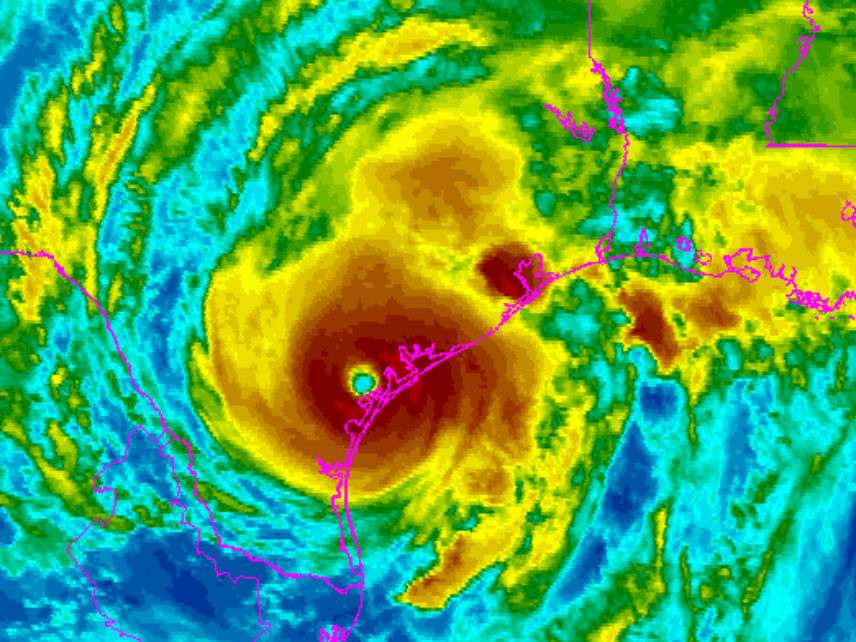

Hurricane Harvey and the National Flood Insurance Fiasco

Don't build in flood plains, and especially don't rebuild in flood plains

Texans, watch out. An aftershock is following behind the catastrophic flooding produced by Hurricane Harvey in coastal Texas: The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is coming up for reauthorization.

The main lesson that the public and policymakers ought to learn from Harvey is: Don't build in flood plains, and especially don't rebuild in flood plains. Unfortunately, the flood insurance program teaches the exact opposite lesson, selling subsidized insurance whose premiums do not come close to covering the risks home and business owners in flood prone areas face.

As a result, the NFIP is currently $25 billion in debt.

Federally subsidized flood insurance represents a moral hazard, Kevin Starbuck, Assistant City Manager and former Emergency Management Coordinator for the City of Amarillo, argues, because it encourages people to take on more risk because taxpayers bear the cost of those hazards.

Federal Emergency Management Agency data shows that from 1978 through 2015, 3.8 percent of flood insurance policyholders have filed repetitively for losses that account for a disproportionate 35.5 percent of flood loss claims and 30.5 percent of claim payments, Starbuck says. Most of these properties were grandfathered in before the NFIP issued its flood insurance rate maps. The NFIP is not permitted to refuse them insurance or charge them rates based on the actual risks they face.

Clearly, taxpayers should not be required to subsidize people who choose to build and live on flood plains. When Congress reauthorizes the NFIP, it should initiate a phase-in of charging grandfathered properties premiums commensurate with their risks. This will likely lower the market values of affected homes and businesses and thus send a strong signal to others to avoid building and living in such risky areas.

To avoid the problem of moral hazard, folks who choose to live in flood prone areas should bear the costs of the risks they face. After Hurricane Ike hit Galveston and Houston in 2008 causing $29 billion in damages, business and government leaders suggested building the "Ike Dike" along the coast to protect against future hurricane storm surges. One estimate puts the cost of building the dike's sand-covered dunes with hardened cores at $5 billion. Of course, proponents expected the federal government would pay for most of the dike's construction costs.

Congress is unlikely to unravel the flood insurance mess by the end of next month, but there are some lessons from recent weather disasters that lawmakers should take into account. If cities like Houston and Galveston need new and better coastal and flood defenses, then their citizens should pay for them.

If Texans living in flood prone areas refuse to tax themselves enough to protect themselves and their property that means that it doesn't make economic sense to live and work there. One proof of the adequacy of their coastal and flood defenses would be the willingness of private insurers to offer flood policies to residents. The same logic applies to all coastal counties. Ultimately, ending flood insurance subsidies will reduce property losses and put fewer lives at risk.

Show Comments (111)