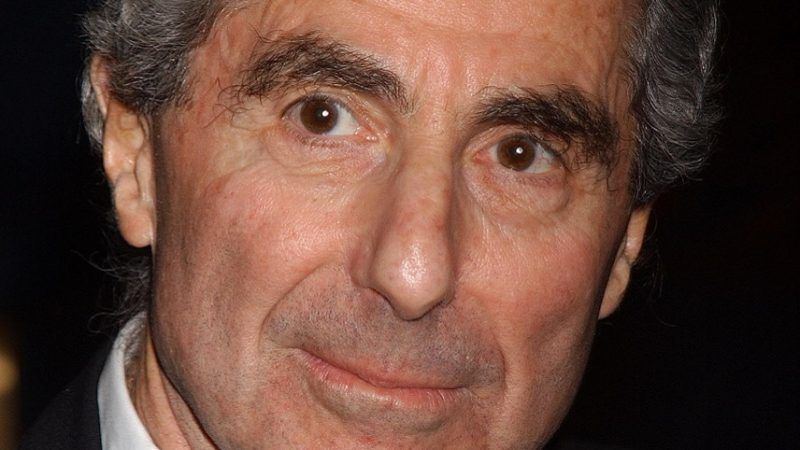

Philip Roth, RIP

If you are doing work that is expressive of what you believe and hope for, you need to "read" the arc of Philip Roth's career more than any of his individual titles.

Like a lot of people born at the very end of the Baby Boom, my first exposure to Philip Roth was not from his own books, but in the pages of Mad magazine. In the early '70s, it seemed like every issue had one of more gags related to Portnoy's Complaint, his best-selling novel in which the eponymous character describes masturbating with a piece of liver. A Mad anthology featured a parody of the film version Goodbye, Columbus, lazily titled Hoo Boy Columbus!, if I remember correctly. By the time I got around to reading that powerful short-story collection about Jewishness, class, and assimilation, I already knew all the key plot points of the titular novella.

With Roth's passing, an entire era of American letters closes up shop for good. Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1933, Roth came of age when being a novelist meant you could be or were even expected to be a culture hero, too. Especially if like him, you were partial to dropping turds in the cultural punch bowl or, like Norman Mailer or Gore Vidal, a raging narcissist who mistook the ability to write a sharp sentence for seriousness of thought on every topic du jour. Nowadays, our "great" writers are either pursuing trivial pursuits (Jonathan Franzen's most-heartfelt cause seems to be preserving bird habitat in Central Park) or toiling in relative anonymity, displaced by other forms of media, especially TV shows such as The Wire, The Sopranos, or Mad Men that do the cultural work once reserved for literature.

Along with Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud, Roth was part of the post-war Jewish triumvirate of ethnically and literarily serious novelists, what Bellow once called the "Hart, Schaffner, and Marx" of American letters (HSM was an upper-middle-class men's clothing brand back when such things mattered). Like other writers of his background (especially from Newark, which also birthed such unassimilable heroes as Milton Friedman and Leslie Fiedler), Roth could be deliberately and offensively Jewish even as he cultivated a Henry James shtick, consciously toggling between worlds stinking of gefilte fish and organ meats and made boring and tedious by reserved, WASPish decorum. He's certainly not the last American writer of Jewish heritage, but he may well be the last Yid. Roth's specific ethnicity (and that of other white ethnics who were Italian and Irish) just doesn't matter that much anymore. Everybody these days is an insider/outsider, the symbolic role played by many of his characters, and in a world of post-colonial identity politics and intersectionality, being Jewish, male, and first-generation college doesn't cut the mustard, Kosher or not. The same is true of his sexual fixations, especially in books such as Portnoy's Complaint. I was born 30 years after Roth but even by the time I started reading "serious" literature and entered grad school for English in the late 1980s, his sexual revolution seemed as distant to my times as that of the Founding Fathers.

So is there something we can take from his ouevre, his life, his example? The shelf of books, fiction and memoir, he wrote isn't just voluminous, it's groaning under the weight of great passages and deep insights into the human condition, if we still believe in such a quaint, universalistic notion. Even his sillier works, such as The Great American Novel, a satire of a fictional baseball league set during World War II, rewards perusal. He introduced Americans to "writers from the other Europe" in a series of books written by authors trapped behind the Iron Curtain or exiled from it (a conventional political liberal, he was a great American defender of free speech in all its forms).

Much more to the point than any single work of Roth's is the constant searching, seeking, and maturation he displayed throughout his career. In the wake of the Kitty Genovese murder, he wrote in 1961 that "we now live in an age in which the imagination of the novelist lies helpless before what he knows he will read in tomorrow morning's newspaper." Like many serious writers (well, at least many serious male writers, such as Thomas Pynchon, Robert Coover, and John Barth)—he retreated somewhat into writing about writing (so-called metafiction or surfiction) and broad satire. To his credit, he moved past that stage and, like Bob Dylan in music, created at least one work that "mattered" every few years until he hung up his spurs in 2012. Later works such as 1997's American Pastoral, 2000's The Human Stain, and especially 2004's The Plot Against America show a man trying to make sense of a world that he was raised to inherit but that had gone missing due to the vagaries of history. The Plot Against America is an alternative history in which Charles Lindbergh becomes an isolationist president in 1940; a savage if somewhat mistaken take on George W. Bush unilateralist foreign policy, it's far more relevant to Donald Trump's presidency.

"Lord have mercy on us, we want a 'great' writer," wrote Leslie Fiedler back in 1951.

It is at once the comedy and tragedy of 20th-century American letters that we simply cannot keep a full stock of contemporary "great novelists."…From moment to moment we have the feeling that certain claims…are secure, but even as we name them they shudder and fall.

Fiedler's humorous ire was directed at F. Scott Fitzgerald, who is U.S. literature's equivalent of a one-hit wonder (maybe one-and-a-half). But the charge is true of Roth's rough contemporaries, such as Thomas Pynchon, who stopped "mattering" shortly after the publication of Gravity's Rainbow over 40 years ago. Don DeLillo is younger than Roth, but close enough for comparison. After spending the 1970s and '80s writing books about terroristic violence, including one novel that ends with the destruction of the World Trade Center, DeLillo failed us all after 9/11 by taking years to write a minor work that escaped from Ground Zero as quickly as possible.

Roth, like Toni Morrison (born in 1931), kept at it, long and hard, trying to make sense of a world that escaped the conditions into which they were born. For all of us who expect to live long lives and who are doing work that isn't merely remunerative but expressive of what we believe and hope for, we need to "read" Philip Roth's career more than any of his individual books. Like all of us, he never fully transcended his roots even as he hacked at them ruthlessly, lovingly, and obsessively. He couldn't quite make it into a world that was post-racial, post-feminist, post-everything. But he kept trying, which is no small victory over the Conqueror Worm.

Show Comments (62)