Prostitution Precrime? Monica Jones and 'Manifesting an Intent' to Prostitute in America

A woman waiting on a street corner. A woman in a tight dress. A woman who speaks to someone walking by, waves to a passing car, looks at you too long. Are there clear, unambiguous meanings to these things? Of course not—they could be the actions of someone selling sex, or of someone waiting for a ride, recognizing a friend, flirting, or engaging in thousands of other normal daily activities. Yet in cities and states around America, these actions can and are getting people arrested for "manifesting" prostitution.

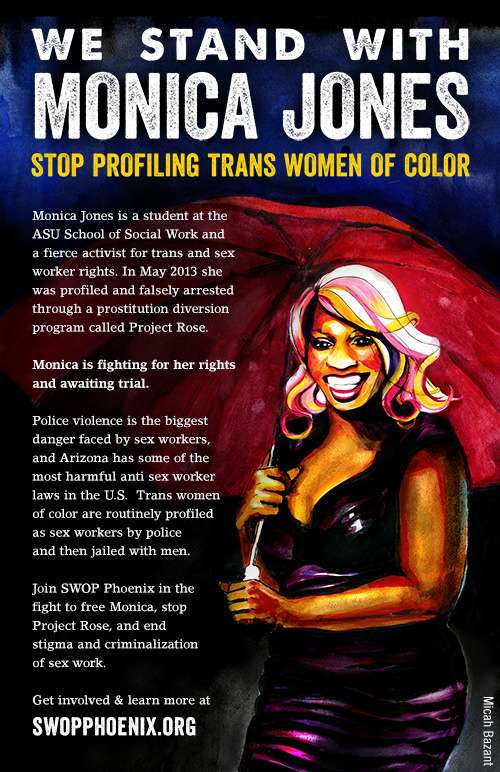

One recent case, in Phoenix, involves Monica Jones, an Arizona State University student and sex worker rights activist. Jones was arrested last year on charges of "manifesting an intent to commit or solicit an act of prostitution," a misdemeanor crime in Phoenix that carries a minimum penalty of 15 days in jail and up to six months in jail and a $2,500 fine.

In typically myopic legislative language, Phoenix Municipal Code stipulates that a person may be guilty of manifesting prostitution if he or she is "in a public place, a place open to public view or in a motor vehicle on a public roadway and manifests an intent to commit or solicit an act of prostitution." It goes on to give some examples of what this intent may look like:

the person repeatedly beckons to, stops or attempts to stop or engage passersby in conversation or repeatedly, stops or attempts to stop, motor vehicle operators by hailing, waiving [sic] of arms or any other bodily gesture; that the person inquires whether a potential patron, procurer or prostitute is a police officer or searches for articles that would identify a police officer; or that the person requests the touching or exposure of genitals or female breast.

In May 2013, Jones made the mistake of accepting a ride from an undercover officer. The officer was part of controversial city sting operation known as Project ROSE. (I wrote about the project for an upcoming issue of Reason magazine, and about the officer heading it up as part of a recent post on sex trafficking.) Jones had spoken out against the project the night before, at a local protest, as well as posted ads on Backpage.com warning sex workers about the stings.

"We believe Monica was targeted by the Phoenix police department," Jaclyn Moskal-Dairman, an activist with Phoenix's Sex Worker Outreach Project, said in a 2013 conversation with Tits and Sass blogger Caty Simon. Here's Moskal-Dairman's account of what happened with Jones:

"The evening after she spoke at the protest she was walking to a bar in her neighborhood. She accepted a ride from what turned out to be an undercover cop. He began to solicit her and she warned him he that he should be careful because of the Project ROSE stings that were going on that evening. He kept propositioning her and she asked to be let out of his vehicle. He did not let her out and actually changed lanes so she couldn't exit the car.

Jones asked if the driver was a cop, ostensibly to figure out whether she was being arrested or kidnapped. And bingo: Manifesting prostitution.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Arizona helped Jones challenge the charges, arguing in Phoenix Municipal Court on April 11 that Phoenix's law violates both the Arizona and U.S. Constitutions. "The charge against Jones should be dropped because the manifesting prostitution law … is unconstitutionally vague and overbroad," the ACLU said.

