The Political Class May Be Polarized, But That Doesn't Mean the Rest of America Is Too

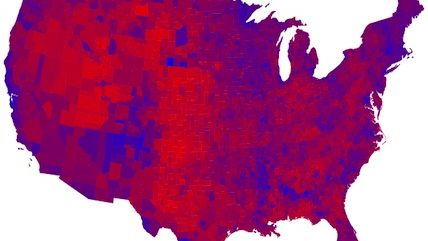

The myth of the Red/Blue nation

We are constantly told that America is not merely a divided nation but a nation whose divisions have split us into two big tribes, one colored red and one colored blue. The Stanford political scientist Morris Fiorina has spent years undermining that simplistic portrait of the country; in a new paper for the Hoover Institution, he reviews the research and reveals a far more complicated picture. Here are five lessons he draws:

1. The political class really is getting more polarized…

If you limit its scope to elected officials and professional activists, the polarization thesis has some truth to it. Since the early '70s, the parties have gone through a sorting process, to the point where the most left-wing Republican in either house of Congress is now more conservative than the most right-wing congressional Democrat. With a few exceptions, a similar trend can be seen in state legislatures. (*) Surveys show that party activists have gone through a similar process. So have political donors. In all these cases, Fiorina reports, the data "capture our intuitive understanding of the concept of polarization: the middle loses to the extremes."

2. …but the general public has not followed suit.

The class described in point #1 represents about 15 percent of the country. Things look different, Fiorina writes, when you look at "the rest of the electorate, whom I will refer to as normal people."

Over the last four decades, there has been little change in how Americans describe themselves ideologically—the most popular category in such surveys is still "moderate," without a big exodus to the liberal and conservative poles. Opinions have shifted on some specific topics, but not always in the same direction: Americans have gotten more liberal on certain issues, such as health insurance, and more conservative on others, such as aid to minorities. (Fiorina doesn't mention it, but on some issues the very definitions of the "liberal" and "conservative" positions haven't been stable.) Meanwhile, even as the parties have sorted, much of the public has at least symbolically resisted the sorting: The number of Americans identifying themselves as "independents" has increased considerably over the same period.

3. The more politically active you are, the less well-informed you are about these trends in grassroots opinion.

Both normal Americans and the political class tend to exaggerate the extent that the general public is polarized. But the politicos do much more of this, projecting their divisions onto the electorate at large. "Ironically," Fiorina writes, "the great majority of Americans whose lives do not revolve around politics are more accurate in their political perceptions than their more politically involved compatriots."

4. The stronger your partisan affiliations, the more likely you are to misconstrue what life is like at the other end of spectrum…

Fiorina shows this in several ways, but this is my favorite illustration:

Democrats think that 44 percent of Republicans make more than $250,000 per year, when the actual percentage is 2, and that 44 percent of Republicans are senior citizens, when the actual percentage is 21. For their part, Republicans think that 36 percent of Democrats are atheists or agnostics, when the actual percentage is about 9, and that 38 percent of Democrats are LGBT, when the true percentage is about 6. Once again, the more politically involved the respondent, the greater the misperception. The tendency of political media to highlight the most colorful and controversial personalities in the two parties ("exempli?cation") likely contributes to this state of extreme misperception….The very vocal and visible activist groups who shape the parties' agendas are another likely contributor.

5. …but that doesn't mean we're retreating into smaller bubbles.

There's a popular notion that Americans in the cable/internet era are sliding into parallel partisan universes. That isn't easy to reconcile with the idea that most Americans are not getting more partisan, and Fiorina cites several studies that throw cold water on the idea. A paper on Twitter users, for example, found that "Twitter networks tend to be fairly heterogeneous politically, in part because many of those in them are connected by only 'weak ties.' Contrary to the fears expressed by those worried about ideological segregation, social media actually may lessen people's tendency to live in echo chambers."

The portrait that emerges is one where most Americans mix their opinions more messily than their elected representatives do, refrain from relying on Fox- or MSNBC-style sources for their news, and do not put their political opinions first when forging their personal or collective identities. Adjust your tribal maps accordingly.

(* Fiorina mentions four states whose governments have not been getting more ideologically polarized: Louisiana, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and West Virginia. Noting that "some of the least polarized legislatures have a reputation for petty corruption," he speculates that "legislators who are skimming o? the top are more likely to make bipartisan deals to keep the gravy train running smoothly.")

Show Comments (170)