The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Chancellor James Kent on Hamilton's Federalist No. 77 and Modern Academic Commentary

A guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman.

I am happy to pass along this guest post from Professor Seth Barrett Tillman, which concerns how best to understand Alexander Hamilton's analysis in Federalist No. 77. This topic is once again very timely in light of the ongoing litigation over the President's removal power. And, once again, Tillman offers a correction to scholars who misread Hamilton. Make sure you read till the end.

***

As readers of this blog will know, there is a long-standing debate about the scope of the President's and Senate's appointment and removal powers. That debate has been shaped by the language of the Appointments Clause (referring to the Senate's "advice and consent" power), ratification era debates, including Hamilton's Federalist No. 77, debates in the First Congress, and, of course, subsequent executive branch practice, legislation, judicial decisions, and commentary.

In 2010, I attempted to make a modest contribution to this debate. Without opining either on the constitutional issue per se or on the meaning of the Appointments Clause, I argued that Hamilton's Federalist No 77 was not speaking to removal at all—at least, not removal as we think about it today.

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton stated: "The consent of th[e] [Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint." 20th century and 21st century commentators have uniformly understood Hamilton's "displace" language as speaking to "removal." (Albeit, there have been a few exceptions over the last one hundred years.) My modest contribution was to point out that "displace" has two potential meanings. "Displace" can mean "remove," but it can also mean "replace." This latter meaning is, in my view, more consistent with the overall language of the entire paragraph in which Hamilton's "displace as well as to appoint" statement appears.

Hamilton wrote:

It has been mentioned as one of the advantages to be expected from the co-operation of the senate, in the business of appointments, that it would contribute to the stability of the administration. The consent of that body would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint. A change of the chief magistrate therefore would not occasion so violent or so general a revolution in the officers of the government, as might be expected if he were the sole disposer of offices. Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained from attempting a change, in favour of a person more agreeable to him, by the apprehension that the discountenance of the senate might frustrate the attempt, and bring some degree of discredit upon himself. Those who can best estimate the value of a steady administration will be most disposed to prize a provision, which connects the official existence of public men with the approbation or disapprobation of that body, which from the greater permanency of its own composition, will in all probability be less subject to inconstancy, than any other member of the government. [bold and italics added]

Likewise, Hamilton, on other occasions, used "displace" in the "replace" sense. See, e.g., Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States [24 October 1800] ("But the truth most probably is, that the measure was a mere precaution to bring under frequent review the propriety of continuing a Minister at a particular Court, and to facilitate the removal of a disagreeable one, without the harshness of formally displacing him."); Alexander Hamilton to the Electors of the State of New York [7 April 1789] ("It has been said, that Judge Yates is only made use of on account of his popularity, as an instrument to displace Governor Clinton; in order that at a future election some one of the great families may be introduced.").

Similarly, Justice Story expressly adopted the "replace" view of Federalist No. 77. Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §§ 1532–1533 (Boston, Hilliard, Gray, & Co. 1833) ("§ 1532. … [R]emoval takes place in virtue of the new appointment, by mere operation of law. It results, and is not separable, from the [subsequent] appointment itself. § 1533. This was the doctrine maintained with great earnestness by the Federalist [No. 77] . . . ." (emphasis added)).

More recently, it appears, although one cannot be entirely sure, that Justice Kagan has adopted the "replace" interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Kagan wrote:

In Federalist No. 77, Hamilton presumed that under the new Constitution '[t]he consent of [the Senate] would be necessary to displace as well as to appoint' officers of the United States. He thought that scheme would promote 'steady administration': 'Where a man in any station had given satisfactory evidence of his fitness for it, a new president would be restrained' from substituting 'a person more agreeable to him.' [quoting Federalist No. 77] [bold added]

Seila Law LLC v. CFPB, 591 U.S. 197, 261, 270 (2020) (Kagan, J., concurring in the judgment with respect to severability and dissenting in part). "Substituting" is, in my opinion, akin to "replace."