The ACLU also attested that the law infringes on free speech rights and "prohibits conduct that expresses gender identity." Jones says she was (and still frequently is) profiled for being a transgender woman of color. The cops stated that one of the first things that drew them to Jones was her "tight fitting black dress."

The Phoenix Municipal Court ruled against Jones last week. She was sentenced to 30 days in jail and a $500 fine.

The decision has sparked outrage on blogs and social media, with folks rightfully condemning the court's decision and Phoenix's prostitution laws and initiatives. But while Phoenix has one of the most broad statutes against manifesting prostitution—I've yet to see any other bans on "searches for articles that would identify a police officer"—many cities and even whole states still have similar laws on the books.

In eight states—North Carolina, California, Kentucky, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Hawaii, Ohio, and Minnesota—it's illegal to "loiter for the purpose of engaging in prostitution offense." This basically seems to mean "look to cops like a prostitute" in a public space.

Additionally, a number of cities prohibit loitering or manifesting for prostitution purposes. In Arlington, Texas, "engag(ing) in conversation with persons passing by" could get your arrested, and Dallas has a similar law (in 2013, one woman was arrested there or being "engaged in conversation in a high-prostitution area" with a man in a truck). In Portland, Oregon, "lingering in or near any street or public place" or "circling an area in a motor vehicle" suspiciously could be a crime.

New York City, of course, has laws against loitering like a prostitute—which Kate Mogulescu, a supervising attorney with the Legal Aid Society, has described as both arbitrary and discriminatory in their enforcement. In 2010, Mogulescu fought (and won) a conviction charge for a transgender woman picked up after talking to a taxi driver. "These arrests are… set up to be immune from scrutiny and, traditionally, they've been unchallenged," Mogulescu said.

Occasionally, these cases do reach the courts, with mixed results. Among the wins for the state: a 1980 case challenging a Milwaukee loitering for prostitution law; a 1985 case challenging North Carolina's statute; and a 1986 case out of Kansas City.

But judges have long been ruling such statutes unconstitutional, as well. The Supreme Court of Alaska did so back in 1978 (Brown v. Municipality of Anchorage), calling the city of Anchorage's ban on loitering for the purposes of prostitution "unconstitutionally vague." The Supreme Court of Nevada ruled similarly in 2006.

An Oklahoma judge struck down a Tulsa loitering for prostitution law in 1980 (Profit v. City of Tulsa), writing that "a person should be convicted only for what he does, not for what he is." In a 1983 decision, Judge J.J. Rossman of the Oregon Court of Appeals overturned a loitering for prostitution conviction, noting that "it is not a violation of the law merely to look like a prostitute might."

A decade later, Florida's Supreme Court found the city of Tampa's ordinance prohibiting loitering for prostitution to be unconstitutional. The court noted that it left too much up to "officers' discretion" while "implicat [ing] protected freedoms" such as "talking and waving to other people."

Yet history repeats itself: The Florida court system found itself ruling on pretty much the same thing in 2013 (West Palm Beach v. Chatman). Florida's Fourth District Court of Appeals ended up overturning a West Palm Beach ordinance, after a trans woman waiting for a ride in a "known prostitution area" was arrested.

It seems pretty clear that these laws do criminalize people merely for "look(ing) like a prostitute might," whether this determination is based on race, gender identity, or class markers. As a relatively unremarkable looking and dressing white woman, I could probably wave and holler to all the passing cars I wanted without fear. Cops are going to be more likely to assume certain invidividuals "intend to commit prostitution" and, because these laws against manifesting it are so vague, they don't have to look far to confirm their biases. Once you're suspected of being a sex worker, any manner of ordinary actions become not just probable cause but criminal behavior.

"Even assuming the government has a compelling interest in prohibiting prostitution, a measure that criminalizes a broad range of legal speech surely cannot be the 'least restrictive' means to furthering such an interest," the ACLU wrote in a memo supporting Jones' acquittal. It surely can't be—and if the law was targeting "regular" folks, there would probably be more of an uproar. But these are sex workers and trans women and other marginalized individuals we're talking about. In Arizona and many other parts of the country, restricting their freedom and rights is simply seen as good police work.

Show Comments (50)