The Bipartisan Commission Ruse

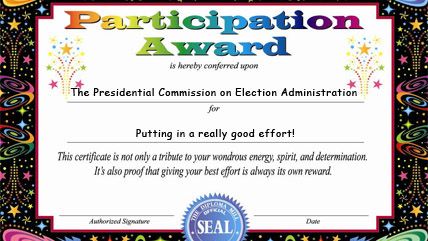

These panels are the equivalent of the participation awards handed out to every kid in little league.

In the polarized atmosphere of Washington, there is one thing that both parties can usually agree on: convening independent, bipartisan panels of respected experts to devise solutions to tough problems. Actually, there's one more thing they can usually agree on: ignoring what those groups recommend.

Blue-ribbon panels were much in the news this past week. The Presidential Commission on Election Administration came out with a report making the case for expanding early voting options, allowing online voter registration and eliminating long lines at the polls. The little-known Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board issued an analysis concluding that the National Security Agency's domestic phone records surveillance program is illegal and ineffectual.

Know what else is ineffectual? Recommendations from groups like these.

Perhaps the most famous is the 2010 National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, known as Simpson-Bowles. It is habitually celebrated by Republicans and Democrats, who have somehow managed to avoid enacting most of the measures it proposed.

Likewise, the 2006 Iraq Study Group got positive reviews when it called for a phased withdrawal of U.S. forces from the country. But in the nation's capital, positive reviews pack all the firepower of a T-shirt cannon. President George W. Bush did pretty much the opposite of what the study group proposed.

The lesson of these boards is that if they endorse what the crucial players in Washington already want to do, their proposals will come into being, and if not, they won't. But we could cut out the middleman and ask Congress and let our leaders adopt their preferred policy without waiting for recommendations they could predict in advance.

The privacy board was particularly superfluous, because it was re-plowing ground freshly tilled by President Barack Obama's Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies. That group also urged major changes in the NSA programs. Obama responded by accepting a few of the ideas, rejecting others and generally doing his best to please everyone.

Even his acceptances were hedged. One key proposal was to require NSA to get judicial approval to gain access to the database. But the president made only a vague commitment to allow records "to be queried only after a judicial finding or in the case of a true emergency." And the White House press office assures me this commitment applies only during a 60-day "transition period," with no promise it will be permanent.

The privacy board's conclusions are likely to have even less effect on policy. This group believes the mass collection of phone data is illegal under federal law? It uncovered not "a single instance involving a threat to the United States in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation"?

So what? If a bunch of experts say one thing and the spies say the opposite, you can expect the president to side with the spooks a lot more often than not.

A similar problem exists with respect to the elections panel, which obviously did its best to decide what changes would be fair, reasonable and good for democracy. But we need this group to tell us all that like we need it to tell us when the sun is shining. The knowledge is present. What is absent among many elected representatives is the desire to act on it.

The decision of many states to reduce voting opportunities and reject electronic registration was not an act of carelessness or ignorance. It was typically part of a deliberate Republican strategy to curb the voting strength of racial minorities, poor people, immigrants and students -- in other words, people who have the regrettable tendency to vote Democratic. Noble ideals are no match for political self-interest.

That's why setting up independent bodies to assess the evidence and reach rational conclusions about policy is usually a waste of time and effort. The documents are a glorious feast for editorial writers but a bowl of day-old dog food to the people who make policy. As a rule, the function of the panels is either to delay action on issues lawmakers want to duck or to provide a harmless outlet for the critics of policies that are set in stone.

Ultimately, they're the equivalent of those participation trophies handed out to every kid who plays in a sports league. They look nice on the shelf, but you can't take them seriously.

Show Comments (18)