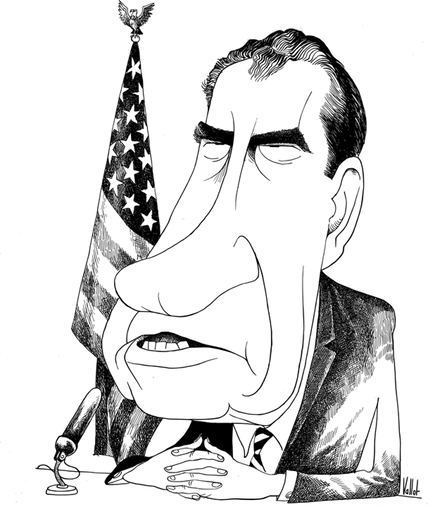

3 Ways We're Reliving the Watergate Culture War

The second time as farce

Whether or not we're reliving the Watergate investigation, we sure do seem intent on reenacting the Watergate culture war. That isn't just true of Donald Trump's critics, who are understandably eager to compare the 37th and 45th presidents. It's true of Trump and his team, who keep echoing arguments offered by Richard Nixon and his defenders four decades ago:

1. The double-standard defense. Complain about something Trump has done, and someone is bound to ask why you didn't say a peep when Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama did some other bad thing. (You will get this response even if you protested Clinton or Obama's action quite loudly.) The most prominent person to talk like this, of course, is Donald Trump himself:

With all of the illegal acts that took place in the Clinton campaign & Obama Administration, there was never a special counsel appointed!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 18, 2017

But this defense is a lot older than the present president's political career. Throughout the Watergate investigation, Nixon complained angrily that his predecessors had gotten away with the very activities that were getting him in trouble. In his 2003 book Nixon's Shadow, the Rutgers historian David Greenberg lays out some examples:

"If I were a liberal," [Nixon] told [die-hard defender Baruch Korff], "Watergate would be a blip." He compiled a private catalogue of behaviors by others that he believed excused his own. On the basis of comments J. Edgar Hoover made to him, he frequently claimed, not quite accurately, that Lyndon Johnson had bugged his campaign plane in 1968. When Nixon was chided for spying on political opponents, he shot back that John and Robert Kennedy had done the same. And as precedents for his 1972 program of political sabotage, he regularly cited the pranks of Democratic operative Dick Tuck, who had hounded Nixon since his 1950 Senate race. During the Watergate Hearings, [White House Chief of Staff H.R.] Haldeman testified that "dirty tricks" maestro Donald Segretti was hired to be a "Dick Tuck for our side."

There's more—much more—but you get the idea.

Now, Nixon may have gotten his facts a little scrambled when it came to that alleged airplane bug, and some of the supposed precursors to his crimes didn't actually fit the bill. (He seemed convinced that Daniel Ellsberg's leak of the Pentagon Papers was comparable to the Watergate break-in—a bizarre analogy, though if you've been following the debates over Edward Snowden you've probably heard worse.) But broadly speaking, the president had a point. Many American leaders had abused their powers, sometimes in ways that resembled the Nixon scandals, and the press hadn't always been quick to trumpet the news. Like Nixon, JFK had wiretapped reporters and used the IRS as a political weapon. LBJ may not have bugged Nixon's plane in 1968, but he did spy on Goldwater in 1964. And both Kennedy and Johnson, like many others who have held their job, presided over enormous violations of dissenters' civil liberties. You can make a decent case that Nixon's misbehavior was even worse than theirs, but you can see how the man could get a little resentful about the uneven attention.

The trouble with the double-standard defense is that it isn't much of a defense. The crimes of prior presidents aren't a reason to let Nixon off the hook; they're a reason to rein in not just one abusive president but the whole imperial presidency. The same goes for any Trumpian abuses today.

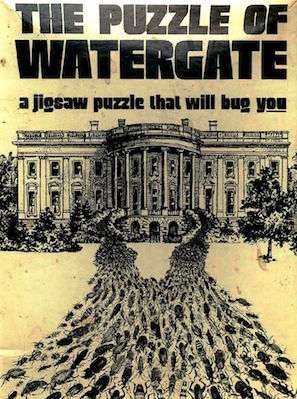

2. Intimations of a "coup." Then as now, each side accused the other of plotting a coup. Rumors that Nixon was planning to seize dictatorial powers circulated not just on the political fringes but in official Washington; many of the president's foes feared that fascism was on the way. After Nixon had Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox fired, Rep. Parren Mitchell of Maryland asked, "Will democracy as we have known it survive, or will fascism come to dominate in this country?" West Virginia Sen. Robert Byrd compared the move to a "Brownshirt operation."

