The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

N.Y. Synagogue Allowed to Fire Teacher for Anti-Zionist Blog Post

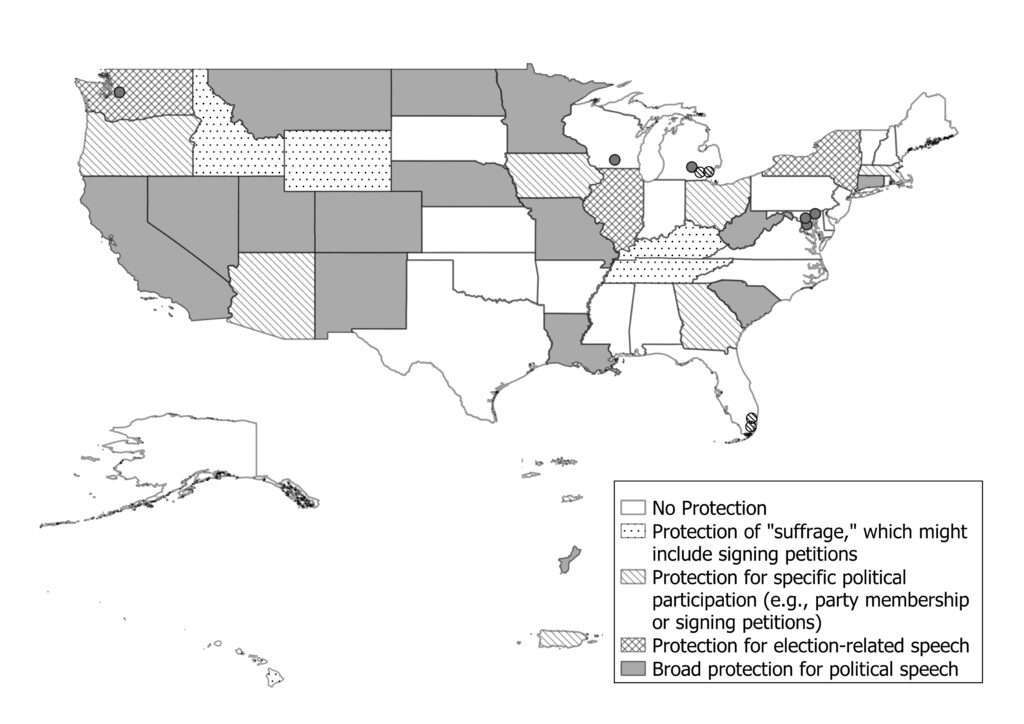

[1.] The First Amendment applies only to the government, and thus doesn't limit private employers from firing employees based on their speech. But many states have statutes that do impose such limitations, as the map above suggests. (For more on this, see my Private Employees' Speech and Political Activity: Statutory Protection Against Employer Retaliation and Should the Law Limit Private-Employer-Imposed Speech Restrictions? articles.)

Some of these statutes broadly protect a wide range of employee speech. Others protect particular forms of election-related activity: New York, for instance, bans employers from firing employees for campaigning for a candidate or raising funds for a candidate, party, or political advocacy group.

But New York also bans employers from firing employees for off-the-job "legal recreational activities," defined as

any lawful, leisure-time activity, for which the employee receives no compensation and which is generally engaged in for recreational purposes, including but not limited to sports, games, hobbies, exercise, reading and the viewing of television, movies and similar material.

There is also an exception for activity that "creates a material conflict of interest related to the employer's trade secrets, proprietary information or other proprietary or business interest."

Does blogging, Tweeting, etc. qualify as "recreational activities," much as "reading and the viewing of television, movies and similar material" qualifies? In yesterday's Sander v. Westchester Reform Temple, the N.Y. high court (in a majority opinion by Judge Caitlin Halligan for five of the seven judges) notes the issue but doesn't resolve it:

[The definition of recreational activities] sweeps broadly on its face …. The term "hobbies" has an expansive dictionary definition[, …] "a pursuit outside one's regular occupation engaged in especially for relaxation" …. Plaintiff argues that some hobbies surely have an expressive component and communicate content, and that reading or viewing media entails the selection of content as well. {We reserve this question of statutory interpretation for another day ….}

A solo concurrence by Judge Shirley Troutman, on the other hand, endorses the view of the intermediate appellate court in this case, which held that even if firing someone for blogging (or presumably for Tweeting or something similar) would be illegal firing for recreational activity, firing someone for the content of their blog post wasn't covered by the statute.

And a solo concurrence by Judge Jenny Rivera suggested a different approach:

Blogging—writing about one's observations, experiences, or areas of interest on an online platform—can be a recreational activity depending on the blogger's intended purpose…. [D]epending on the blog's content, uncompensated blogging may be a recreational activity, such as blogging about a recent vacation or the best local vegan eateries. These examples describe leisure-time musings—akin to "hobbies," a protected recreational activity under Labor Law § 201–d(1)(b). As the majority notes, "[t]he term 'hobbies' has an expansive dictionary definition." Further, plaintiff rightly argues that some hobbies surely have an expressive component and communicate content. Thus, there is support for interpreting blogging as a hobby or as a sufficiently similar activity to be of "like kind."

