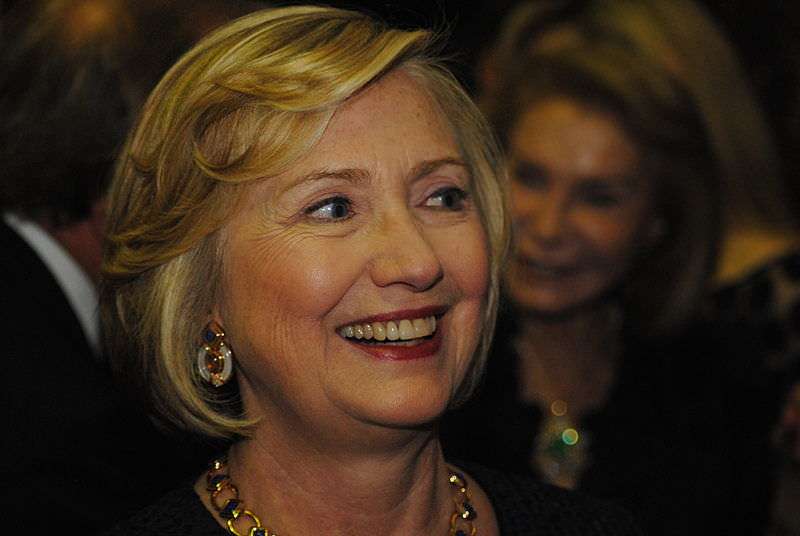

Hillary Clinton, the Unrepentant Hawk

Hillary Clinton is a long-standing and unblushing advocate of frequent military intervention abroad.

When he ran for president in 2000, George W. Bush promised to "stop extending our troops all around the world in nation-building missions." When he ran in 2008, Barack Obama trumpeted his opposition to the Iraq invasion while asserting that our "strength abroad is measured not just by armies but rather by the power of our ideals."

They didn't quite practice what they preached. But Hillary Clinton is different. She won't disappoint anyone hoping for greater restraint, because she has no use for it. The former secretary of state is a long-standing and unblushing advocate of frequent military intervention abroad.

Unlike Obama, Clinton supported the Iraq invasion. In the months before the war, she defended Bush's handling of Saddam Hussein in a way calculated to make her look presidential. "I know a little bit about what it's like on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, making these difficult decisions," she confided.

Her Iraq vote dogged her during the 2008 primaries. But as secretary of state, she proved that it had not affected her thinking. Over and over, Clinton has opted for getting into wars rather than staying out.

As a candidate, she tried to mollify anti-war Democrats on Iraq by promising to "draw up a clear, viable plan to bring our troops home starting with the first 60 days" of her administration. She may not have been sincere.

After Obama took office and began the withdrawal, Clinton lobbied to keep a sizable force there.

In Afghanistan, she favored a bigger troop surge than the one Obama eventually approved, and again, she wanted American forces to leave later rather than sooner. The earlier departure, she warned the president, "would signal we were abandoning Afghanistan," Defense Secretary Robert Gates wrote in his memoirs.

"It's not that she's quick to use force, but her basic instincts are governed more by the uses of hard power," her former State Department adviser Dennis Ross told The New York Times. But if Clinton is not "quick to use force," who is?

The civil war in Libya was just another chance to do that. While Gates was highlighting the dangers of getting pulled into the conflict, Clinton was dying to scratch her chronically itchy trigger finger. A big reason the president eventually agreed to bomb Libyan targets was that, as Gates pointed out, Clinton was pushing him so hard in that direction.

What was good enough for Libya was good enough for Syria. When an insurgency erupted there, Time magazine's Michael Crowley reports, "she teamed up with CIA Director David Petraeus to devise a plan to arm and train moderate rebel factions"—a plan similar to what John McCain was demanding. This time, though, Obama decided the risks were too great.

Anyone who thinks the only thing worse than a nuclear-armed Iran is a war with Iran will find no friend in Clinton. Going back to 2007, she has stressed the option of launching airstrikes to keep Tehran from getting the bomb. Like most in her camp, she acts as though a pre-emptive attack would be quick and easy—instead of being the opening round of a war that would not stick to her script any more than Iraq stuck to Bush's.

The Democratic Party, which nominated Obama because he represented a more prudent approach to foreign policy, apparently is happy to do a 180 with Clinton. She may relish the chance to distinguish herself from her former boss, reports The New York Times, by "presenting herself in her book and in any possible campaign as the toughest voice in the room during the great debates over war and peace." Not the wisest; the toughest.

Proving one's toughness by endorsing war is a habit of American politicians, particularly Democrats wary of being portrayed, as Obama has, as naive and vacillating. This option may be even more tempting for someone who aspires to overcome any suspicion that female politicians are weak.

But the cast of mind goes back a long time. In The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, historian Christopher Clark says that in the early 20th century, European statesmen shared "a code of behavior founded in a preference for unyielding forcefulness over the suppleness, tactical flexibility and wiliness exemplified by an earlier generation of statesmen." We know how that turned out.

Show Comments (48)