The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Law firm's use of potential target's name and logo in ad isn't 'trademark dilution'

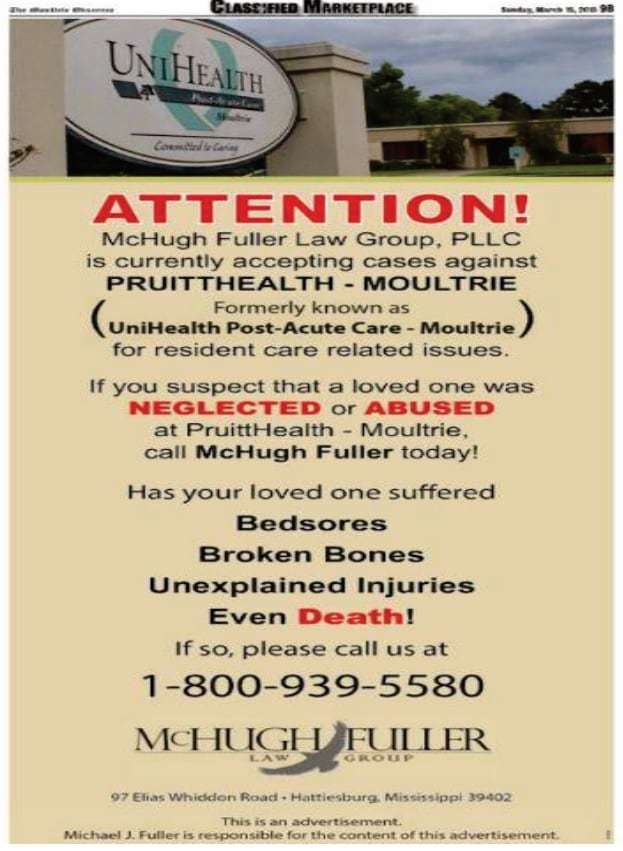

So the Georgia Supreme Court held Monday in McHugh Fuller Law Group, PLLC v. PruitHealth, Inc., I think quite correctly. McHugh Fuller, a firm that sues nursing homes, ran this ad in a local newspaper:

PruittHealth sued under a "trademark dilution" theory, claiming that the ad misused its name and logo. It didn't claim that customers would likely be misled into thinking that PruittHealth endorsed the ad (that's a more standard trademark claim, brought under a consumer confusion theory); rather, it claimed that McHugh Fuller's ad impermissibly diluted PruittHealth's trademark. But the court rejected the claim:

[Under the Georgia trademark dilution statute,] OCGA § 10-1-451 (b) …, actionable trademark dilution can take two forms:

The first is a "blurring" or "whittling down" of the distinctiveness of a mark. This can occur where the public sees the mark used widely on all kinds of products. The second type of dilution is tarnishment which occurs when a defendant uses the same or similar marks in a way that creates an undesirable, unwholesome, or unsavory mental association with the plaintiff's mark.

… At issue in this case is tarnishment, which OCGA § 10-1-451 (b) describes as "subsequent use by another of the same or any similar trademark, trade name, label, or form of advertisement" adopted and used by a person, association, or union "if there exists a likelihood of injury to business reputation … of the prior user, notwithstanding the absence of competition between the parties or of confusion as to the source of goods or services." This theory of liability "has had some success when defendant has used plaintiff's mark as a mark for clearly unwholesome or degrading goods or services." …

The selling power of a trademark … can be undermined by a use of the mark with goods or services such as illicit drugs or pornography that 'tarnish' the mark's image through inherently negative or unsavory associations, or with goods or services that produce a negative response when linked in the minds of prospective purchasers with the goods or services of the prior user, such as the use on insecticide of a trademark similar to one previously used by another on food products.

The basic idea is that "the consumer's distaste for the unsavory or inferior product has 'rubbed off' on the famous trademark, thereby damaging it."

