Blame Binge Drinking for Tulane University's 2-in-5 Female Sexual Assault Rate

A survey reveals an unbelievably high sexual assault rate at one university campus.

Tulane University has a serious rape problem, if a recent survey can be believed: Nearly 2 in 5 female students reported being sexually assaulted. If that number is indeed real, the most likely culprit would be the university's binge-drinking problem.

Keep in mind that the infamous 1-in-5 statistic, which supposes that between a quarter and a fifth of female university students will become victims of sexual assault, is controversial; critics point out that the pollsters who arrived at this number often ask broad questions and count as victims people who never described themselves in such terms. Such high rates of sexual violence strike many people as self-evidently ludicrous.

But Tulane, a private university in New Orleans, appears to have an even more staggeringly high sexual assault rate. I've parsed the data and found no obvious flaws—sexual assault was defined fairly unambiguously as "unwanted sexual contact," "rape," or "attempted rape." Unwanted sexual contact was further defined as "fondling, kissing, or rubbing up against a person's private areas of their body (lips, breast/chest, crotch, or butt), or removing clothing without the person's consent by incapacitation or force." Without consent was further defined as "taking advantage of me when I was too drunk or out of it to stop what was happening."

What's more, the survey is extremely comprehensive: 47 percent of the school's students participated in it.

According to the survey, 41 percent of undergraduate female students experienced sexual assault while at Tulane. That includes off-campus violence, and it includes violence committed during breaks and holidays. Still, it's an incredibly high number.

For undergraduate men, the sexual assault rate was 18 percent. Sexual assault rates were significantly higher for LGBTQ men, 44 percent of whom experienced violence, compared with just 13 percent of straight men. Students of color were less likely to be victims than white students. In all cases, the perpetrators were overwhelmingly male students; the violence was just as likely to have occurred on campus as off.

What can explain these bafflingly high rates of sexual violence? The statistics relating to alcohol abuse on campus start to suggest an answer.

"Seventy-four percent (74%) of women and 87% of men who experienced any form of sexual assault reported they were incapacitated by alcohol at the time of the incident," according to the survey. Perpetrators were also more likely than not to be drinking alcohol, respondents said.

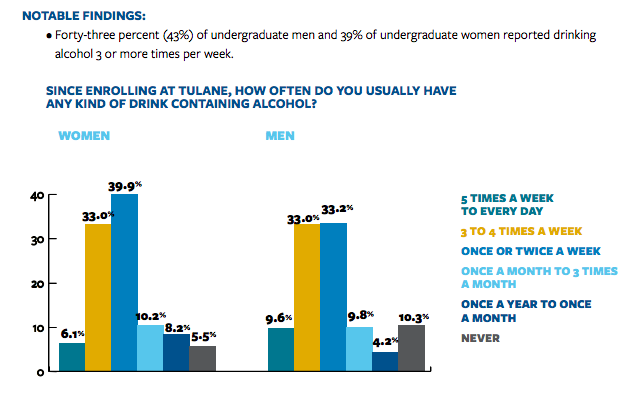

How many students were drinking, and how often? Quite a lot: 43 percent of undergraduate men and 39 percent of undergraduate women reported drinking alcohol three or more times each week. That's a whole lot of 18- to 20-year-olds drinking regularly.

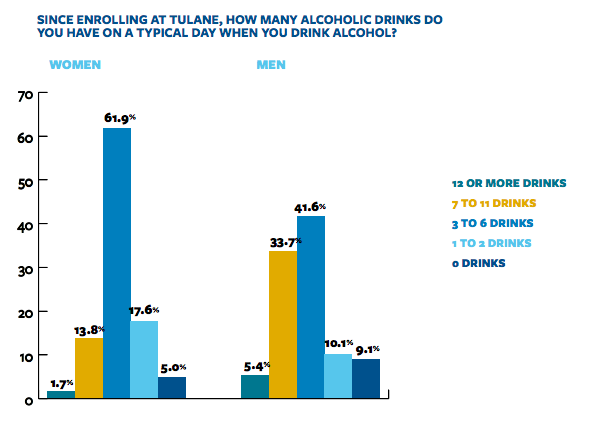

Their consumption levels were also telling. For women, the most common number of drinks to have in one sitting was between three and six. A third of the men were consuming between seven and 11 drinks.

To my mind, these numbers indicate a significant drinking problem: Many students, both male and female, are regularly and illicitly consuming copious quantities of alcohol.

A few things are worth bearing in mind.

First, a 120-pound woman who consumes more than three drinks in two hours is typically going to be very drunk. The same goes for a 180-pound man who consumes five drinks.

Second, most of these students are under the age of 21, and thus are not allowed to drink at all. They can't drink at bars, and they are less likely to consume alcohol in the presence of authority figures. They may not know their limits very well. They might not have much experience taking care of themselves, or other people, while under the influence.

Third, people who frequently drink to excess are taking risks, even of a non-sexual kind. Very drunk people impose obligations on others to take care of them. As Emily Yoffe said in the December Reason:

You cannot do something to someone else's body without their permission. But when you get incapacitated, you give up that integrity, because other people must take care of you.

You can walk off a roof, which has happened. You can choke on your vomit, which happens all the time. So you're turning yourself over to other people, and let's hope they're all guardian angels, but they're not always going to be. They could be bad people, or they could be fellow drunk people whose inhibitions are lowered, and you end up together, and potentially he does something criminal to you.

Yoffe and others who have pointed out the link between binge drinking and sexual assault are often derided as victim-blamers, and even now there's a profound reticence to make the obvious connection. When asked to comment on the survey's alcohol figures, Tulane President Michael Fitts told Washington Post readers, "It's very, very important to note that in no way, shape or form is this blaming or holding victims responsible. Alcohol is a tool of perpetrators."

But what if the campus would have fewer perpetrators if it had fewer abusive drinkers? The vast majority of sexually victimized students became victims while in a state of alcohol-induced incapacitation.

The current strategy—prohibition—clearly doesn't work. It would be for the best if local decision-makers at Tulane and elsewhere could experiment with some other approach, but because of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act, states must keep the drinking age at 21 if they want federal funds. But there's reason to believe that if teens could legally drink at an earlier age, they would encounter fewer alcohol-related campus pitfalls.

"If the drinking age were lower, it not only would move drinking out of unsupervised frat basements and into public, but might have a shot at changing our youth culture of excess, moving toward the European model of wine with dinner instead of crushing empty beer cans on one's head," Vanessa Grigoriadis writes in Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power, and Consent on Campus. "Lower the drinking age so that the psychological rush of trespassing, of engaging in binge-drinking culture because illegality is exciting, is deflated."