By contrast, other types of blog content may intend to provoke strong emotional responses in a manner disassociated from any leisurely endeavor of the writer. For example, blogging the writer's viewpoint to encourage others to take political action may not have a recreational purpose or be relaxing, fun, or entertaining; rather, it may be a convenient method for the writer to disseminate a message motivated by a sense of societal duty and responsibility.

Plaintiff's blogging is no doubt her physical act of posting her thoughts on a certain topic on her website. However, whether plaintiff's blogging can be characterized as a recreational activity based on its content is not as clear.

The law in New York about whether private employers may fire employees for the content of their blog posts, Tweets, and the like is thus unsettled. On the other hand, the lower court decision seemed to help settle the matter against substantial protection for off-the-job speech (outside the narrow protection clearly provided by the separate election-related political activity provision). By reversing the lower court decision, which read the recreational activity statute as essentially allowing such firing, the New York court has opened the door to at least some extent to lawyers' raising such claims.

[2.] This case, however, didn't involve just any private employer and private employee: It involved a synagogue (the Westchester Reform Temple) firing a teacher whose teaching included some religious subjects. The Supreme Court has held, in Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru (2019) and Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. EEOC (2012), that religious institutions have a First Amendment right to select such teachers—alongside clergy and other employees who had important religious duties—without regard to antidiscrimination laws. Under this so-called "ministerial exception," they could, for instance, discriminate based on race, sex, age, disability, and the like. And, unsurprisingly, the majority in this case concluded that they could also discriminate based on recreational activities (and presumably political activities):

Plaintiff's "core responsibilities as [a] teacher[ ] of religion" are similar to those in Hosanna–Tabor and Our Lady of Guadalupe. She was responsible for teaching religious texts through one-on-one study and weekly Torah portions, as well as planning and attending religious programming. Those duties leave little doubt that she was charged with "educating young people in their faith." ….

[3.] But the case didn't just involve a synagogue and a teacher; it also involved a teacher whose posts were anti-Zionist:

The blog post said, among other things, that the authors felt compelled to "speak out against israel's [sic] most recent attack on Gaza" and "reject[ed] the notion that Zionism is a value of Judaism." Plaintiff alleges that she and the Rabbi discussed the meaning of Zionism, and she assured him that she respected the Temple's position and would not share her views on the job. Plaintiff also alleges that the Rabbi subsequently expressed complete confidence in her teaching abilities. Nonetheless, Plaintiff was fired less than a week later….

And Judge Rivera's solo concurrence focused on that; she concluded that she needn't decide whether recreational activity generally covers political blogging, or whether the ministerial exception covered schoolteachers like plaintiff. Rather, she concluded that plaintiff's activity was excluded by the "material conflict of interest" exception in the statute—a conclusion that would apply far beyond just religious employers. She acknowledged that,

As a general matter, conflicts of interest in the employment setting confer some benefit on the employee or a competitor at the expense of the employer's business interests.

But she concluded, based on her reading of the statutory text, legislative history, and lower court caselaw that in this statute "conflict of interest" covered activity that affects "how the business is perceived within the relevant community and whether the employee's activity places the business and its mission in a negative light":

The statute … reflects the Legislature's intention to "strike the difficult balance between the right to privacy in relation to the non-working hours activities of individuals and the right of employers to regulate behavior which has an impact on the employee's performance or on the employer's business." … For example, in Thomas v. Smith (S.D.N.Y. 2008), the plaintiff—whose public employer provided services to both victims and perpetrators of sexual assault—alleged she was fired because she made comments at a community forum advocating the castration of sex offenders….The court found that the plaintiff's statements materially conflicted with the employer's business interests because her "public support of castration as a means for punishing sex offenders offended [the employer]'s methods and philosophy, and exposed [the employer] to unfavorable attention in the local press." …

Similarly, in Berg v. German Nat. Tourist Off. (N.Y. App. Div. 1998), the [New York intermediate appellate court] interpreted the "material conflict of interest" provision as allowing the German National Tourist Office to terminate an employee after learning that they were a translator of Holocaust revisionist articles. Although the court concluded without explanation that the exception applied, given the nature of the translated articles and the Holocaust's historical connection to Nazi Germany, it is evident that plaintiff's off-duty activity could invite a public backlash against the employer, thereby constituting "a material conflict of interest" between the employee and the German National Tourist Office's "business interest." …

Plaintiff espoused a viewpoint (i.e. anti-Zionism) at odds with her employer's "philosophy" (i.e. Zionism) and its mission. Thus, as the Temple asserts, plaintiff's publicly posted assertions and opinions directly undermine the Temple's business interest as a synagogue, as some congregants may view Zionism as a feature of their religious or ethnic identities as Jews.

Additionally, Sander's presence as a Jewish educator of children could invite a backlash among at least some of her students' parents due to her anti-Zionist views. If the Temple were to lose membership en masse, its proprietary or business interests—even as a nonprofit—would inevitably suffer….

