The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

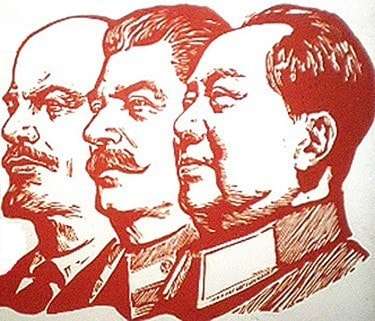

Lessons from a century of communism

Today is the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik seizure of power, which led to the establishment of a communist regime in Russia and eventually in many other nations around the world. It is an appropriate time to remember the vast tide of oppression, tyranny, and mass murder that communist regimes unleashed upon the world. While historians and others have documented numerous communist atrocities, much of the public remains unaware of their enormous scale. It is also a good time to consider what lessons we can learn from this horrendous history.

I. A Record of Mass Murder and Oppression.

Collectively, communist states killed as many as 100 million people, more than all other repressive regimes combined during the same time period. By far the biggest toll arose from communist efforts to collectivize agriculture and eliminate independent property-owning peasants. In China alone, Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward led to a man-made famine in which as many as 45 million people perished - the single biggest episode of mass murder in all of world history. In the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin's collectivization - which served as a model for similar efforts in China and elsewhere - took some 6 to 10 million lives. Mass famines occurred in many other communist regimes, ranging from North Korea to Ethiopia. In each of these cases, communist rulers were well aware that their policies were causing mass death, and in each they persisted nonetheless, often because they considered the extermination of "Kulak" peasants a feature rather than a bug.

While collectivization was the single biggest killer, communist regimes also engaged in other forms of mass murder on an epic scale. Millions died in slave labor camps, such as the USSR's Gulag system and its equivalents elsewhere. Many others were killed in more conventional mass executions, such as those of Stalin's Great Purge, and the "Killing Fields" of Cambodia.

The injustices of communism were not limited to mass murder alone. Even those fortunate enough to survive still were subjected to severe repression, including violations of freedom, of speech, freedom of religion, loss of property rights, and the criminalization of ordinary economic activity. No previous tyranny sought such complete control over nearly every aspect of people's lives.

Although the communists promised a utopian society in which the working class would enjoy unprecedented prosperity, in reality they engendered massive poverty. Wherever communist and noncommunist states existed in close proximity, it was the communists who used walls and the threat of death to keep their people from fleeing to societies with greater opportunity.

II. Why Communism Failed.

How did an ideology of liberation lead to so much oppression, tyranny and death? Were its failures intrinsic to the communist project, or did they arise from avoidable flaws of particular rulers or nations? Like any great historical development, the failures of communism cannot be reduced to any one single cause. But, by and large, they were indeed inherent.

Two major factors were the most important causes of the atrocities inflicted by communist regimes: perverse incentives and inadequate knowledge. The establishment of the centrally planned economy and society required by socialist ideology necessitated an enormous concentration of power. While communists looked forward to a utopian society in which the state could eventually "wither away," they believed they first had to establish a state-run economy in order to manage production in the interests of the people. In that respect, they had much in common with other socialists.

To make socialism work, government planners needed to have the authority to direct the production and distribution of virtually all the goods produced by the society. In addition, extensive coercion was necessary to force people to give up their private property, and do the work that the state required. Famine and mass murder was probably the only way the rulers of the USSR, China, and other communist states could compel peasants to give up their land and livestock and accept a new form of serfdom on collective farms - which most were then forbidden to leave without official permission, for fear that they might otherwise seek an easier life elsewhere.

The vast power necessary to establish and maintain the communist system naturally attracted unscrupulous people, including many self-seekers who prioritized their own interests over those of the cause. But it is striking that the biggest communist atrocities were perpetrated not by corrupt party bosses, but by true believers like Lenin, Stalin, and Mao. Precisely because they were true believers, they were willing to do whatever it might take to make their utopian dreams a reality.

Even as the socialist system created opportunities for vast atrocities by the rulers, it also destroyed production incentives for ordinary people. In the absence of markets (at least legal ones), there was little incentive for workers to either be productive or to focus on making goods that might actually be useful to consumers. Many people tried to do as little work as possible at their official jobs, where possible reserving their real efforts for black market activity. As the old Soviet saying goes, workers had the attitude that "we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay."

Even when socialist planners genuinely sought to produce prosperity and meet consumer demands, they often lacked the information to do so. As Nobel Prize-winning economist F.A. Hayek described in a famous article, a market economy conveys vital information to producers and consumers alike through the price system. Market prices enable producers to know the relative value of different goods and services, and determine how much consumers value their products. Under socialist central planning, by contrast, there is no substitute for this vital knowledge. As a result, socialist planners often had no way to know what to produce, by what methods, or in way quantities. This is one of the reasons why communists states routinely suffered from shortages of basic goods, while simultaneously producing large quantities of shoddy products for which there was little demand.