However, in a 2025 article in California Law Review (at note 225), Professors Joshua C. Macey and Brian M. Richardson discuss both Federalist No. 77 and Joseph Story's interpretation of Federalist No. 77. Macey and Richardson wrote: "Joseph Story's Commentaries interpreted Federalist 77's reference to 'dismissal' to refer plainly to removal." There are three errors here. First, why is "dismissal" in quotation marks? It does not appear either in Federalist No. 77 or in Story's Commentaries, at least not in the sections under our consideration. Second, Story adopted the "displace" means "replace" view. And third, the issue is not "plain." We all make mistakes. In my view, this was a mistake on Macey and Richardson's part.

Macey and Richardson then write: "Notably, Chancellor [James] Kent, in a letter, attributed Story's interpretation to the original text of Federalist 77, an error which was repeated both in nineteenth-century histories of removal and by Chief Justice Taft's law clerk in connection with Taft's decision in Myers [v. United States]." Id. at note 225. Macey and Richardson cite two publications by Professor Robert Post in support of this view, but they do not cite any original, transcript, or reproduction of Kent's letter. This sentence of theirs is a Gordion knot. I have made some effort to cut this knot. Let me start by saying that, as best as I can tell, Kent's letter is from 1830, and Story wrote in 1833. So I suggest there was no way for Kent to attribute or misattribute anything by Story. Macey and Richardson are not entirely at fault. The error is in some substantial part Professor Robert Post's, and the concomitant error, by Macey and Richardson, is their (all too understandable) willingness to rely on Post and their failure to look up Kent's actual letter. Still, for reasons I explain below, Macey and Richardson have done modern scholars a valuable service—for which I thank them. (And, no, this is not sarcasm.)

To summarize: Macey and Richardson rely on Robert Post. Post is quoting Chief Justice Taft's researcher: William Hayden Smith. And William Hayden Smith is quoting Chancellor Kent. We are four levels deep—so, it is hardly surprising that one or more mistakes and misstatements creep into the literature.

Professor Post wrote:

[William Hayden] Smith replied on September 22 [1925] in a letter [to then-Chief Justice Taft] that cited scattered references and concluded that "I have deduced that executive included in its meaning the power of appointment and that sharing it with the legislative was extraordinary." Hayden Smith to WHT (September 22, 1925) (Taft [P]apers). Smith did not find much about the power of removal—the [Supreme Court] library was still looking for W.H. Rogers, The Executive Power of Removal—except that Chancellor Kent had in a letter written that although in 1789 "he [Kent] head leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word 'advice' must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in Federalist, no. 77, April 4th, 1788: 'No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate.' " [bracketed language added] [bold & italics added]

Robert C. Post, X.I The Taft Court / Making Law for a Divided Nation, 1921–1930, at 426–27 n.58 (CUP 2024); Robert Post, Tension in the Unitary Executive: How Taft Constructed the Epochal Opinion of Myers v. United States, 45 J. Sup. Ct. Hist. 167, 173 (2020) (same). The language above is simply too elliptical to clearly understand. "He said he had": Who is the "he" here, and whose voice is this: Kent or Smith on Kent? There is no reliable way to know what language here is Post's, and/or what is Smith's, and/or what is Kent's. Nor is there any good way to tell what here is a quotation and what has been rewritten (and by whom). The one thing which is clear is that Post leaves the reader with the impression that this passage is about removal.

What to do? All we can do is to examine the next level. That is: What did William Hayden Smith write in his letter to Taft?

Here is a link to the Letter from William Hayden Smith to Chief Justice Taft (Sept. 22, 1925). Smith wrote:

In [Senator Daniel] Webster[']s Private Correspondence, vol.1, pp.486-7, there is a letter from Chancellor Kent upon the subject. After remarking that at the time of the debate in 1789, he had leant toward Madison, but now (1830) because of the word "advice" must have meant more than consent to nomination, he said he had a strong suspicion that Hamilton was right in his remark in the Federalist, no.77, April 4th, 1788: "No one could fail to perceive the entire safety of the power of removal if it must thus be exercised in conjunction with the senate." [italics added] [bold and italics added]

There are two problems with the passage above, one internal to the passage, and one external to it, as quoted by Post and others.

First: the minor error. The sentence in bold and italics is from Story's 1833 Commentaries on the Constitution—it is not from Federalist No. 77. And Kent's letter is from 1830—so that sentence is not likely from Kent either (unless Story lifted it from Kent's writings [which I have no good reason to suspect], or Kent was a time traveller [ditto]). The mistake here is Smith's, and Post's quoting Smith without explanation, and those quoting Post without examining the underlying chronological problem.

