Mushrooms Aren't Magic

This article is part of Reason's special Burn After Reading issue, where we offer how-tos, personal stories, and guides for all kinds of activities that can and do happen at the borders of legally permissible behavior. Subscribe Now to get future issues of Reason magazine delivered to your mailbox!

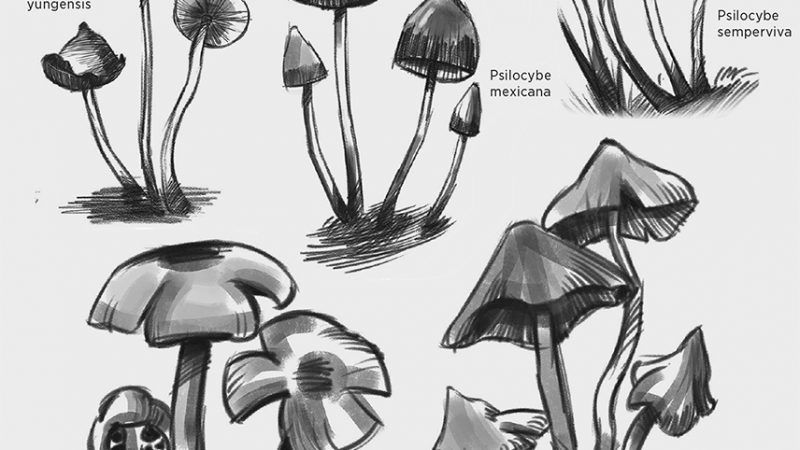

When Spanish Catholics subjugated the Mesoamericans, they eradicated a religion but not its chief sacrament. Psilocybin mushrooms continued to grow throughout Central America and to clandestinely fuel the trips of indigenous psychonauts. In the 1950s, the Mazatec shaman María Sabina led an American banker named Gordon Wasson and his wife in a mushroom ceremony, and the couple returned to the U.S. as proselytizers. Today, psilocybin mushrooms are more popular and easier to cultivate than at any point in recent memory, thanks to the internet's ability to disperse knowledge in much the same way that Psilocybe mexicana spreads its spores.

But it wasn't always so. The first widely available American treatise on home growing was 1976's Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide. Authors Terence and Dennis McKenna published under the pseudonyms O.T. Oss and O.N. Oeric, though in a fun twist, Terence wrote the forward under his real name. In addition to trippy illustrations juxtaposed with chemical diagrams and laboratory photos, the brothers provided detailed instructions for achieving the four major stages of growth: extracting spores (the fungal equivalent of seeds), cultivating a batch of mycelium (the vegetative part of a fungus), inoculating a sterile medium with the mycelium, and then simulating the conditions of a humid forest floor in order to produce mushrooms.

Forty years later, the book is useful mostly as a window into Terence McKenna's imagination. "I am old, older than thought in your species," he envisions a mushroom saying to a human. "By means impossible to explain because of certain misconceptions in your model of reality all my mycelial networks in the galaxy are in hyperlight communication across space and time." The actual growing advice, however, is archaically complex (see: using agar, a growing medium common in labs but unnecessarily complicated for home mycologists).

Several decades of experimentation and knowledge sharing have led to a much simpler orthodoxy, with most amateur mycologists now of one opinion about the best materials and methods. For beginners, an internet search for "PF Tek" will return a nearly foolproof method for growing small amounts of Psilocybe cubensis at home. (It will also point you to forums where every question you can possibly imagine has been answered in great detail.) All the materials can be purchased at your local hardware and health food stores, save one: the actual spores.

Psilocybin spores are legal to possess for microscopy purposes in all but three states (Georgia, Idaho, and California do not allow their possession for any reason). They can be ordered, along with microscope slides, from vendors such as Spore Works. But the minute you attempt to cultivate them, you will be breaking the law.

Here I should note that the instructions are nearly, but not entirely, foolproof. Growing any type of mushroom—culinary, medicinal, or magic—is a challenge for even the greenest thumb. Paul Stamets, America's premier populizer of citizen mycology, writes in his 2005 book Mycelium Running that success at growing mushrooms relies on a number of factors, "some obvious and some mysterious." Nobody talks this way about growing cilantro in a kitchen window sill.

That's because plants need only sunlight, water, soil, and to not be forgotten about entirely, while mushrooms require parenting. Most plants are no worse for wear if you accidentally ash a cigarette on their heads or leave town for a long weekend and don't water them. You will find them sickly and resentful-looking when you get back, but wet their roots and they'll forgive you. Not mushrooms. A single misstep early on will kill your experiment dead in its tracks. One day, your babies will be reaching their delicate hyphae through a seemingly sterile substrate; the next they'll be hampered by green patches of Trichoderma and cottony tufts of cobweb mold.

In fact, your mushrooms may falter even if you do everything right, which probably seems like a paradox: How can it be so hard to grow them in the relatively sterile confines of a temperature-controlled home, yet so easy to find them bursting out of piles of cow shit?

It helps to think of mushroom cultivation as microscopic world building rather than plant growing. If you prepare a clay pot for a seedling and place it on a window sill inside your home but never actually plant anything, you can reasonably expect the pot to remain barren indefinitely. When you make a good home for mycelium, however, you've made a damp, welcoming environment for all manner of tiny, invisible, and invasive travelers. Do nothing with that container, and unwelcome life will eventually find a way there, just as it does on a forgotten piece of sharp cheddar in the back of your fridge.

One must make peace with failure—initially but also throughout one's mycological journey. There's only so much you can do to aid Psilocybe cubensis in its efforts to reproduce (for that is all mushrooms are to mycelium: a vehicle for spreading spores). Competing species of fungus and bacteria also want to pass along their genetic material and will fight valiantly to do so. Practicing good hygiene, following instructions, and taking notes will give your preferred species a leg up, but ultimately you can only watch and hope that the genes you're cheering are both selfish and strong.

Even the most meticulous mycologist will fail at some point, probably repeatedly. But every embryological stage you get to witness, even if it does not culminate in fruiting, will fill you with wonder. That first vein of mycelium, creeping along the glass wall of a Ball jar, will be to you as veins of gold were for western prospectors. Watching it search out other patches of mycelium to form a network will have you marveling at the miracle of life. The rich, sweet, earthy smell of the budding fungus—be it Psilocybe cyanescens or Pleurotus ostreatus, a delicious oyster mushroom—will be more fragrant to you than the finest myrrh. Should you bear witness to primordium protruding from a mycelial mat, you will want to shout from the rooftops. And if you are so lucky as to taste the literal fruit of your efforts, you will be forever different because of it.

Your friends will think you're weird. But you will know something they don't about how life happens on this wonderful planet. And if you approach your experience with the right mindset and in the right setting, you will learn why the Mesoamericans called psilocybin the "food of the gods."

Don't forget to check out the rest of Reason's Burn After Reading content.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Mushrooms Aren't Magic."

Show Comments (1)