The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

"I Eat Ass" Bumper Sticker Might Be Obscene and Thus Constitutionally Unprotected

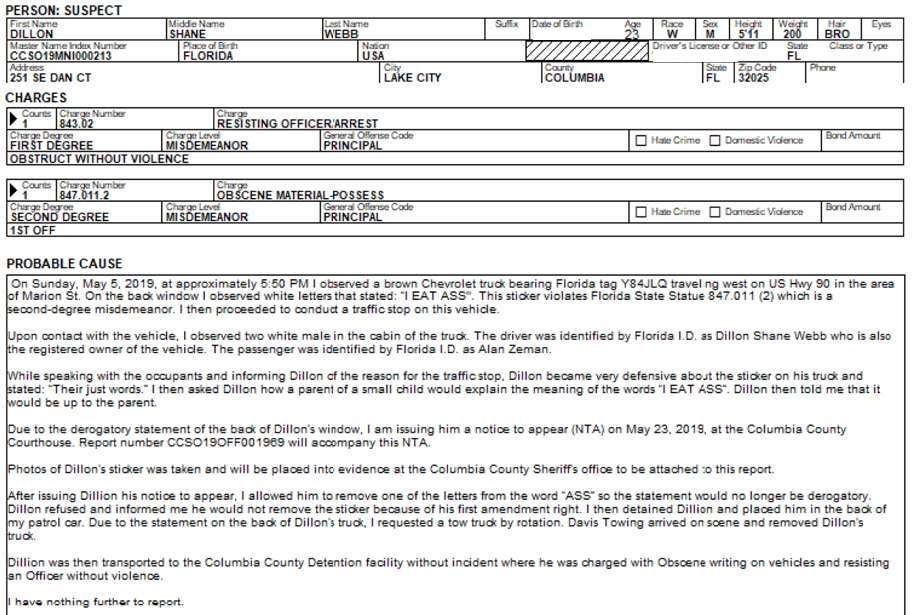

So holds a district court, concluding that the law is unclear enough that a police officer was entitled to qualified immunity based on his arresting a man for the sticker.

I reasoned, in part, that the sticker wasn't obscene under the Florida statute, which tracks the Supreme-Court-approved definition of obscenity:

(10) "Obscene" means the status of material which:

(a) The average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest;

(b) Depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct as specifically defined herein; and

(c) Taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

This couldn't constitutionally apply to Dillon's speech, because to be obscene, expression "must be, in some significant way, erotic," and must tend to arouse "lustful thoughts" or "sexual responses" and not just refer to sexual acts. Hard-core pornography might be obscene, especially if displayed in public; but this sort of vulgar verbal reference to a sexual act is far from hard-core pornography.

Well, "The State Attorney's Office for the Third Judicial Circuit ultimately determined Webb had a valid defense to the charges under the First Amendment and, as such, dropped the charges against him." But Judge Marcia Morales Howard determined that the matter was uncertain enough that the sheriff's deputies who arrested Dillon were entitled to qualified immunity:

Deputy English and Corporal Kirby subjectively interpreted the Sticker as depicting a sexual act and believed that the Sticker violated Florida's obscenity statute. While Webb denies the Sticker was in fact obscene, in interviews he repeatedly acknowledged the sexual nature of his Sticker, albeit couched as an attempt at humor, showing that the notion that an erotic message was more than hypothetical—it could reasonably be viewed as the predominant message being communicated. Indeed, others in the videos similarly acknowledged, both directly and indirectly, that the Sticker described a sexual act. Given this evidence, including Webb's own statements, it is beyond dispute that reasonable officers possessing the same knowledge as Deputy English and Corporal Kirby could have thought the Sticker depicted a sexual act, and as such [was arguably obscene].

{The Court notes there is no inherent conflict between Webb's intention to elicit laughter with his Sticker and it being obscene. The two are not mutually exclusive and Webb's suggestion that his intent to bring about laughter forecloses any argument that the Sticker was obscene is unsupported by case law.}

If the Sticker depicted a sexual act, it would be protected speech under the First Amendment only if it had serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. {While Webb presents evidence that the phrase is widely used, such evidence does not mean the phrase has serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value, see Luke Records (rejecting the notion that the value of a work depends on the acceptance it receives; finding instead expert testimony that a record's music contained oral traditions and musical conventions that had cultural and political significance to be evidence in support of the third Miller element).} However, in such an instance, Deputy English and Corporal Kirby had to make a value judgment on whether the Sticker had such serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value in deciding whether to arrest Webb. Notably, the Eleventh Circuit has recognized that value judgments are inherently difficult to review, which is why law enforcement officers are immune from suit if their value judgments are supported by arguable probable cause…. Here, Deputy English and Corporal Kirby's determination that the Sticker lacked serious value under Florida law was not inherently unreasonable under the circumstances. As such, the Court finds reasonable officers in the same circumstances and with the same knowledge as Deputy English and Corporal Kirby could believe Webb's Sticker was obscene, making it an arrestable offense under Florida law….

[C]iting Baker v. Glover (M.D. Ala. 1991), Webb argues that the constitutionally protected nature of his speech was clearly established because the Sticker merely contained non-obscene, though foul, language. However, this argument fails for two reasons. First, decisions at the district court level, like the one in Baker, are insufficient to clearly establish the law for purposes of a qualified immunity analysis. Instead, "only decisions of the United States Supreme Court, [the Eleventh Circuit], or the highest court in a state can 'clearly establish' the law." Second, the Baker decision is not particularly persuasive because it is distinguishable in important respects. In Baker, the plaintiff had a bumper sticker that read, "How's My Driving? Call 1–800–EAT S***!" [The bumper sticker actually spelled out "SHIT." -EV] … Though the defendants in the case went to great lengths to correlate the consumption of feces with a sexual act such that it would constitute obscenity, the trial court rejected the argument noting that it was "unpersuaded that a facetious message employing a single profane word could be viewed as carrying such an abnormal appeal." In other words, the Baker court found Baker's "EAT S***" bumper sticker was not erotic in nature, and therefore could not be obscene expression falling outside the protection of the First Amendment. {As recognized by the Supreme Court, obscene expression that is not protected by the First Amendment "must be, in some significant way, erotic." Cohen v. California.} The language of Baker's bumper sticker, however, is materially different than the one displayed by Webb such that the Baker decision fails to qualify as "caselaw with indistinguishable facts." …

Critically, the Court does not have to determine whether Webb's Sticker was in fact obscene for qualified immunity to apply. And, the Court makes no such finding here. Rather, Webb's burden was to show that at the time of his arrest it was clearly established that his Sticker was constitutionally protected speech, i.e. not obscene. The lack of any case even closely on point dooms Webb's effort to make that showing. On this record, the undisputed facts establish the Sticker could be interpreted by the parties and others as describing a sexual act. If interpreted to refer to a sexual act, the Sticker is arguably obscene and unprotected by the First Amendment. The lack of comparable case law and the fact that the obscene nature of the Sticker is debatable is precisely why Webb's argument that he had a clearly established right fails….

I don't think this is right; obscenity is limited to "hard-core pornography," and it's hard for me to see how a short vulgar description of sex such as "I eat ass" would qualify. Still, Judge Howard wears the robe and I don't.

Show Comments (40)