If Eric Holder Lied to Congress, He Shouldn't Be Immune to Consequences

Isn't the Attorney General bound by the same laws to tell the truth as the rest of us are?

The firestorm commenced by the revelation of the execution of a search warrant on the personal email server of my Fox News colleague James Rosen continues to rage, and the conflagration engulfing the First Amendment continues to burn; and it is the Department of Justice itself that is fanning the flames.

As we know from recent headlines, in the spring of 2010, the DOJ submitted an affidavit to a federal judge in Washington, D.C., in which an FBI agent swore under oath that Rosen was involved in a criminal conspiracy to release classified materials, and in the course of that conspiracy, he aided and abetted a State Department vendor in actually releasing them. The precise behavior that the FBI and the DOJ claimed was criminal was Rosen's use of "flattery" and his appeals to the "vanity" of Stephen Wen-Ho Kim, the vendor who had a security clearance. The affidavit persuaded the judge to issue a search warrant for Rosen's personal email accounts that the feds had sought.

The government's theory of the case was that the wording of Rosen's questions to Kim facilitated Kim's release of classified materials, and Rosen therefore bore some of the criminal liability for Kim's answers to Rosen's questions. Kim has since been indicted for the release of classified information (presumably to Rosen), a charge that he vigorously denies. Rosen has not been charged, and the DOJ has said it does not intend to do so.

The government knew that Rosen committed no crime -- not as a conspirator nor as an aider and abettor -- by asking Kim for his opinion on the likely North Korean response to the then-pending U.N. condemnations of North Korea's nuclear and ballistic missile tests. By telling a federal judge, however, that Rosen somehow was criminally complicit in the release of classified information by the manner in which he put questions to Kim, the DOJ substantially misled the judge into signing a search warrant, which, when executed, would enable the feds to read Rosen's private emails. Then, by reading them the feds were led to Fox News telephone numbers in New York City and in Washington, which they since have acknowledged they have monitored.

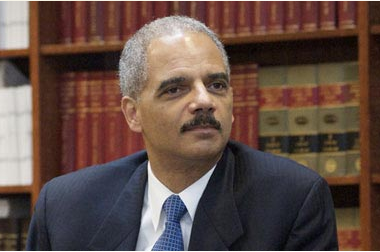

When asked at a congressional hearing just two weeks ago on May 15 to address this, Attorney General Eric Holder replied: "With regard to the potential prosecution of the press for the disclosure of material, that is not something that I have ever been involved in, heard of or would think would be a wise policy."

Whether under oath or not, because Holder spoke in his official capacity before a congressional committee in its official capacity, he was legally bound to tell the truth and legally bound not to mislead the committee. Last Thursday, President Obama in a speech on national security stated, "Journalists should not be at legal risk for doing their jobs. Our focus must be on those who break the law." The next day, the DOJ leaked to NBC News the inconvenient truth that Holder had personally authorized seeking the search warrant for Rosen's personal emails; and over the long holiday weekend, the DOJ confirmed that.

What's going on here? Isn't the Attorney General bound by the same laws to tell the truth as the rest of us are? Doesn't the First Amendment protect from criminal prosecution and government harassment those who ask questions in pursuit of the truth?

The answers to these questions are obvious and well grounded. One of Holder's predecessors, Nixon administration Attorney General John Mitchell, went to federal prison after he was convicted of lying to Congress. The same Attorney General who told Congress he had "not been involved" in the Rosen search warrant before the DOJ he runs revealed that he not only was involved, he personally approved the decision to seek the search warrant, must know that the Supreme Court ruled that reporters have an absolute right to ask any questions they want of any source they can find. The same case held that they cannot be punished or harassed because the government doesn't like the answers given to their questions. And the same case held that the if answers concern a matter in which the public is likely to have a material interest, they can legally be published, even if they contain state secrets.

The whole purpose of the First Amendment is to permit open, wide, robust, even unfettered debate about the government. That debate cannot he held in an environment in which reporters can be surveilled by the government because of their flattery. And the government cannot serve the people it was elected to serve when its high-ranking officials can lie to or mislead the congressional committees before which they have given testimony.

The great baseball pitcher Roger Clemens spent a few million dollars successfully defending himself against charges brought by Holder's DOJ, which accused him of doing what Holder himself has arguably done. Is this what you expect from the government in a free society? And when reporters clam up because they don't like the feds breathing down their necks when they reveal inconvenient -- or even innocuous -- truths about the government, don't we all suffer in our ignorance?

Show Comments (27)