The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

What We Learned From Jodi Kantor's Latest Expose About The SCOTUS NDA

The Chief is now requiring all employees (but likely not the Justices) to sign Non-Disclosure Agreements, which do not seem to be working.

In September 2024, Jodi Kantor published a stunning set of leaks concerning Trump v. United States. At the time, I wrote that the Trump leaks were "far worse than the Dobbs leak." Apparently, Chief Justice Roberts was also bothered.

Two months later, according to Kantor's latest report, Roberts required all Court employees (but apparently not the Justices) to sign non-disclosure agreements. Indeed, this mandate came almost halfway into the clerkship. It is customary to require employees to sign NDAs before they learn confidential information, but the Chief switched course midstream. Presumably, the things learned before signing that document were not covered by the agreement.

This piece is the latest in Kantor's string of articles about inside Court deliberations. Her past installments came in December 2023 about Dobbs, June 2024 about Bruen, September 2024 about Trump immunity, December 2024 about SCOTUS ethics, June 2025 about Justice Barrett, and November 2025 about the liberal Justices. As the dates reveal, Kantor has continued to publish articles after the NDAs were signed, so they do not see to have been entirely effective--unless the people causing the leaks were not subject to the NDA. As Kantor said in a recent interview, she is watching them. Query whether the NDA prohibited the disclosure of the existence of the NDA? At least the Chief is trying something.

Let's walk through what we learned.

First, Kantor alludes to her sourcing:

Its employees have long been expected to stay silent about what they witness behind the scenes. But starting that autumn, in a move that has not been previously reported, the chief justice converted what was once a norm into a formal contract, according to five people familiar with the shift.

Five people is a very precise number. It is not clear if these people were subject to the NDA, or were even employees at the Court. This could be five people who learned of the NDAs second-hand. Of course, by using intermediaries, the leakers limit potential liability under the NDA.

Second, we learn about the timing of the NDAs.

Roberts summoned "employees" to an all-hands meeting in the grand conference room. Perhaps standing up the portrait of Chief Justice Marshall, Roberts asked the gathered employees to sign an NDA. I suspects this included all of the clerks. Did Roberts give any notice they would have to sign? Did they have to sign on the spot? If they declined to sign, were they terminated? Could they consult counsel? So many questions.

In September 2024, The Times published an article describing how the chief justice pushed to grant President Trump broad immunity from prosecution. The article quoted from confidential memos by the chief justice and other members of the court who applauded his reasoning. Weeks later, the chief justice abruptly introduced the nondisclosure agreements, after the term had begun.

In November of 2024, two weeks after voters returned President Donald Trump to office, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. summoned employees of the U.S. Supreme Court for an unusual announcement. Facing them in a grand conference room beneath ornate chandeliers, he requested they each sign a nondisclosure agreement promising to keep the court's inner workings secret.

The 2024 election was held on November 5. Two weeks later would have been the week of November 18. The Court released orders on November 18 (no grants), and held a conference on November 22. If I had to guess, this gathering was held late Friday afternoon after the conference, right before the holiday. Did Roberts ask his colleague to vote on whether to require NDAs? Does the Rule of 5 apply here, or did the vote have to be unanimous? Or did Roberts simply tell his colleagues what was coming? What a nice way to begin Thanksgiving break.

This is the sort of practice that employment lawyers detest: forcing employees to sign onerous agreements without any time to consider it--especially right before a major holiday. During the Dobbs investigation, Joan Biskupic reported that clerks were ordered to turn over their phones. Apparently the conservative clerks gladly handed over their devices while some of the liberal clerks lawyered up. Did all of the clerks actually sign the NDA, five months into their employment? If they declined, would they be fired? Would the Chief even have the power to fire someone else's law clerk?

Third, we do not learn much about the contents of the NDA:

The New York Times has not reviewed the new agreements. But people familiar with them said they appeared to be more forceful and understood them to threaten legal action if an employee revealed confidential information. Clerks and members of the court's support staff signed them in 2024, and new arrivals have continued to do so, the people said.

Who drafted the NDA? Did the Court do it in-house, or did they retain outside counsel? The policy was prepared "abruptly" so I doubt there was much time to seek counsel. If it was drafted in-house, what experiences does the Chief's counsel have with a government-employee NDA--especially where the information is not classified? Maybe they used LegalZoom or asked ChatGPT? So many questions.

The problem of course is the Barbara Streisand effect. By enforcing an NDA, the Court will be forced to publicize the very confidential information it seeks to protect. At most, this policy will have an in terrorem effect, and perhaps increase the potential costs of leaking. After all, I'm sure some future Jack Smith, inspired by Jean Valjean, joined by the merry band of innovative lawyers in the Public Integrity Section, could transform the breach of an NDA into some federal criminal offense. This sort of trickery would otherwise be unanimously rejected by the Supreme Court, but I see nine recusals.