Second: the major error. The Smith passage above is the penultimate full paragraph of the letter. What has gone unreported is how Smith ends his letter. Smith, on the top of the next (that is, the last) page of his letter, wrote:

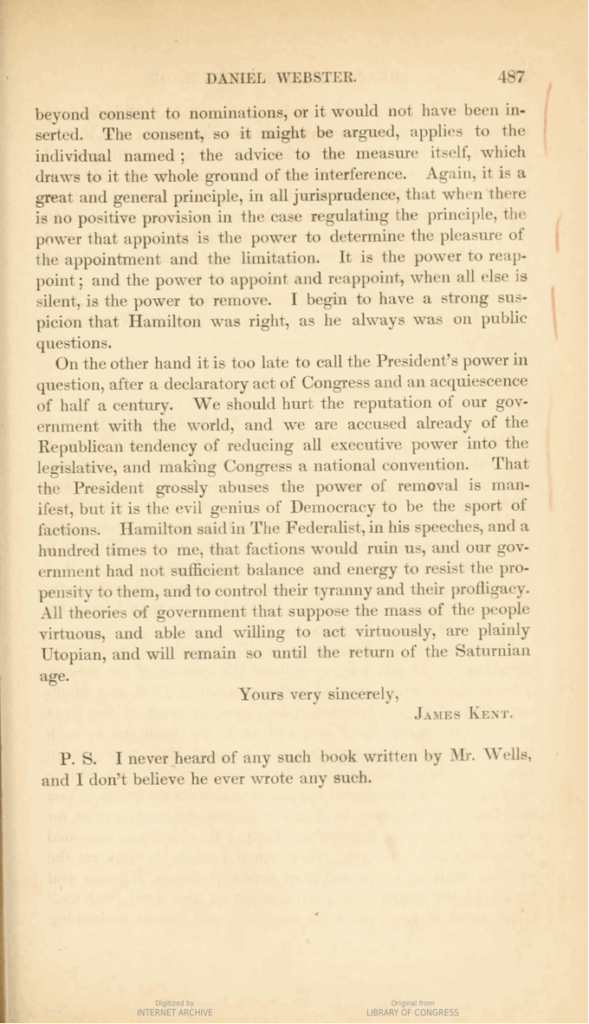

Kent went on to say that there was a general principle in jurisprudence that the power that appoints is the power to determine the pleasure and limitation of the appointment. The power to appoint, he said must also include the power to re-appoint, and the power to appoint and reappoint when all else is silent is the power to remove. However, Kent concluded that he would not call the president[]s power in[to] question as "it would hurt our reputation abroad, as we are already becoming accused of the tendency of reducing all executive power to legislative." [italics added] [hyphen added]

This last full paragraph, which has gone unreported in the modern literature, inverts the common understanding of the prior paragraph—a paragraph which has been reported by Post and others. As I understand Kent, he is saying that absent tenure in office, the President and Senate collectively can appoint to vacant positions, and they can also appoint to occupied positions. An appointment of the latter type works a constructive removal. That's the "removal" power under discussion in Federalist No. 77. In terms of a free-standing presidential removal power, Kent acknowledges that one has sprung from practice and by statute, and he chooses not to question the president's use of such a removal power for political reasons. In other words, Kent, like Story, read Federalist No. 77's "displace" language to refer to "replace," and not to "removal" per se or removal simpliciter.

