How Political Extremism Sways Presidential Elections and Public Policy

Models of American electoral behavior suggest that Clinton should lose, but worries about extremism may Trump

"Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice," Barry Goldwater famously declared as he accepted the Republican presidential nomination in 1964. I have never really understood why some people thought those words were beyond the pale. Yet some more anxious and thoughtful souls worry that such "extremism" might possibly provoke people to engage in murderous mayhem.

So how does political extremism play out in American politics? One new study shows that extremist arguments can be effective in shifting public policy debates. Another reports that voters do not penalize more ideologically extreme presidential candidates.

"Exposing people to extreme conservative policies makes them more likely to prefer moderate conservative policies relative to liberal ones, and vice versa," reports the New York University political scientist Gary Simonovits. Simonovits' study, which was published in the journal Political Behavior, is basically an empirical confirmation of how the "Overton Window of Political Possibilities" works.

As Simonovits explains, Joseph Overton was a libertarian policy analyst at the Mackinac Center who "argued that the range of policies or opinions deemed acceptable by the public is in a constant flux and can be shifted by introducing and defending ideas not yet 'on the table.'" Or as Daily Kos blogger David Atkins once summarized it: "You win policy debates by crafting arguments for extreme positions—and then shifting the entire window of debate."

Simonovits tested this claim by deploying surveys that make statements about various policy proposals along the standard left-right political spectrum. Some were designed to be more centrist and others are more extreme. (He defines extreme positions as "those far from the policies that mainstream political actors stand for in a given time and place.") The goal was to see how exposure to the extreme policy proposals affects the participants' views.

In one survey, participants read centrist liberal and conservative policy statements saying it should be made somewhat easier or harder to immigrate. Extreme liberal and conservative versions stated that immigration should not be limited at all or should be banned, respectively. In another survey, the centrist policy statements proposed slight increases or decreases in welfare; the extreme ones said welfare should be radically increased or entirely abolished. In another, the centrist statements argued that abortion should be legal in most cases or illegal in most cases; the extreme positions held that it should be either always legal or entirely banned. In the last one, the centrist arguments held that the federal minimum wage should be increased to $10.10 or kept at $7.25; the policy extremes involved increasing it to $15.10 or reducing it to $5.10.

After running these surveys on about 4,000 participants, Simonovits reports, "Moderate conservative polices were perceived as more centrist when an extremely conservative alternative was introduced; likewise, respondents rated moderate liberal alternatives as significantly more centrist when an extremely liberal policy was added to the choice set." For example, respondents exposed to the proposal that welfare be abolished were more likely to see the idea of somewhat reducing welfare spending as more centrist than the idea that it should be increased somewhat. Simonovits found the same effect for each of the policy statements he surveyed. The relatively small effects in these one-off surveys suggest that political entrepreneurs do have a real hope that by continuously hammering their issues they can eventually get them "on the table" of mainstream policy discourse.

Received wisdom of the pundit class is that American presidential candidates must run to the center in order to win, because wary voters punish candidates who are perceived as extremists. The landslide losses of Goldwater and Democrat George McGovern are supposed to be the prime examples of this phenomenon. The Holy Cross College political scientist Donald Brand expressed this conventional view when he wrote in July that Clinton "has run to the left in the primaries to counter the challenge posed by Bernie Sanders, but she will almost certainly moderate and run to the center in the general election."

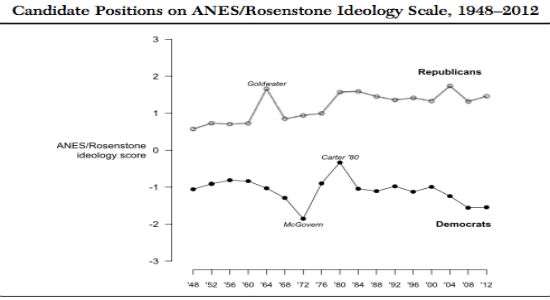

A new study by James Madison University political scientist Marty Cohen and his colleagues call this conclusion into question by looking America's presidential elections from 1948 to 2012. The researchers devised a measure of ideological extremism for each of the major-party presidential candidates, and then tried to determine whether ideology helps to predict electoral outcomes.

Cohen and company tested their ideology measures using two well-known models for predicting presidential vote outcomes: "musical chairs" and "bread and peace." In the musical chairs model, voters focus on whether economic growth is robust leading up to the election—and they tend to tire of an incumbent party over time. Bread and peace includes a penalty for going to war unprovoked.

Without going into great detail, Cohen and his colleagues created an ideology scale for every major-party candidate from 1948 to 2012 relying chiefly on survey data from the American National Election Studies and the Rosenstone political location scale.

Running the perceived relative extremism of the candidates through both predictive models the researchers find a very modest contribution of ideology to the outcomes of presidential elections since 1948. The biggest effect they find is that concern over Reagan's conservative ideology might have delivered an extra 1.3 percent of the votes to Carter in the 1980 election. Nevertheless, Reagan won 51 percent of the popular vote and 90 percent of the Electoral College.

So what about the conventional wisdom that ideology caused the landslide defeats of extremists Goldwater and McGovern? The researchers point out that both "faced a double whammy." Both the musical chairs and bread and peace models predict that one-term incumbents overseeing a rising economy will win. So Johnson and Nixon did in 1964 and 1972, respectively. They further note that perceived ideological extremists Reagan (1980) and Obama (2008) won handily when challenging incumbent party candidates with poor economic records. The upshot is that Americans care most about economics and war when they the cast their ballots.

So what do these studies suggest about the outcome of the presidential election on November 8? If the predictive models are working, then Hillary Clinton should be losing due to weariness with the incumbent party and a relatively lousy economy. On the other hand, Donald Trump's extremist ideology—if you can call the mish-mash of his often contradictory diatribes an ideology—may undermine the claim that ideology plays essentially no role in determining the winners of American presidential elections.

On the more worrying other hand, Simonovits' research suggests that Trump's extreme anti-immigrant, protectionist, anti–free speech, pro–surveillance state, and racially divisive tirades may have the effect of shifting the Overton Window toward mainstreaming radically anti-liberty politics.

Show Comments (64)