III. Why the Failure Cannot be Explained Away.

To this day, defenders of socialist central planning argue that communism failed for avoidable contingent reasons, rather than ones intrinsic to the nature of the system. Perhaps the most popular claim of this sort is that a planned economy can work well so long as it is democratic. The Soviet Union and other communist states were all dictatorships. But if they had been democratic, perhaps the leaders would have had stronger incentives to make the system work for the benefit of the people. If they failed to do so, the voters could "throw the bastards out" at the next election.

Unfortunately, it is unlikely that a communist state could remain democratic for long, even it started out that way. Democracy requires effective opposition parties. And in order to function, such parties need to be able to put out their message and mobilize voters, which in turn requires extensive resources. In an economic system in which all or nearly all valuable resources are controlled by the state, the incumbent government can easily strangle opposition by denying them access to those resources. Under socialism, the opposition cannot function if they are not allowed to spread their message on state-owned media, or use state-owned property for their rallies and meetings. It is no accident that virtually every communist regime suppressed opposition parties soon after coming to power.

Even if a communist state could somehow remain democratic over the long run, it is hard to see how it could solve the twin problems of knowledge and incentives. Whether democratic or not, a socialist economy would still require enormous concentration of power, and extensive coercion. And democratic socialist planners would run into much the same information problems as their authoritarian counterparts. In addition, in a society where the government controls all or most of the economy, it would be virtually impossible for voters to acquire enough knowledge to monitor the state's many activities. This would greatly exacerbate the already severe problem of voter ignorance that plagues modern democracy.

Another possible explanation for the failures of communism is that the problem was bad leadership. If only communist regimes were not led by monsters like Stalin or Mao, they might have done better. There is no doubt communist governments had more than their share of cruel and even sociopathic leaders. But it is unlikely that this was the decisive factor in their failure. Very similar results arose in communist regimes with leaders who had a wide range of personalities. In the Soviet Union, it is important to remember that the main institutions of repression (including the Gulags and the secret police) were established not by Stalin, but by Vladimir Lenin, a far more "normal" person. After Lenin's death, Stalin's main rival for power - Leon Trotsky - advocated policies that were in some respects even more oppressive than Stalin's own. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that either the personality of the leader was not the main factor, or - alternatively - communist regimes tended to put horrible people to positions of power. Or perhaps some of both.

It is equally difficult to credit claims that communism failed only because of defects in the culture of the countries that adopted it. It is indeed true that Russia, the first communist nation, had a long history of corruption, authoritarianism, and oppression. But it is also true that the communists engaged in oppression and mass murder on a far greater scale than previous Russian governments. And communism also failed in many other nations with very different cultures. In the cases of Korea, China, and Germany, people with very similar initial cultural backgrounds endured terrible privation under communism, but were much more successful under market economies.

Overall, the atrocities and failures of communism were the natural outcomes of an effort to establish a socialist economy in which all or nearly all production is controlled by the state. If not always completely unavoidable, the resulting oppression was at least highly likely.

Just as the atrocities of Nazism are abject lessons on the dangers of nationalism, racism, and anti-semitism, so the history of communist crimes teaches the dangers of socialism. The history of communism does not prove that any and all forms of government intervention in the economy must be avoided. But it does highlight the dangers of allowing the state to seize control of all or most of the economy, and of eliminating private property. Moreover, the knowledge and incentive problems that arise under socialism also bedevil efforts at large-scale economic planning that fall short of complete government control of production.

Sadly, these lessons remain relevant today, in an era where socialism has again begun to attract adherents in various parts of the world. In Venezuela, the government is seeking to establish a new socialist dictatorship that pursues many of the same policies as the old, including even the use of food shortages to break opposition. Even in some long-established democracies, recent economic and social troubles have increased the popularity of avowed old-style socialists such as Bernie Sanders in the United States and Jeremy Corbyn in Britain. Both Sanders and Corbyn are longtime admirers of brutal communist regimes. Even if they wanted to do so, it is unlikely that Sanders or Corbyn will be able to establish full-blown socialism in their respective countries. But they can potentially do considerable harm nonetheless.

On the other side of the political spectrum, there are disturbing similarities between communism and various newly popular extreme right-wing nationalist movements. Both combine authoritarian tendencies with disdain for liberal values and a desire to extend government control over large parts of the economy.

Today's dangerous tendencies on both right and left are not yet as menacing as those of a century ago, and need not cause anywhere near as much harm. The better we learn the painful lessons of the history of communism, the more likely that we can avoid any repetition of its horrors.

Show Comments (0)