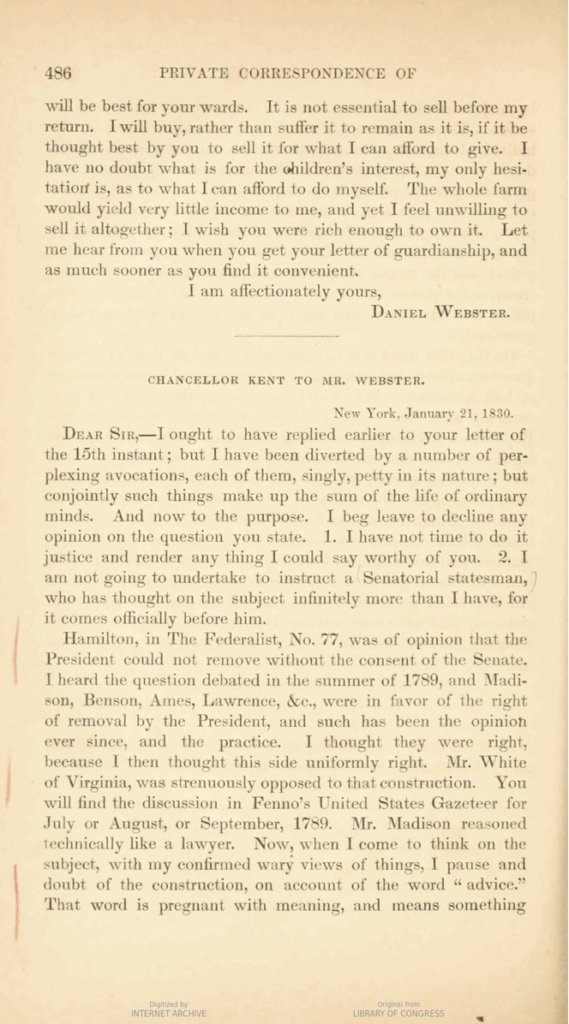

That takes us to Kent's January 21, 1830 letter. You can read it here—at page 486 (just as reported by William Hayden Smith)—courtesy of the HathiTrust website.

Kent stated:

Again, two points here. The troubling statement from Story does not appear in the Kent letter. How could it? And the only removal power under discussion in Federalist No. 77 is the power to appoint and re-appoint, with the latter working a constructive removal. The power of the President to remove (as in a pure removal, absent any successive or subsequent appointment) arose in connection with a purported congressional declaratory act and acquiescence by congress or the public or both. That sort of removal, according to Kent, was not under discussion in Federalist No. 77. At least, that is my reading of these documents.

I thank Professors Macey and Richardson for teeing this issue up. In doing so, they have helped start a process leading to the clarification of a messy historical literature. As for Professor Post—we all make mistakes. Certainly, I am not faulting him. And I am not faulting, in any way, Professor Bailey for adhering to the traditional Hamilton meant removal in Federalist No 77 view during our 2010 debate on the issue. There is certainly evidence on both sides of the issue—that is: What did Hamilton mean by "displace"?

Still, it is troubling—more than slightly troubling—that unlike Professor Bailey, any number of academics and historians have played let's pretend and announced, as if God, that all evidence points conclusively in one direction. Historical and interpretive questions are rarely so simple. Frequently, there is a majority and a minority view, if not more than two such views, and a stronger/better view and a weaker/lesser view. And after hundreds of years, it is difficult for moderns to identify which was or is which. But pretending that there are not competing ideas and ideals undercuts our understanding and our efforts at fair-play, and when all this is done by academics, it teaches students little more than adherence to authority, political correctness, and wokism. If academics cannot be reasonably fair in voicing disagreement, at least they should strive to be cautious—given that their favored theories may be falsified by one heretofore unknown document. Editors at journals and publishing houses who publish such one-sided materials fail to understand one of their key missions—which is to rein in the excess that comes from debate participants, who may have a fair point to make, but who have lost perspective. I know that my publications have frequently benefited from editors who advised me to moderate my language. If editors refuse to do this, than Professor Brian Frye will (and should) have his dream—a world without journals replaced by papers only "published" on the Social Science Research Network. That "is the long and short of it." Jonathan Gienapp, Removal and the Changing Debate over Executive Power at the Founding, 63 Am. J. Legal Hist. 229, 238 n.55 (2023) (peer review); see also Ray Raphael, Constitutional Myths: What We Get Wrong and How to Get It Right 278 n.38 (2013).

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"...And third, the issue is not "plain." We all make mistakes. In my view, this was a mistake on Macey and Richardson's part. ..."

Threadjack, to ask a grammar question. When does one use, "...Macey & Richardson's part...", and when does one use, "...Macey's and Richardson's part..."??? I've never thought about this before.

"I borrowed Josh, Eugene, and Susan's notes for the rehearsal." That makes it sound like I borrowed Josh and Eugene (as scene partners, perhaps?), and also borrowed Susan's notes. But if I write, "I borrowed Josh's, Eugene's, and Susan's notes...", then that sort of looks like 3 separate sets of notes, rather than the one set of notes that belongs to the 3 of them.