So, under this view, blogging that is sufficiently unpopular, at least among the employer's clientele, is unprotected by the statute, even if blogging that is more popular or less controversial.

My general view is that the majority got it right on point 2: Religious institutions have a First Amendment right to choose their teachers of religion, including based on the teachers' off-duty speech (as well as their race, sex, etc.). As to points 1 and 3, I'm inclined to read recreational activity broadly enough to include public commentary (as on a blog or in tweets), and I'm inclined to read conflicts of interest more narrowly, to include just traditional conflicts such as working for a competitor. But these are difficult questions of how to interpret this state statute, and my views on that subject are quite tentative.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

It seems like the exception in the statute for a "conflict of interest" basically guts the rule.

I don't see how. The law just wasn't well-thought-out with regard to religious employers, which are a tiny fraction of employers. I think this came out right. This law is generally to protect people who go hunting on weekends or do weird sex stuff or whatever from employers who find that distasteful, and AFAIK it works fine.

Because the statute reads to also exempt if there's a "business interest." An employer will always be able to plausibly claim that the "political activities" or "recreational activities" somehow conflict with their business, especially in the age of social media where people can shame easily "X company is employing Fred Johnson, who attended an anti-choice protest! Boycott them to show them that this is not acceptable!"

3. The provisions of subdivision two of this section shall not be deemed to protect activity which:

a. creates a material conflict of interest related to the employer's trade secrets, proprietary information or other proprietary or business interest;

"Religious institutions have a First Amendment right to choose their teachers of religion, including based on the teachers' off-duty speech (as well as their race, sex, etc.)."

Why should this be limited to religious institutions? Let's say a private, secular school employs a teacher who blogs arguably racist content. School decides that such content is inimical to its educational mission. Why should the First Amendment not protect that school same as a religious school?

The government does not enjoy the protection of the First Amendment.

I said, a private, secular school.

The ministerial exception derives from the Free Exercise clause and thus does not apply to secular schools.

I know that. My point is, I do not see why the First Amendment should not protect that as well on free speech grounds. A school can have an educational mission and philosophy, and strive to promote that to its students. That certainly is protected by the First Amendment. So why should that not extend to what personnel the school employs?

The ministerial exception is based on the Freedom of Religion clause in the 1A. Your hypothetical would have to be based on a different clause. While I see your point about the moral equivalence, the legal path to get there would be ... less direct. It's not obvious to me that the Free Speech clause alone would be sufficient. It certainly wouldn't be as easy a call as the 'Religious Freedom → ministerial exception' was.

I acknowledge that it's a different legal basis. But I think the reasoning is the same.

People organize a school to promote a certain philosophy and educational system. THAT is certainly protected by the First Amendment. I don't think the state can interfere with a school's choice of philosophy. (It probably can insist on minimal educational standards.)

So why should that not extend to who it chooses to teach and promote that philosophy? At least teachers -- perhaps not the janitor. (Who I doubt would be within the ministerial exception for a religious school.)

Let me give an off-beat example. A school decides that it will promote veganism as a philosophy, viewing eating of animal products as cruel. It serves vegan food for lunch, and parents have to agree to maintain a vegan diet at home. A teacher is then found to blog about how she really enjoyed the steak that her husband cooked on the BBQ that weekend. That seems to me a good reason to fire her. I don't see how a statute like this one could prevent it consistent with the First Amendment.

While it is possible to view all schools as inculcating their students in preferred messages, justifying firing a disabled person seems a bit of a stretch when the message being taught is unrelated to the person being disabled. Now perhaps if the message is white supremacy, then firing a black teacher could pass muster (your vegan hypothetical probably passes muster as well). But, that would likely already be covered by expressive association under Dale (the Boy Scouts case).

For religious schools, firing a minister because they are disabled is assumed to be justified by the doctrine of the church. That is, the analogy to expressive association always applies to the employment of ministers.

That's not exactly right. The defendants in Hosanna–Tabor (the one involving a purportedly disabled teacher) did not take the position that "church doctrine" said that disabled people can/should be fired. They denied that they fired her for her disability, but took the position that the government had no business inquiring into why ministers were fired.

For many religious schools, blogging anti-racist content is a fireable offense.

Given the "ministerial exception", this should have been a very easy case. Houses of Worship can fire their religious staff for any reason.

A very dumb law. Attacking a largely non-existent problem I'd say.

Many of these job protections for recreational activity laws were originally passed to protect smokers.

I realize that courts would prefer to issue decisions on statutory grounds rather than constitutional ones, but given that there is a controlling Supreme Court decision directly on point here, and the statutory grounds are unsettled, it seems like an odd choice in this case.

Correction: I was misled by the post, or by my too-quick reading of it, at the very least. The court did rely on the ministerial exception.

…which was so obviously on point that I'm not sure why it wasn't sanctionable for the plaintiff to bring this case.

We shouldn't pretend that 'anti-zionism' is different from anti-semitism.