The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

First Amendment Claim Over Firing of Firefighter for Supposedly Racially Offensive Anti-Abortion Post Can Go Forward

From today's decision in Melton v. City of Forrest City, written by Judge David Stras, joined by Judges Lavenski Smith and Ralph Erickson:

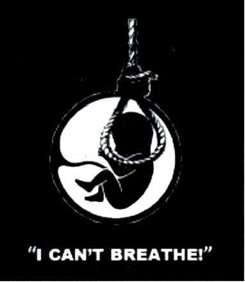

Steven Melton is a pro-life, evangelical Christian. In June 2020, he reposted a black-and-white image on Facebook that depicted a silhouette of a baby in the womb with a rope around its neck. His intent was to convey that he was "anti-abortion."

Others did not view the image the same way. Two weeks after he posted it, a retired fire-department supervisor complained to Melton that he thought it looked like a noose around the neck of a black child. It upset him because the caption of the image, "I can't breathe!," was associated with the protests surrounding George Floyd's death. Melton agreed to delete it immediately.

Deleting it was not enough for Mayor Cedric Williams, who called him into his office the next day. Although Melton was "apologetic," the mayor placed him on administrative leave pending an investigation. After a single day reviewing Melton's Facebook page and discussing the post with the current fire chief, two retired firefighters, several attorneys, and a human-resources officer, the mayor decided to fire Melton over the image's "egregious nature."

He was concerned about the "huge firestorm" it had created. Among other things, the fire chief's phone had been "blowing up," "several" police officers had become "very upset," and the "phone lines" were jammed with calls from angry city-council members and citizens. Some said that Melton "should not be a part of the … fire department responding to calls." A few even said that they did not want "him coming to their house … for a medical call or fire emergency." According to the mayor, these complaints "threaten[ed] the City's ability to administer public services."

Melton was fired; he sued, claiming the firing violated the First Amendment, and the court allowed the claim to go forward:

Public employees "must," according to the Supreme Court, "accept certain limitations on [their] freedom," because the government has valid "interests as an employer in regulating the[ir] speech," Recognizing, however, that they "do not surrender all their First Amendment rights by reason of their employment," the Court has staked out a middle ground. (emphasis added). Known as Pickering balancing, it requires weighing the government's interest "in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees" against the employee's interest "in commenting upon matters of public concern." Pickering v. Bd. of Educ. (1968). Courts weigh these interests on a post hoc basis, long after the speech and the alleged retaliation have come and gone. It is no easy task.

Getting there even involves addressing a couple of threshold issues, one for each side. For Melton, he can bring a claim for retaliation only if he was speaking "as a citizen on a matter of public concern." Then the focus shifts to the government employer to establish that the speech "created workplace disharmony, impeded [Melton's] performance, … impaired working relationships," or otherwise "had an adverse impact on the efficiency of the [fire department's] operations." Only if both are true will we do a full Pickering balancing and weigh these interests against each other.

The record is clear on the first issue. Melton posted the image to his personal page on his own time, and there is no dispute that race and abortion are matters of "political, social, or other concern to the community." From there, the "possibility of a First Amendment claim ar[ose]" out of the "individual and public interest[]" in Melton's speech.

The record is more of a tossup on whether there was a negative impact on Forrest City's delivery of "public services." Sometimes a government employer will experience an actual disruption. Other times, it will have a "reasonabl[e] belie[f]" in "the potential for disruption." Either is usually enough when the government entity is a public-safety organization. But when neither is present, there are "no government interests in efficiency to weigh" and Pickering balancing "is unnecessary."

At best, the evidence of disruption is thin. As the district court pointed out, everyone agrees "that there was no disruption of training at the fire department, or of any fire service calls, because of the post or the controversy surrounding it." Instead, Mayor Williams argues that the "firestorm" itself is what "disrupted the work environment." "[S]everal" police officers and city-council members were upset and "phone lines [were] jammed" with calls from concerned citizens. A few opposed Melton's continued employment as a firefighter and did not want him "coming to their house … for a medical call or fire emergency." These calls seemed to be the main motivation for firing Melton.

The problem is that there was no showing that Melton's post had an impact on the fire department itself. No current firefighter complained or confronted him about it. Nor did any co-worker or supervisor refuse to work with him. Granting summary judgment based on such "vague and conclusory" concerns, without more, runs the risk of constitutionalizing a heckler's veto. Enough outsider complaints could prevent government employees from speaking on any controversial subject, even on their own personal time. And all without a showing of how it actually affected the government's ability to deliver "public services"—here, fighting fires and protecting public safety.

Much of what remained was predictive. Mayor Williams claimed, for example, that "conveying racist messages against Black people [would] affect trust between firefighters." To provide a "reasonable prediction[]" sufficient to take the case away from a jury, a decisionmaker must do more than make a vague statement in response to a conditionally worded question about what could happen. When the record and the prediction do not match, it will usually be up to the jury to resolve the discrepancy and determine whether the prediction was reasonable enough to be entitled to "substantial weight."

What the district court should not have done was automatically give the mayor's belief "considerable judicial deference." As one of our cases puts it, "we have never granted any deference to a government supervisor's bald assertions of harm based on conclusory hearsay and rank speculation." Keep in mind that, in addition to the lack of evidence supporting the mayor's prediction, his brief investigation could lead a reasonable jury to conclude that what he said masked the true reason for Melton's firing, which was a disagreement with the viewpoint expressed in the image. The jury's role will be to resolve these factual disputes "through special interrogatories or special verdict forms." The district court can then decide, based on "the jury's factual findings," whether Melton's speech was protected.

And the court concluded that the law here was "clearly established," so Melton's claim couldn't be dismissed on qualified immunity grounds:

Insufficient evidence of a disruption would be "fatal to the claim of qualified immunity" because there would be no governmental interest to weigh. If the jury finds sufficient evidence of disruption to get to Pickering balancing, on the other hand, then "the asserted First Amendment right [is] rarely considered clearly established."

Frank H. Chang and John Michael Connolly (Consovoy & McCarthy) and Chris P. Corbitt and David Ray Hogue (Hogue & Corbitt) represent Melton.

Show Comments (18)