How The Hunting Ground Spreads Myths About Campus Rape

Activist film set to air on CNN this weekend uncritically parrots bad theories peddled by a serial exaggerator.

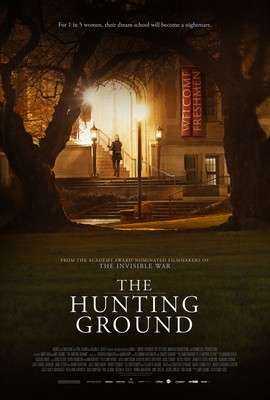

On Sunday night, CNN will air The Hunting Ground—a work of activist propaganda disguised as a documentary about sexual assault on American college campuses.

Among its numerous faults, the film blames the campus rape problem on a plague of serial rapists; expert opinion on this matter comes courtesy of psychologist David Lisak, whose misleading interpretation of his flawed research on serial predators is given center stage throughout the film. (Read Reason's multi-part expose on the research underlying Lisak's dubious theory here, here, and here, and see Linda M. LeFauve's new article examining Lisak's misleadingly constructed video interview with a rapist here.)

The Hunting Ground covers two high-profile sexual assault disputes in great detail. It goes to extraordinary lengths to paint the alleged assailants in these cases as perfect examples of Lisak's model rapist, implying that these men are repeat offenders who plan out their crimes and drug their victims.

But in reality, it's far from clear that The Hunting Ground's accused rapists are even actually guilty—let alone serial sociopaths who stalk and incapacitate their victims.

The "Amazing Lie at the Heart of a Movie Claiming to be a Documentary"

Nineteen Harvard University law professors have denounced the film for (among other faults) misrepresenting the case of Harvard law student Brandon Winston, whose life was put on hold after a night of drunken, drug-fueled sexual contact resulted in his expulsion from the university and criminal charges.

"What our student did is not the kind of violent, repeat sexual assault that the movie claims is both the nature of the problem nationwide and that each of the people in the film are an example of that," said Elizabeth Batholet, one of the Harvard law professors speaking out about The Hunting Ground's errors, in an interview with Reason. "That's an amazing lie at the heart of a movie claiming to be a documentary."

Winston was accused of sexual misconduct by then-student Kamilah Willingham, who gives her one-sided account of the dispute toward the beginning of The Hunting Ground. According to Willingham, she and a female friend had drinks with Winston at her apartment, proceeded to a bar where Winston bought them more drinks, and then all three returned to her apartment in a state of inebriation, where Winston assaulted them while they slept. The clear implication from the film is that Winston is a monster frequently preys on his victims by drugging them and was ultimately able to elude justice because Harvard does not take victims seriously.

"He's a predator," Willingham says in the film "He's dangerous."

But, as Slate's Emily Yoffe discovered in her groundbreaking investigation of the dispute earlier this year, the real story was much different. There is no evidence that Winston drugged the women; on the contrary, Willingham and Winston both consumed cocaine that Willingham herself had supplied. Willingham used a bloody condom she discovered in her wastebasket as evidence that her friend had been violently raped, but DNA evidence ruled out the possibility that the condom had been used by Winston (though it did match Willingham).

Nor is it true that Winston escaped wholly unpunished, as The Hunting Ground implies. Harvard initially recommended his expulsion, and repeatedly placed him on academic leave, but reinstated him after determining that insufficient evidence existed to brand the encounter as assault. A grand jury declined to indict him on any charges having to do with Willingham; he was eventually convicted of a misdemeanor charge of nonsexual touching of Willingham's friend. The film's only reference to these facts is through some text briefly displayed at the very end.

The accusation put Winston's future on hold for three years. A young black man with no history of criminal activity had to suspend a promising education at Harvard law school while both university administrators and the court system adjudicated the accusations against him.

"Three good years of his life have gone solely to this," said Harvard Law Professor Janet Halley, who also rejects The Hunting Ground's narrative, in an interview with Reason. "It's not right for the filmmakers to extend it out to yet another trial in the court of public opinion, when the underlying claims have been so conclusively rejected. It's bad for the overall effort for justice, and it's bad for this young man."

"Major Distortions and Glaring Omissions"

The Hunting Ground's case against former Florida State University star quarterback Jameis Winston (now with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers; no relation to Brandon Winston) is similarly plagued by inaccuracies. Accuser Erica Kinsman claimed Winston drugged her at a bar, forced her back to his apartment, and raped her on the bathroom floor.

Kinsman says in the film that she's "fairly certain" the drink Winston (or one of his friends) gave her was spiked, but two separate toxicology reports established that there were no date-rape drugs in her system on the night of the incident. Indeed, Kinsman has repeatedly changed the details of her story, first saying she passed out after consuming the drink and was unable to recall how she got into a car with Winston, and later saying she was coerced or intimidated into the car (something investigators thought was dubious, given that there were a lot of other people around at the time). The facts undermine the idea that she was preyed on by Winston, who was eventually cleared of sexual assault during a university hearing run by a retired Florida Supreme Court justice. Winston is now suing Kinsman for defamation.

