When Cops Don't Need a Warrant To Crash Through Your Door

"Exigent circumstances" provide a multi-purpose end-run around the Fourth Amendment

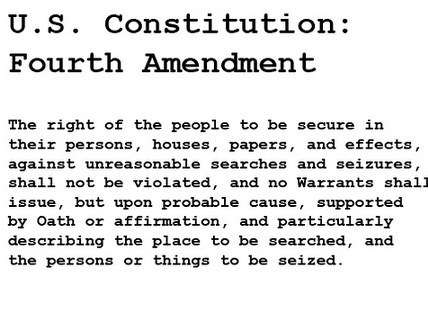

The Fourth Amendment protects us from random invasions of our homes by police, right? We know we're secure in our "persons, houses, papers, and effects" unless the cops demonstrate probable cause to a judge and get a warrant. Except… Except when they don't. The fact of the matter is that police have a lot of leeway to bust your door down and take a look around if they fear that waiting for a warrant could lead to loss of evidence or danger to people. Or lead to something, anyway. That end run around the Fourth Amendment is called "exigent circumstances," and nobody really seems to be sure where it starts and stops. Except for the police. They know it when they see it.

On July 17, a law enforcement task force including federal and local officers barged into the Sarasota, Florida home of Louise Goldsberry after a brief standoff. The officers, looking for a suspected child molester in Goldsberry's apartment complex, insisted that the nurse's frightened reaction to the sight of a stranger pointing a gun through her kitchen window was all the reason they needed to assume their target's presence. "I feel bad for her," U.S. Marshal Matt Wiggins told Sarasota Herald-Tribune columnist Tom Lyons. "But at the same time, I had to reasonably believe the bad guy was in her house based on what they were doing."

What Goldberry and her boyfriend were doing was cowering in the presence of armed invaders. But that really might be all that it takes.

The problem lies in the definition of exigent circumstances — or, rather, the lack thereof. An unsigned article on the subject in the Alameda County, California, District Attorney's office journal, Point of View explained:

[S]trangely, the courts have been unable to provide officers with a useful definition of the term "exigent circumstances." Probably the most honest definition comes from the Seventh Circuit which said that "exigent circumstances" is merely "legal jargon" for "emergency," explaining that lawyers employ the more grandiose terminology "because our profession disdains plain speech."

The article goes on to explain, "Not only is the definition of the term elusive, the number of situations that are deemed 'exigent' keeps expanding." Where once exigent circumstances required a threat to public safety, they expanded to encompass the potential for a subject to escape, or just to dispose of evidence by, for example, flushing drugs down the toilet. Exigent circumstances now also include a new and looser category of situations involving "community caretaking" which, at least theoretically, justify some kind of immediate action, including kicking in doors without warrants.

Does the Supreme Court provide any guidence? Well…some. Said the court in 2006's Brigham City v. Stuart, following on a string of similar rulings, an entry and search is justified if it is "objectively reasonable" under the circumstances, that reasonableness being determined by public concerns outweighing the intrusiveness of police barging in. In that case, police entered a backyard after spotting juveniles drinking beer and and then walked into a private home after seeing a fight in progress through a window. The court ruled the entry and subsequent arrests justified. There's no check list to follow in making that call, leaving the decision to the officers on the scene. As the author of the Point of View article concedes, "Because of these developments, the term 'exigent circumstances' has become a bloated and almost meaningless abstraction."

But in the Sarasota case, the exigent circumstances were created by the police themselves. Louise Goldsberry screamed and cowered because a police officer pointed a gun at her through her own kitchen window. Marshal Wiggins and company used the fact that they'd scared the hell out of Goldsberry as the justification for entering and searching her home. That can't be OK, can it?

As it turns out, it just might be. The U.S. Supreme Court addressed the issue of police-created exigencies in the 2010 case of Kentucky v. King, involving police entry into an apartment after they heard movement in response to their knock on the door. The sounds, the officers insisted, could have been made by the suspects destroying evidence. Justice Samuel Alito wrote for the majority, "The exigent circumstances rule applies when the police do not create the exigency by engaging or threatening to engage in conduct that violates the Fourth Amendment."

After the King decision, the FBI posted guidance on its Website about when and how police officers could conduct searches in response to circumstances of their own making.

In holding that the exigent circumstances exception applies as long as the police do not gain entry to premises by means of an actual or threatened violation of the Fourth Amendment, the Court eliminated the confusion inherent in the tests used by the lower courts. The rule announced by the Court clearly allows officers confronted with circumstances, such as those present in King, to take appropriate steps to resolve the emergency situation. However, officers must be mindful of the fact that they cannot demand entry or threaten to break down the door to a home if they do not have independent legal authority for doing so. According to the Court, to do so would constitute an actual or threatened violation of the Fourth Amendment and, thereby, deprive the officers of the ability to rely upon the exigent circumstances exception.

No threat to illegally crash through the door, no foul.

Pointing a gun through a window might constitute a heart-stopping threat to life and limb, but not necessarily to protections against unreasonable search and seizure. In a world of loosely interpreted reasonableness under the circumstances, it could pass court scrutiny.

Unfortunately, "could" and "might" are likely as close as we can get to knowing if a rush of police officers through a door makes the legal cut, short of judicial scrutiny in a given case. Police on the scene are empowered to use their own judgment as to whether an "emergency," defined ever-more loosely as time goes on, exists that justifies forcing an entry into private property in the absence of a warrant.

Fourth Amendment notwithstanding, we really do live in a world where screaming when an unidentifiable police officer points a gun at you through your window may be all it takes to authorize knocking your door off its hinges and dragging you outside in handcuffs.

Show Comments (71)