Gay Activists vs. Barack Obama

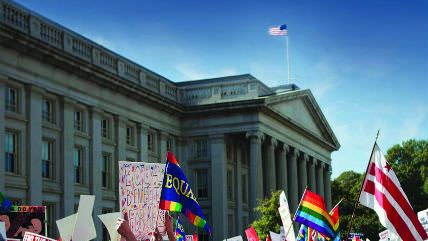

How a minority movement pushed a reluctant president to act

Don't Tell Me to Wait: How the Fight for Gay Rights Changed America and Transformed Obama's Presidency, by Kerry Eleveld, Basic Books, 368 pages, $27.99

It's hard to believe how much the political and cultural environment for America's gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender citizens has transformed during the presidency of Barack Obama. In 2009, the U.S. military was still requiring members of the armed forces to remain in the closet if they were anything but heterosexual. Only Massachusetts and Connecticut legally recognized same-sex marriages. (California had briefly joined them, but Proposition 8 put a stop to new weddings the same night Obama was elected.)

In 2015, gay and lesbian members of the military may serve openly, and the Pentagon is putting together plans to accommodate transgender troops by 2016. Same-sex marriage is now the law of the land, both on the federal level and in each state. Federal hate crime laws were expanded to include sexual orientation and gender identity. Federal contractors are forbidden by executive order from discriminating against gays. And during Obama's presidency, polls showed American support for recognizing same-sex marriage passing and staying beyond the 50 percent threshold, a broad signifier of cultural shifts. When Obama leaves office, he will surely hold up this legal and cultural sea change as one of his administration's major successes.

But how much credit does he deserve? In Don't Tell Me to Wait, Kerry Eleveld, a former political reporter for the gay magazine The Advocate, argues that it was relentless pressure from activists that forced the administration to take actions it might otherwise have tabled. Her account depicts a president and party establishment struggling to catch up with the pressure to change, not leading it.

Eleveld, who covered Obama's first term in Washington, is known for landing the gay press's first campaign interview with the future president. That interview, significantly, had its origins in gay frustrations. While Obama had been calling for equal rights for gays and lesbians, he objected to same-sex marriage, advocating separate-but-equal "civil unions" and for letting individual states dictate their own terms.

Candidate Obama vacillated between appealing to gays and lesbians, a traditional if small Democratic constituency, and religious voters, a much more sizeable bloc that went heavily Republican in 2004. When his campaign put together a gospel tour to appeal to voters of faith, one of the entertainers selected was Donnie McClurkin, a black singer who had publicly struggled with his sexual orientation and came out of it believing that God can cure homosexuality. McClurkin's inclusion started a firestorm among gay activist groups. After hearing their objections, Obama's campaign refused to cut McClurkin but tried to balance him by adding a gay minister to open the tour with a prayer. But the minister chosen was white, which just fueled the fire by making it look like the fight was between gay whites and religious African Americans.

So by the time Eleveld first interviewed Obama, the senator was on the defensive. "The candidate seemed to feel misunderstood, or perhaps unappreciated for his actions," she recalls. It wouldn't be the last time.

"Obama's greatest weaknesses on LGBT issues," Eleveld writes, included "his inability to digest negative feedback. He viewed himself as a progressive, certainly on most social issues like LGBT rights. And he seemed to feel so secure with the fact that he was doing the right thing by gay people that he couldn't accept the suggestion that he may have done the wrong or hurtful thing."

Don't Tell Me to Wait is not fundamentally about the president. It's about the very specific, targeted activism that forced his administration to proactively push for the gay-friendly causes Obama had campaigned on. Eleveld's role as an activist/journalist gives her a good vantage point from which to tell this story. On one hand, she was in contact with members of the administration and the major gay groups. But she was also in tune with the increasing audience and attention given to bloggers, and she tracks the start of new activist efforts like GetEqual, an organization inspired by the tactics of ACT UP and Code Pink, to openly confront the administration whenever it failed to push forward.

Those new activists had their work cut out for them. It may be forgotten in the wake of so many recent gains, but Obama frequently stumbled on gay issues early on.

During the 2008 campaign, then–Sen. Obama spoke with the evangelical pastor Rick Warren at Saddleback Church in California and defended the idea that marriage must be between a man and a woman. The proponents of Prop. 8—a state-level constitutional amendment to define marriage as between a man and a woman—used this appearance to encourage voters to strike down gay marriage in liberal California. The fact that Obama opposed Prop. 8 was lost, but it was arguably an irrelevant distinction: The candidate had said he supported states determining their own gay-marriage rules and that he personally believed marriage was between a man and a woman.