In a statement chiding CNN for deciding to screen The Hunting Ground, FSU President John Thrasher excoriated the film for its "major distortions and glaring omissions." Its producers have fallen into the same trap as Rolling Stone's editors did with their discredited story about gang rape at the University of Virginia, wrote Thrasher.

"A Film Project That Is Very Much in the Corner of Advocacy"

The makers of The Hunting Ground, of course, are not interested in anything resembling the truth. Indeed, an email from investigative producer Amy Herdy made public confirmed recently this beyond any doubt. In the email, Herdy told Kinsman's lawyer that the makers of The Hunting Ground, "do not operate the same way as journalists—this is a film project that is very much in the corner of advocacy for victims, so there would be no insensitive questions or the need to get the perpetrator's side." In a separate email, Herdy discusses tactics for "ambushing" Jameis Winston.

While the cases against the two Winstons don't stand up to scrutiny, The Hunting Ground does manage to identify a single serial predator: an unnamed man whose face is blurred for his interview with the filmmakers. This man confesses that he was incarcerated for sexual assault and hopes that by coming forward, he is educating the public about how to prevent people like him from committing attacks. His monologue is interspersed with separate commentary from Lisak. Here is a transcript of that part of the film:

Man: "I was incarcerated for six and a half years for sexual assault. I know I was at fault. Like I said, the reason I really wanted to do this interview was to help someone else out. Maybe to have them become aware of what they are doing wrong."

Lisak: "The really practiced sex offenders identify groups of people who are more vulnerable."

Man: "College is the place where lots of alcohol is consumed and the number of victims is endless."

Lisak: "These men select victims ahead of time. It could be a bar, it could be a fraternity party where people are drinking."

Man: "At the parties, like frat parties, I mean people are getting wasted. So it's not like a lot of the time dependent on who they're with. Nobody keeps an eye on them."

Lisak: "The alcohol is essentially a weapon that is used to render somebody extremely vulnerable."

Man: "Alcohol definitely makes it easier to overpower a victim if they're inebriated or under the influence. Less struggle for sure."

Lisak: "Then there is an isolation phase. So if somebody who has deliberately gotten this young woman extremely intoxicated, and at some point he says to her, 'I'll walk you back to your room,' or 'you can sleep it off if you want, we have a bed upstairs.' And that's where the assault occurs."

The film's only case of clear-cut predation, then, is supported exclusively by an anonymous interview that provides no checkable details.

The film also claims eight percent of men in college commit 90 percent of the assaults and that the average number of assaults per rapist is six. The citation, of course, belongs to Lisak's 2002 study, "Repeat Rape and Multiple Offending Among Undetected Rapists." But as Reason confirmed in its previous invesitgations of Lisak's work—and Lisak himself confirmed—that study wasn't actually about college students, and didn't ask participants about crimes committed on campuses.

A Representative Case?

Is The Hunting Ground's anonymous predator—whose crimes are implied, but not confirmed, to have taken place on a campus—a representative case?

The interview bears a striking similarity to one conducted by Lisak decade ago. Lisak allegedly sat down with a serial rapist who was also fraternity brother and interviewed him about is methods. This conversation was later replicated by an actor and passed off as an anti-rape educational material dubbed an interview with an undetected rapist, and known as "the Frank video."

But, as a new investigation by Reason contributor Linda LeFauve reveals, the Frank video is a composite of several conversations with rapists—demonstrating that Lisak's own stereotypical serial predator is a carefully concocted cut-and-paste character.

The validity of Lisak's theory was recently called into question by a new paper authored by Kevin Swartout, Mary Koss, Jacquelyn White, Martie Thompson, Antonia Abbey, and Alexandra Bellis. The authors found the serial predator theory to be based on "surprisingly limited" scientific evidence; their own study that most college rapists did not commit rapes across multiple years.

Lisak and his advocates have pushed back against this study, telling The Huffington Post that it contains significant flaws and ought to be retracted.

Nevertheless, Swartout said in an email to Reason that his team stands behind their work.

"We want to move the field forward by engaging in discussion of the issues through the peer review process," he said.

Co-author Mary Koss told Reason that "no study is above reproach and we were and are open to constructive criticism and the need to make corrections if deemed necessary in the judgment of the editors."

The science behind the serial predator theory, then, remains decidedly unsettled. But people who tune in to CNN on Sunday night won't be treated to a nuanced examination of the question. Instead, they will be hit with a work of activist propaganda that wrongfully portrays college campuses as uniquely dangerous environments where women are literally hunted by sociopathic rapists.

"We who have spoken out at Harvard are completely committed to addressing sexual assault," said Bartholet. "It's horrible that this film is coming out that is now misrepresenting the nature of the problem and diverting attention away from how we can address it."

Show Comments (66)