The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

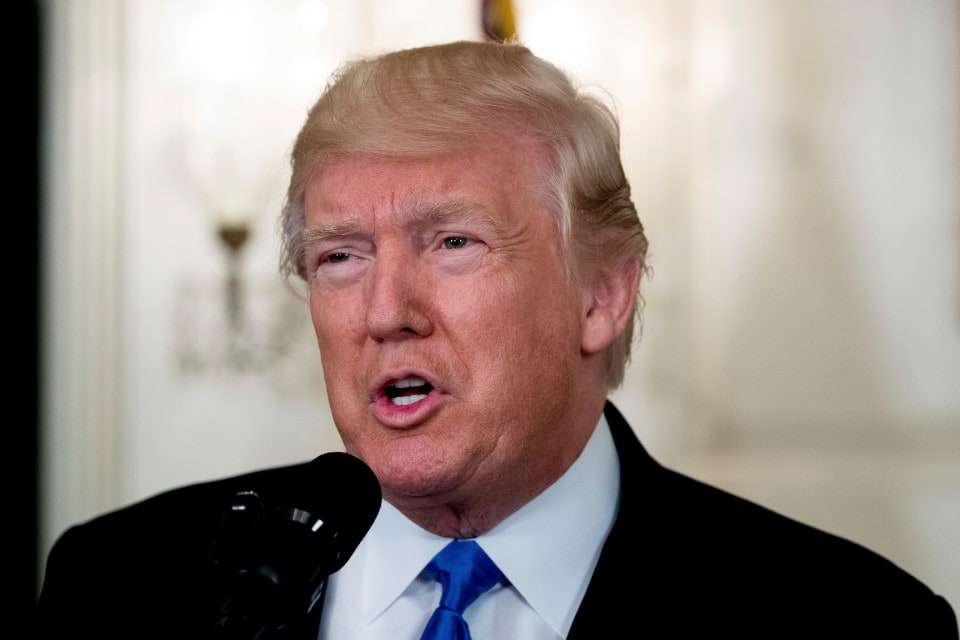

New Foreign Emoluments Clause lawsuits against Trump are up against history and standing

Recent days have seen several developments in Foreign Emoluments Clause litigation against President Trump. On Friday, the Justice Department filed its brief in the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) case (using a variety of arguments developed by academics including Andy Grewal, Seth Barrett Tillman and myself).

The government's brief demonstrates that many presidents, starting with George Washington, have retained major business interests while in office. Indeed, unlike Trump, they did not put these businesses in any kind of trust and retained direct management of them. They also owned them directly, unlike the hotels in question, which are owned by various subsidiaries of the Trump Organization.

Despite all this, none of these presidents - whose behavior established important precedents for the conduct of the office - took any steps to prevent doing business with foreign countries. At least one, George Washington, directly solicited such business, as I have demonstrated. Yet no one at the time even raised the possibility of an emoluments issue - and members of the Founding Generation were not shy about entering into constitutional arguments.

To be sure, the historical evidence does not affirmatively establish the scope of the Clause's prohibition, but it does show that presidents retaining active control of their business enterprises is not as obviously alarming as plaintiffs suggest. On the other hand, the plaintiffs simply have no evidence for their view of the Clause - that businesses owned by an officer of the United States cannot have even the most routine and minor business dealings with foreign countries, such as renting them hotel rooms. They can cite no cases or precedent. Indeed, President Barack Obama got a valuable, non-market emolument from the Norwegian Nobel Committee, a body appointed by the Norwegian Parliament.

One major problem with the plaintiffs' case is standing, a constitutional question, that unlike the Foreign Emoluments Clause, is far from novel or obscure. Some of the plaintiffs allege obviously general grievances with no possible basis for standing. But the most colorable standing claim in the CREW litigation is by some restaurant owners who claim they are losing business to Trump's restaurants. The government's brief does a good job of showing that these restaurants are not remotely competing in the same market.

But competitor standing is also the basis for a lawsuit brought this week by the District of Columbia and Maryland attorneys general. They claim Trump's hotel takes business from their public convention centers. But there is no indication that the convention services serve the same segment of the real estate market as Trump's high-end hotels.

In any case, there is a built-in tension between the substance of their claims and their standing arguments. On one hand, they claim Trump's hotels get business from foreign governments specifically because he is president - i.e., in some kind of attempt to curry favor with him. But if that is true, then the foreign governments will not simply shift their events to the Washington Convention Center if the plaintiffs win the Foreign Emoluments case. They would simply exit the market.

If, on the other hand, the foreigners really do need a room or event space - that is, an ordinary market transaction - then the plaintiff's Emoluments Clause argument is at its weakest.

Indeed, it is not clear that a publicly owned convention center is well-placed to make competitor standing arguments - it is not trying to make a profit, but to attract visitors to the District. And by their account, Trump is helping bring in foreign visitors.

Show Comments (0)