Prop. 8 passed the same day Obama was elected president. This combination of a national progressive victory and a local gay-marriage defeat prompted much soul searching and rethinking on the part of gay activists. One of the key characters in this part of Eleveld's narrative is Robin McGehee, a Fresno woman who would go on to help found GetEqual. It's not enough to argue against conservatives, McGehee and others realized. They also faced institutional inertia and a Democratic Party afraid of politically risky decisions, even within prominent establishment gay organizations like the Human Rights Campaign (HRC).

Rather than openly confronting the new president, organizations such as the HRC initially tried to protect him from criticism, hoping to preserve a good relationship. After Obama's Department of Justice chose to continue the federal government's legal defense of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which prohibited Washington from recognizing same-sex marriages from states that had legalized it, McGehee and other activists planned marches and protests. But the HRC and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force were not on board. "They worried that such an event would only drain resources from other priorities," Eleveld writes. "As the ever-caustic gay Congressman Barney Frank told the Associated Press on the eve of the march, 'The only thing they're going to be putting pressure on is the grass.''Š" The newer activists accused the established groups of "living in ivory towers while they sucked up millions of dollars of the community's money without having secured any federal rights for some thirty years." They had become, Eleveld reports, "tired of waiting."

The tensions between new and established activists, between those working within the partisan system and those agitating from the outside, have relevance to political movements of all stripes. Consider the role of blogs. Gay bloggers Joe Aravosis and Joe Sudbay both had activist and legal backgrounds, and they used their knowledge to analyze and denounce the Department of Justice's initial brief defending DOMA on AMERICAblog.

The Associated Press had reported on the brief's contents, but few others seemed to be highlighting the irony of an allegedly gay-friendly administration going to bat for one of the most notorious anti-gay laws in recent memory. Only after Aravosis and Sudbay issued their angry analysis did the brief become a major source of outrage. Because experts could now weigh in without media gatekeepers, neither the administration nor its institutional-activist defenders could control the conversation.

Then there's the power of money. Eleveld documents how wealthy donors placed pressure on both the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and established gay activist groups by threatening to withhold their support. After the DOMA brief, many gay donors dropped out of a Democratic fundraiser keynoted by Vice President Joe Biden. Others stated they would just stop donating to the DNC and focus on individual candidates with more reliable track records. Money in politics turns out to be not just a tool for corporations to buy favors, but a way for individuals to hold political parties accountable to their traditional supporters. In a system of taxpayer-funded campaigns, gay activists would have lost an important tool of leverage.

Eleveld is an unabashed progressive. After leaving The Advocate, she went on to write for Equality Matters, an offshoot of the liberal group Media Matters for America. She now writes for the progressive Web outlet Daily Kos. Readers who support gay causes for libertarian reasons will surely disagree with a number of her stances. But her politics don't interfere significantly with her storytelling here, which makes sense given that it's a tale of progressives trying to influence progressives.

But there is one notable gap in Eleveld's narrative. The lengthy fight to repeal Bill Clinton's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy, which required gay troops to remain in the closet, was advanced greatly by a court case brought by a conservative gay group. In October 2010, Judge Virginia A. Phillips of the United States District Court for the Central District of California issued an injunction in Log Cabin Republicans v. United States blocking the federal government from applying the policy until the court case was resolved. This ruling helped provide leverage for the Obama administration and friendly legislators to force the regulation's elimination. While Eleveld acknowledges the ruling's importance, she rushes through the story in just half a page and provides no context of its background. Given that Obama's Department of Justice also tried to defend this policy in court, DOMA-style, the case begs to be analyzed as another example of activists applying pressure to force the administration's hand.

Don't Ask Me to Wait ends awkwardly, due to timing and perhaps the changes in Eleveld's level of access. Most of the book is framed around Obama's first term and the run-up to the 2012 election. The final chapter is titled "The Evolution," referring to the president's 2012 reversal of his opposition to gay marriage. It closes with Obama's second inaugural speech and his invocation of Stonewall alongside Selma and Seneca Falls. The Supreme Court's landmark 5–4 decision legalizing gay marriage is stuffed into the book's conclusion.

Eleveld argues persuasively that activists pushed the administration into fighting harder for gay issues than it otherwise would have done. But by ending her account by celebrating the things Obama says, she reverts to a focus on rhetoric instead of action. Obama's "evolving" position on gay marriage was a function of polling, politics, and pressure. Despite the soaring speeches, the president never was a major force for gay liberation. It was his constituency all along.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Gay Activists vs. Barack Obama."

Show Comments (0)