Is it a context-dependent thing? Is there a hard-and-fast rule I've never learned? Or is this just an example of English being a funny language; so if one of our students had such a sentence, we'd tell them, "Rewrite it, so it's clear what you meant."?

Depends....

To show that two or more nouns collectively possess an item, change only the final noun to the possessive case.

Example of the possessive form for multiple nouns that possess the same item: Anne, Hannah, and Tim’s new cat is really playful.

To show that two or more nouns individually possess the same item, change all the nouns to the possessive case.

Example of the possessive form for two nouns that separately possess items: Both Chelsea’s and Emily’s lunchboxes are orange.

(APA Style)

Whatever that mish-mash in the OP is intended to mean, I can help with a simpler idea. Whether this will be in concert with Federalist 77 or not I leave to others to judge.

The simpler point I advocate is that questions of removal from office for oath-sworn officials who do not hold their positions by election ought to get answered by review of fidelity to their oaths. And the party doing the review ought to be the party which required the oaths in the first place. In all cases of Constitutionally required oaths, that party would be the jointly sovereign People themselves. No other government parties are properly empowered to judge the People's own satisfaction with an oath-bound office-holder's performance.

Thus, a customary view that an appointing authority—the president of the United States, for instance—is by virtue of making an appointment empowered likewise to dismiss the officeholder at pleasure, is mistaken. It is a view neither analogous, nor complementary, with an appointment process involving an oath to the People, not to the party making the appointment. The President in every case of an oath-sworn appointment has made that choice in concert with the People themselves. An officeholder sworn to allegiance to the People is not thereby made a vassal of the appointing government authority.

Experience has shown it has been a mistake to impute such unconstrained powers to governments, while it has never been the intent in American constitutionalism to leave governments unconstrained by the jointly sovereign People. While appointed officials remain faithful to their oaths—as decided by the People to whom they swore the oaths—those oath-sworn officials remain an indispensable part of the mechanism of government constraint. Examples of that concept surface when elected officials exceed their own Constitutional bounds, which happens all too frequently.

Sometimes, those examples take the form of foot-dragging along a road to Constitutional non-compliance. That can make government inefficient, in a good way.

Often, those examples take the form of resignations by officials who recognize that political superiors have demanded oath breaking conduct. Time and again in American experience, resignations of that sort have delivered timely alarms, which the People heeded, and corrupt politicians ignored at their peril.

If anything, a mechanism to strengthen that salutary process is what is needed now. To further empower a norm to let politicians ignore oath-keeping by their appointed subordinates, and to replace them at pleasure, or upon whim, or simply to frighten others into unwilling Constitutional non-compliance, is unwise. If this political moment shows us anything, it shows that.

Speaking of mish-mash, many many words here that don't really say anything. I have no idea what you think you mean by oath-sworn officials, since every person in federal service is required to take an oath to support the Constitution, not the "People". Nobody agrees on what constraints look like. At any rate, the question is not about constraints or even compliance, but executing the laws and whether subordinates are always doing so according to the president's desire, or independently as they understand the law.

Nobody agrees on what constraints look like.

Hence, no constraints?

An oath to support the Constitution is as useless as no oath at all, unless there is some party to say whether it has been kept or dishonored. Is no oath at all what you prefer?

If not, the only conceivable party to say whether an oath has been kept or dishonored is the author of the Constitution, which is now, as always, the jointly sovereign People. They are the only party with legitimate power to constrain government. They are the party to which the oath is sworn. It is not sworn to the Congress, to the Executive, or to the Judiciary. And the Constitution is not a party at all. It is a document, expressing a decree. The People are the party to which the oath is sworn.

You tautology still doesn't say anything. You just want your preferences/understanding of constraints to govern, but you can't say how that might be. Beyond having others in various positions of authority agree with you. And I suppose those subordinate to a president you disagree with be allowed to defy him. I am unaware of any rational concept where a subordinate can constraint a superior.

Of course, the Constitution has its structural separation of powers which actually a mechanism to implement this. But that has nothing to do with the "People" or oaths. Or the power of removal, except as that is the very thing being contested: whether/how Congress can constrain the president's power of removal by law. Nothing to do with oaths or jointly sovereign People. Or what Hamilton wrote about.

.

Hamilton changed his mind on the particulars of the question.

It was a question that the First Congress split over multiple ways.