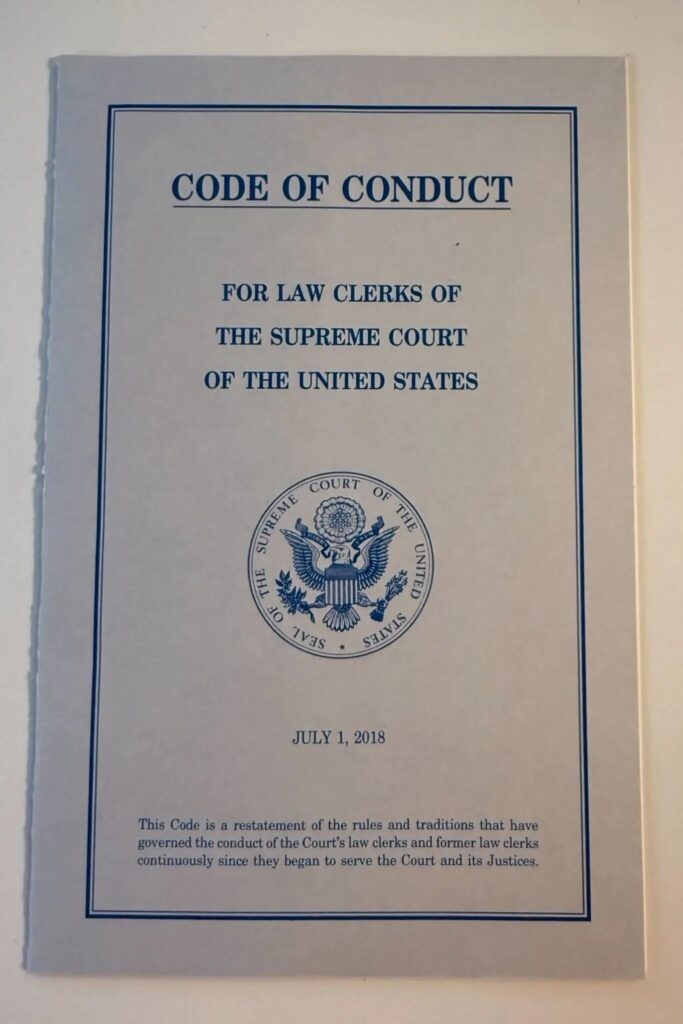

Fourth, Kantor obtained a print copy of the "Code of Conduct for Law Clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States." I don't think the existence of this document has ever been confirmed. The booklet is dated, July 1, 2018. I don't know if the book is printed annually at the start of each clerkship cohort, or if this document had been in effect for some time. I would have to guess the document was updated after the Dobbs leak, so perhaps a clerk from the OT 2018 class gave it to the NY Times. You know who you are.

At the bottom of the cover is a curious note:

This Code is a restatement of the rules and traditions that have governed the conduct of the Court's law clerks and former law clerks continuously since they began to serve the Court and its Justices.

The Code is like the common law: it has always been in effect, yet always changes.

Kantor quotes from part of the booklet:

"The law clerk owes the appointing Justice, all other Justices, and the Court as an institution, duties of complete confidentiality, accuracy and loyalty," instructed a 2018 version obtained by The Times, in which every page is labeled "confidential — for authorized internal use only." The final page mentioned that breaches could lead to "appropriate sanctions," but did not specify what those might be.

I doubt this handbook had any impact on the clerks' behavior. If it did, the Chief would not have needed to level up with NDAs.

Fifth, Kantor explains that the NDAs may affect law clerks who seek to collect massive bonuses:

The agreements may complicate another Supreme Court tradition: former clerks cashing in on what they learn there. Law firms now pay clerks signing bonuses as high as $500,000. The court requires them to avoid working on its own cases for two years. But after that, former clerks often spend the rest of their careers monetizing the knowledge they gained from working directly with the justices and also reading still-secret older case files, some said in interviews. While they are not supposed to share specifics with clients, plenty of details slip out, the former clerks said.

I am intrigued about how clerks share information from "still-secret older case files" with clients. I had never thought about it, but I suppose clerks may keep some documents from their clerkships on the way out. (Back when I clerked, there was no VPN, so I stored files on my personal computer so I could work from home.) Would old SCOTUS documents still be valuable to clients? I suppose. But I am struggling to see this point. Then again "some," meaning several clerks said this in interviews, so the practice must be common. I suppose there is a reason firms pay a $500,000 signing bonus for SCOTUS clerks who are barred from working before the Court for two years.

Finally, speaking of the Dobbs leak investigation, there is a nugget that I hadn't seen reproted before:

The court conducted an investigation of its staff but mostly spared the justices, and the source was never publicly identified.

The Justices were "mostly" spared? So they were investigated to some degree? I need to know more.

I'll have more to say about the NDA in a future column.

Show Comments (13)