How Citizens United Protects a Mezcal Company's Right to Critcize Donald Trump

Corporations, free speech, and why "Donald eres un pendejo."

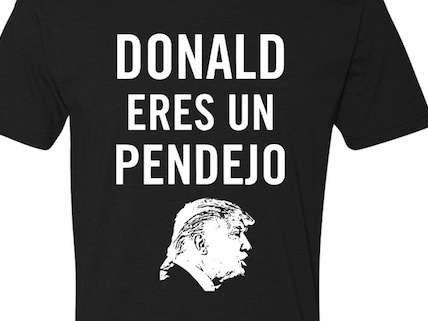

Way back in July 2015—yes, the election really has been going on that long—thousands of posters bearing the likeness of Donald Trump and the words "Donald eres un pendejo" began appearing around New York City. (That's "Donald, you are an asshole" for those who don't speak Spanish or have never worked in a restaurant kitchen.)

The posters were the work of Ilegal Mezcal, a brand of agave spirit imported from Mexico. John Rexer, owner of the brand, was inspired to put up the posters after a conversation with a Mexican waiter who was dejected by Trump's anti-immigrant rhetoric. The phrase has since become closely identified with Ilegal, which has printed it on posters and t-shirts and even projected the image onto Rockefeller Center. The brand has also put on events encouraging drinkers to "take a shot at Trump," donating $2 for every shot of mezcal sold to an educational charity in Guatemala.

Trump's anti-immigration stances have been so uniquely reprehensible that even larger brands such as Aeromexico, Tecate, and Corona have addressed them, though typically in a more oblique fashion than Ilegal. "It takes some degree of risk for a brand to take a political point of view but I think Mexican brands have a responsibility to their own people," Rexer told the Guardian. "They do business with the US, and they should be concerned with [Trump's] tone, that not only affects them business-wise but also affects the bigger picture."

Messaging like Ilegal's has struck a chord, but it's also in tension with the idea, popular on the political left, that corporations should not engage in political speech. Since the U.S. Supreme Court's Citizens United decision in 2010, it has become common for liberals to assert that corporations don't have free speech rights, that money is not speech, and that corporate expenditures intended to influence politics can be restricted unproblematically. A question worth asking then is: Would a hypothetical President Trump have constitutional authority to forbid mezcal companies from calling him a pendejo?

Nothing that Ilegal has done so far would have violated election laws as they stood before Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. At the time of the decision, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act applied only to broadcast, cable, and satellite communications that explicitly mentioned a candidate by name. But if that decision had gone differently, it's also easy to imagine election laws being extended in ways that would have a chilling effect on advocacy.

The issue was brought up in a memorable exchange with the Department of Justice's Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart during initial oral arguments before the Supreme Court. Justice David Souter asked whether there was any limiting principle that would exclude even books from being censored by the Federal Election Commission. If a labor union, for example, wanted to use its treasury funds to hire an author to write a book that explicitly argued for or against a candidate, could the government take action against it? "I think it would be constitutional to forbid the labor union to do that," Stewart conceded.

The complexity of the case prompted an unusual second round of oral arguments in which Elena Kagan, then solicitor general, stepped in to argue the government's case. Asked by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg if it was still the government's position that the FEC's powers could extend to books, she reversed positions. "The government's answer has changed," she said to laughter in the Court. But pamphlets, which Kagan called "pretty classic electioneering," certainly could be covered.

Of relevance to Ilegal's posters insulting Donald Trump, the initial oral arguments made it clear that signs paid for by corporations could be banned as well. "I suppose a sign held up in Lafayette Park saying vote for so and so. Under your theory of the Constitution, the prohibition of that would be constitutional?" asked Chief Justice John Roberts. "[If] by prohibition you mean ban on the use of corporate treasury funds, then, yes, I think it's absolutely clear," answered Stewart.

Had the government's theories prevailed in Citizens United, there would be no constitutional barriers preventing Congress from banning speech exactly like Ilegal's poster campaign. "Let's be really clear: It is publicity and I did use company money for this," Rexer told Vice last year. The government would argue that such speech was protected only by the discretion of Congress and the FEC to focus on radio and TV. But if they wanted to go further? Under the federal government's theory in Citizens United, the First Amendment wouldn't stand in their way.

The current election has demonstrated that both major party candidates would very much like to go further in the restriction of political speech. Donald Trump wanted the Federal Communications Commission to levy fines against commentator Rich Lowry for criticizing him on TV; Trump threatens newspapers that report on his sexual assault allegations with lawsuits for libel; he suggested he would pay legal fees for supporters who rough up protestors at his rallies; and, of course, he says he wants to reform campaign finance.

The last of these is a desire he shares with Hillary Clinton. The original impetus for Citizens United was Hillary: The Movie, a conservative documentary that a court had ruled to be illegal political advocacy by a corporation if distributed by video-on-demand. "Citizens United, one of the worst Supreme Court decisions in our country's history, was actually a case about a right-wing attack on me and my campaign," Clinton said during a speech conceding the New Hampshire primary to Bernie Sanders. "A right-wing organization took aim at me and ended up damaging our entire democracy. So, yes, you're not going to find anybody more committed to aggressive campaign finance reform than me." That campaign finance laws allow politicians to silence their critics is a point usually brought up by opponents of reform, not by its supposedly nobly motivated advocates. Clinton has since pledged to introduce a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United within her first 30 days in office.

Calls for overturning Citizens United inevitably portray it as a means of restricting large corporations spending millions of dollars, but election laws apply to small companies too. If anything, small companies would bear the burden of compliance even more heavily; a large corporation can bear the risk and expense of maintaining a separately funded political action committee far more easily than, say, an artisanal spirits company. As the majority opinion of Justice Anthony Kennedy rightly concluded, such regulations can have a chilling effect on speech, nudging potential speakers to stay silent rather than chance the fines and jail terms that can accompany violations of election law.

It's better for them to know that their independent expenditures on political speech are protected. It's looking increasingly unlikely that Donald Trump will win the presidency, but the fact that the thin-skinned demagogue is as close as he is should serve as a reminder that leaving First Amendment rights to the discretion of elected officials charts a perilous course.

Ilegal's example cuts against the view that corporations don't have First Amendment rights and that money is not speech. If you believe that those oversimplified slogans are true, it's hard to argue that Congress couldn't choose to limit the kind of activity Ilegal is engaged in.

On the other hand, if you believe that Ilegal's campaign is exactly the kind of speech the First Amendment was designed to protect, that it represents a sincere expression of belief by the owner and employees of Ilegal Mezcal, and that restricting their speech would violate their rights, you might have more in common with the conservative wing of the Supreme Court than you realize. So if you raise a glass of mezcal in protest against Donald Trump, consider also offering a toast to Anthony Kennedy, John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito for protecting all speakers' right to call Trump a pendejo.

Editor's Note: This article originally misidentified Solicitor General Elena Kagan's title during the Citizens United oral arguments.

Show Comments (183)