The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Libel by Implication: When Is Half the Truth a Falsehood?

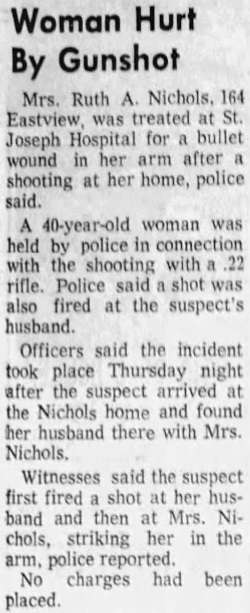

The Alexis Wilkins' (FBI Director's Girlfriend's) Libel by Implication Suit Can Go Forward post reminded me of one of my favorite cases, Memphis Pub. Co. v. Nichols (Tenn. 1978). The Memphis Press-Scimitar (what a great newspaper name) published the following article that mentioned Mrs. Ruth Ann Nichols:

Please think briefly about the story, and then click on the MORE link below to learn what the court decided.

Did you read the story as suggesting that the shooter found her husband in a compromising position with Mrs. Nichols—perhaps having sex, or having had sex, or being just about to have sex? That's apparently how many readers read the story as well.

But it turns out that, though each statement in the story was literally true, Mrs. Nichols was at the Nichols home together with the shooter's husband, Mr. Nichols, and two neighbors. They were apparently all sitting in the living room, talking.

The court concluded that the story could be libelous—assuming negligence was shown on the newspaper's part—because, even though the statements were literally true, they carried a strong implication (that the husband and Mrs. Nichols were together by themselves in a compromising position) that was false:

In our opinion, the defendant's reliance on the truth of the facts stated in the article in question is misplaced. The proper question is whether the meaning reasonably conveyed by the published words is defamatory, "whether the libel as published would have a different effect on the mind of the reader from that which the pleaded truth would have produced."

The publication of the complete facts could not conceivably have led the reader to conclude that Mrs. Nichols and Mr. Newton had an adulterous relationship. The published statement, therefore, so distorted the truth as to make the entire article false and defamatory. It is no defense whatever that individual statements within the article were literally true. Truth is available as an absolute defense only when the defamatory meaning conveyed by the words is true.

Such "defamation by half-truth" decisions are rare. All statements, after all, omit something, and one can always argue that the full story would convey a somewhat different message from the partial story. Usually that's not enough to turn literal truth into libel. But in some situations, where the statement does carry a very strong implication that turns out to be false, a libel claim can indeed be brought even when the statement is literally true.

Another classic example—though just a hypothetical and not a real case—involves the first mate who, upset by his teetotaling captain, writes in the ship's log,

Captain sober today.

The statement may be literally accurate (the captain was sober today, as on all days) but it carries a very strong implication that turns out to be false (that today was unusual in this respect).

H.P. Grice's work on conversational implicatures, by the way, relates to this.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Your point is taken. Shaping "news" to fit an agenda has been normal since news was invented. The full truth is also never known, because the story never ends, right ?

In this case, the newspaper is faulty and acts contrary to the purpose of truthfully informing the public, which is never the point of the press, for they are there to make money and not report truth. Same is true for legal disputes - the hell with truth, just win your case.

Truth is painful as likewise boring too. Spice it up and make a buck - see you in court.

If I were on the jury, I'd want to see some evidence that this was a habit of the paper, and not merely an accident of editing.

Evidence of malice and not merely mistake, yes. Requiring it to be habit, no. A one-time malicious act is still wrong.

What happened to the unnamed shooter?

Grammar also counts.

Consider the difference between

Let's eat, grandma.

and

Let's eat grandma.

The sober all day quote may be apocryphal, but there is a longer version in David Hackett Fischer's Historian's Fallacies. pg 272

Another example is provided by a historian of Salem, Massachusetts, who writes that

Captain L--had a first mate who was at times addicted to the use of strong drink, and occasionally, as the slang has it, "got full." The ship was lying in a port in China, and the mate had been on shore and had there indulged rather freely in some of the vile compounds common in Chinese ports. He came on board, "drunk as a lord," and thought he had a mortgage on the whole world. The captain, who rarely ever touched liquors himself, was greatly disturbed by the disgraceful conduct of his officer, particularly

as the crew had all observed his condition. One of the duties of the first officer [i.e., the mate] is to write up the "log" each day, but as that worthy was not able to do it, the captain made the proper entry, but added : "The mate was drunk all day." The ship left port the next day and the mate got "sobered off." He attended to his writing at the proper time, but was appalled when he saw what the captain had done. He went on deck, and soon

after the following colloquy took place :

"Cap'n, why did you write in the log yesterday that I was drunk all day?"

"It was true, wasn't it?"

"Yes, but what will the owners say if they see it? T will hurt me with

them."

But the mate could get nothing more from the captain than "It was

true, wasn't it?

The next day, when the captain was examining the book, he found at the bottom of the mate's entry of observation, course, winds, and tides :

"The captain was sober all day."10

10. Charles E. Trow, The Old Shipmasters of Salem ( New York, 1905 ) , pp. 14- 15 .