Meanwhile, the president's defenders tried to write off the Watergate investigation as an attempt to invalidate the election. Some of them still do: Pat Buchanan, a Nixon staffer before he became a media star, marked the 25th anniversary of the break-in with a column calling Watergate "the overthrow of an elected president by a media and political elite he had routed in a 49-state landslide the like of which America had never seen." In more suspicious moments, Nixonites sometimes suggested that some deep-state force—Korff pointed his finger at "the unknown element of the CIA"—had orchestrated Nixon's troubles. (A few figures on the radical left agreed.)

Just as you don't have to think Nixon was a fascist to see the ways he undermined American liberties, you don't have to buy the whole Watergate-was-a-coup story to recognize that it contained at least a few grains of truth. To give the most obvious example, the most famous leaker of the Watergate era, the Washington Post source known as "Deep Throat," was eventually revealed to be Deputy FBI Director Mark Felt. He wasn't trying to overthrow the president, though—he was hoping Nixon would blame Felt's boss for the leaks and make Felt FBI director. (If he'd succeeded, that would've been a different sort of coup.)

Both the Watergate cover-up and the Watergate investigation took place against a backdrop of backroom warfare, with maneuvers so complex that even now historians can't always agree what everyone's motives were. Then as now, leakers don't always have noble motives; then as now, an ignoble motive can reveal a real story.

3. Drinking liberal tears. If you spend any time in ornery right-wing circles, you've probably heard some version of this one:

Fmr Kasich Supporter: Hostile Media Makes Me Support Trump https://t.co/LgsCXS23Vo

— Fox News (@FoxNews) May 14, 2017

The extent of that sentiment can be overblown, but it certainly exists. And it's a Nixon rerun too.

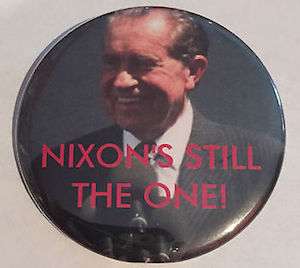

The president bled supporters as more facts about Watergate came out. But some conservatives who'd never been particularly pro-Nixon—men who'd had harsh words for his economic and foreign policies—started warming to him once they saw the hated Eastern Establishment trying to take him down. Looking back from 2005, M. Stanton Evans recalled that he "didn't like Nixon until Watergate." The writer who best represented this tendency may be Manchester Union Leader publisher William Loeb, who once had supported the president's resignation "simply because of what we regard as Mr. Nixon's incompetence." In 1973 he reversed himself, declaring that a White House exit "would be a complete surrender to hysteria deliberately created by the communications industry, which in its most important segment is monolithic in its hatred of President Nixon."

It wasn't just former #NeverNixon types who stood by the president. When you look back now at Nixon's final months in office, you might get the impression that hardly anybody liked him at the end. But even when his approval rating fell below 30 percent—an abysmal place for any politician's popularity—basic math will tell you that he still had millions of fans. Many of them loved him for having the right enemies. Some held demonstrations, where the press sometimes found themselves at the receiving end of taunts like those heard at Trump rallies today. At one pro-Nixon protest organized by Korff, Greenberg recounts, "a mob circled the reporters and demanded they transcribe the rabbi's words verbatim."

By May of 1974, one New York Times reporter believed that "this ad hoc movement may be the strongest force President Nixon has going for him." Granted, that was a low bar to clear. "Most of the Presidential Cabinet," the Times' John Herber wrote,

has fallen silent about Watergate. Members of Congress who have been stanch Nixon supporters are saying little in behalf of the President in their speeches across the country. In much of the executive branch, the officials who run the Government are indifferent to Mr. Nixon's future, leaving the impression that they would not mind seeing the Presidency pass into other hands.

The grass-roots Nixon movement, however, is aggressive, highly partisan and loyal. When release of the Watergate transcripts showed President Nixon to be losing conservative support in the media, in Congress and in the Republican party because of shock at their contents, several leaders of the petition movement about the country said their donations and memberships rose sharply.

Herber added that the die-hards harbored "a uniform distrust of the national news media." ("They think we are stupid and we can't think for ourselves," one told him. "I can no longer watch the newscasts for fear of having a severe case of apoplexy," declared another.) Remember that the next time someone points to a hardcore Trump fan shouting "FAKE NEWS!" and declares that we've entered some sort of internet-induced "post-truth era." All that hand-wringing may be a mite bit overwrought.

Speaking of overwrought: Remember Trump's declaration last week that "no politician in history, and I say this with great surety, has been treated worse or more unfairly" than he? Even that was an echo—Nixon once proclaimed himself the target of "the dirtiest, most libelous, slanderous attack on the president in the history of American politics." Of course, Nixon was speaking in a private White House bull session; Trump did his venting in a speech to graduating Coast Guard cadets. You know what they say: the second time as farce.

Show Comments (151)