That could be a different type of social safety net than libertarians historically are comfortable with, or universal basic income, or…

Yeah, it could be something in that direction.

I don't pretend to be enough of a policy wonk to say which of these things would be best or not best. I leave that to the scholars at the Cato Institute and places like that. But I have a feeling that comfort can be given, and aid and assistance. So many kids are coming out of the educational system ill-prepared for this modern economy. Right there with school vouchers, you've got a good issue.

Are you optimistic? Most libertarians I know feel like in the long run, things will just get better and better. But what about the medium run? Are your kids going to have to learn three or four different professions over the course of their life?

I think they're pretty hip to that, actually. I don't think that they're particularly frightened by it. They of course have a capacity, that I at my age don't, to embrace change enthusiastically. When you're a 13-year-old boy, any change is good change. "Hey, the house is on fire." Everything is exciting.

I am actually very optimistic. But of course I've had the good fortune—and this had to do with making a decent income and also with the person I married—to ensure that my kids are getting a good education. They're going to be prepared, both specifically with certain skills, but also intellectually, generally, to cope with the change.

One model we can look to is Europe, which we might be 20 years behind in terms of the populist uprising. But then there's Japan, which has fewer people now than it had at the turn of the century.

I don't think either of those are appropriate models for us. I mean, Europe is so ingrained with its factionalism and its proximity to all sorts of ugly customers. You can practically walk to war from anywhere in Europe.

Japan is such an isolated, insular society. For all the talk to the contrary, we're immigrant-friendly and we're an immigrant nation. And while we do have plenty of factions, they do all speak more or less the same language and are not divided up the way that Europeans are. Nor do we have this sort of royalist attitude that all good things rain down upon us from the government, which still obtains in these ex-royal countries. Even in France, where you'd think they would know better.

I think things are going to be fine, but there's going to be some trouble getting to the fine part, and libertarians, we may be fighting some old battles.

You mean that we're fighting over entitlement spending and things like that?

Yeah. I mean, these things absolutely have to be addressed, and libertarians are in a very good position to address them. But when it comes to changes in the nature of the relationship of the individual to the state, many of us—and I include myself—we're still fighting the fights that Milton Friedman, [Friedrich] Hayek, and so on fought. I'm not saying that those fights don't still need to be fought, but I'm saying there are also other battles that we better get ourselves involved in.

What is the first among those other battles?

The first at this moment is economic transition. How do we enable this economy to benefit most from the changes that are going to happen anyway?

That's where you're talking about getting past a lot of accreted regulations. In a way, I guess Trump is speaking your language when he says, "For every regulation we pass, we're getting rid of two."

Yeah. Not a bad idea. The man is not without some insights. I don't know if I'd go so far as to call them ideas, but he perceives some things.

Your last big book was about the baby boom generation, your generation. Is there any part of you that's sad over Bill and Hillary Clinton exiting the stage of national and world politics?

Not one iota. It's "Goodbye, and don't let the door hit you on the butt on the way out," you know? "What's your hurry? Here's your hat."

This interview has been edited for length, clarity, and style. For an audio version, subscribe to Reason's podcast.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "P.J. O'Rourke: Things Are Going to Be Fine."

Show Comments (74)