However, not every unwelcome use of one's trademark in the advertising of another provides a basis for a tarnishment claim. Tarnishment can occur "only if the defendant uses the designation as its own trademark for its own goods or services." "[C]ases in which a defendant uses the plaintiff's mark to refer to the plaintiff in a context that harms the plaintiff's reputation are not properly treated as tarnishment cases." … "[E]xtension of the antidilution statutes to protect against damaging nontrademark uses raises substantial free speech issues and duplicates other potential remedies better suited to balance the relevant interests." …

Here, McHugh Fuller was advertising its legal services to individuals who suspect that their loved ones have been harmed by negligent or abusive nursing home services at a specific PruittHealth nursing home. The ad used PruittHealth's marks in a descriptive manner to identify the specific PruittHealth facility; indeed, McHugh Fuller was counting on the public to identify PruittHealth-Moultrie by the PruittHealth marks used in the ad.

The ad did not attempt to link PruittHealth's marks directly to McHugh Fuller's own goods or services. McHugh Fuller was advertising what it sells - legal services, which are neither unwholesome nor degrading - under its own trade name, service mark, and logo, each of which appears in the challenged ad. No one reading the ad reproduced above would think that McHugh Fuller was doing anything other than identifying a health care facility that the law firm was willing to sue over its treatment of patients. In short, the ad very clearly was an ad for a law firm and nothing more….

PruittHealth has cited no case analogous to this one to support its position. PruittHealth relies on Original Appalachian Artworks, but there a federal district court found tarnishment under Georgia's anti-dilution statute because the defendant's "Garbage Pail Kids" cards and stickers "derisively depict[ed] dolls with features similar to [the plaintiff's] Cabbage Patch Kids dolls in rude, violent and frequently noxious settings." PruittHealth also cites Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions, Inc., but there the district court found tarnishment under Georgia's anti-dilution statute because the defendant used Pillsbury's "Poppin' Fresh" and "Poppie Fresh" trade characters along with its trademark and jingle in a highly sexualized and "depraved context" in the magazine Screw. And in NBA Properties v. Untertainment Records LLC, the district court found tarnishment under federal and New York law where the defendant juxtaposed a distorted NBA logo containing the silhouetted basketball player with a gun in his right hand and the words "SPORTS, DRUGS, & ENTERTAINMENT." See also PepsiCo, Inc. v. #1 Wholesale, LLC (finding tarnishment under federal law and OCGA § 10-1-451 (b) where the defendants advertised and sold bottle, can, and food cannister safes for the concealment of illicit narcotics manufactured using plaintiff PepsiCo's products and bearing its famous Pepsi, Doritos, and other trademarks); Sandra L. Rierson, The Myth and Reality of Dilution, 11 Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 212, 247 n.125 (2012) (collecting additional cases where dilution by tarnishment has been found, all of which involve the defendant's association of a mark with sex or illegal drugs).

Contrary to PruittHealth's assertion in the trial court, trademark law does not impose a blanket prohibition on referencing a trademarked name in advertising. "Indeed, it is often virtually impossible to refer to a particular product for purposes of comparison, criticism, point of reference, or any other purpose without using the mark. Moreover, interpreting OCGA § 10-1-451 (b) expansively to prohibit the use of PruittHealth's marks to identify its facilities and services in any way, as the company urges, would raise profound First Amendment issues. "Much useful social and commercial discourse would be all but impossible if speakers were under threat of an infringement lawsuit every time they made reference to a person, company or product by using its trademark."

Accordingly, the trial court erred in entering the permanent injunction against McHugh Fuller based on OCGA § 10-1-451 (b). [Footnote: In light of this conclusion, we need not decide whether, as McHugh Fuller contends, OCGA § 10-1-451 (b) includes an implicit fair use defense like the express defense in the federal [trademark dilution statute].] If PruittHealth believes that McHugh Fuller's advertisements are untruthful or deceptive, the company must seek relief under some other statutory or common-law cause of action.

Show Comments (0)