Parsing what he said in an op-ed has some academic interest. What it tells us about what we should decide the matter is limited.

It seems to me that Tillman is missing the wood for the trees. The puzzle of Mackey and Richardson’s paper is solved by some text that Tillman notes but fails to comment upon.

Their paper is from 2025.

John Adams to Timothy Pickering (May 12, 1800)

The position of Tillman (and Justice Story, Chief Justice Taft, [seemingly] Justice Kagan, and countless others for more than 200 years) - that by "displace", Hamilton meant "replace" rather than "remove" - is the only sound and logical interpretation. Frankly, the opposite position, which I am seeing today expressed for the first time - is absurd.

If Hamilton were indeed meaning "remove", then he is not saying that the Congress may require advise and consent for removal, but that the Constitution mandates it. Even in the debates in the First Congress favoring removal restrictions, I am unaware of a single individual suggesting this was the case.

The case of Timothy Pickering is illustrative. Pickering served as Postmaster General, then Secretary of War, then Secretary of State under President Washington. After John Adams was elected in 1796, Pickering stayed on as Secretary of State. Adams and Pickering fell out because Pickering was actively undermining Adams' peace efforts with France. Pickering (like Hamilton) was unabashedly pro-British and, behind Adams' back, was communicating with others (including Hamilton) about ways to derail the peace process, including a scheme to get Hamilton appointed a Major General in the Army. Adams asked Pickering to resign, but he refused, so Adams fired him.

Had Hamilton really believed Adams needed the approval of the Senate to fire Pickering, it seems he really would have taken the opportunity to say so at the time, though, as far as I know, he did not.

“It has been said, that Judge Yates is only made use of on account of his popularity, as an instrument to displace Governor Clinton; in order that at a future election some one of the great families may be introduced.”

How is this a use of “displace” to mean “replace” rather than “remove”? It seems more like a reference to immediate removal so that the position may later be filled by someone else.

I think it could be read either way. It seems that Judge Yates was thought to be popular enough to defeat Governor Clinton in an election, by folk who really wanted Clinton out and “someone of the great families” in. ie those willing to back Yates as a placeholder mostly wanted Clinton removed- hence you can read displace as “remove.”

But because this was an election Clinton could only be removed by somebody else beating him in the election, ie the “displacement” was necessarily a replacement. The removal of Clinton required his replacement by Yates - simple removal was not available. Because it’s removal by election it’s a different animal from removal of a federal office holder, generating a vacancy, which is then filled by appointment as a separate act.

So you can just as well read it as “replace” instead. Since it could be taken either way, I’m not sure it’s a great example.

The most common spelling is "Gordian" knot

Now that we have answered the question as to whether the Constitution limits the president's removal powers (no), we have a second question: can Congress limit the president's removal powers with legislation? The logical answer is not an all or nothing proposition: Congress can't limit the president's powers to fire cabinet officials, but can limit the president's power to fire lesser appointees, such as federal reserve board members. But in today's constitutional law world, we seem to get a lot of all or nothing arguments.

The second amendment comes to mind as another example of this phenomenon

If a president has unrestricted removal power, then he may simply remove an officer and appoint a new one with the advice and consent of the Senate, consistent with Hamilton's direction that "the consent of that body would be necessary ... to appoint." But that is exactly how a "displacement" would occur, at least in the context of an unrestrained removal power. So why would Hamilton distinguish between "displace" and "appoint"?

There are only two interpretations that don't deprive "displace" of any meaning. First, because a replacement can only occur upon the removal of the preceding official, the Senate must consent to the removal of an officer so that the president can appoint a replacement. Second, the president can appoint a replacement, but the removal will take only upon the Senate's approval of that appointment.

This is explained in Tillman’s piece in the paragraph beginning “Similarly, Justice Story…”

Displacement is described as the appointment of a new officer, whose appointment “by mere operation of law” removes the sitting officer. Thus you can have appointment on its own without removal, eg if the office holder has died or resigned, or if Congress creates a new office. Or you can have removal on its own where the sitting officer is removed but the President doesn’t get round to appointing a new guy. Or you can have displacement aka replacement where the President appoints a new guy and the old guy loses his office without any action required because the new guy is sitting at his desk.

The first and the third which include appointment require the Senate’s consent - if it is a principal officer. The second does not.