The Radical Freedom of Dungeons & Dragons

Four decades after its creation, Gary Gygax's fantasy world of unbounded choice is more appealing than ever.

You might not recognize the name Gary Gygax. But even if you've never rolled a critical fail on a d20, you have almost certainly consumed some movie, TV show, book, comic, computer game, or music influenced by Gygax's most famous creation: Dungeons & Dragons, the world's first and most popular role-playing game.

The FBI certainly knew who he was. Between 1980 and 1995, agents compiled a dossier on the gaming company TSR Inc. and Gygax, its founder. In 1980, a note on TSR stationary about an assassination plot drew the FBI's attention, leading to a search of the company's offices in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The note turned out to be materials for an upcoming espionage game.

In 1983, an FBI field report about an investigation into a cocaine trafficking ring in Lake Geneva cryptically references Gygax—but whatever his alleged role was, it has since been heavily redacted by the Bureau.

The company appears again in FBI reports from 1995, as part of the agency's sprawling investigation into the Unabomber. The FBI was apparently looking into a possible tie between the string of then-unsolved bombings and a bitter legal dispute between TSR and a rival gaming company in Fresno, California.

In an FBI field report describing the convoluted history of TSR, one source at the company describes the father of role-playing games as "eccentric and frightening," a "drug abuser" who is "known to carry a weapon and was proud of his record of personally answering any letter coming from a prisoner." He would be extremely uncooperative if the FBI tried to interview him, the source warned.

The report also claims Gygax set up a Liberian holding company to avoid paying taxes and "is known to be a member of the Libertarian Party."

The FBI's source could have been any number of professional and personal enemies Gygax made in the turbulent decade between the debut of Dungeons & Dragons in 1974 and his eventual ouster from the company—once one of the fastest-growing in the United States—as it foundered under mismanagement.

But D&D survived. Today, more than 40 years after its invention, it is experiencing a renaissance. The number of players is increasing, both at the traditional table and on the internet. On Virtual Grounds, a popular online gaming site, the number of D&D games rose 55 percent, from roughly 255,000 in 2016 to 395,000 in 2017. The game has moved out of the basement and into game nights at hip bars and pop-up cafés. One of the most popular podcasts of 2017, The Adventure Zone, features three brothers and their dad playing D&D. The game's strange dice are tossed behind prison walls and used as a learning tool for children on the autism spectrum. And it remains a refuge, as always, for nerds, theater kids, and other strange birds.

The latest supplementary rulebook for the game, Xanathar's Guide to Everything, cracked several bestseller lists when it was published in November. What is driving hordes of people to throw down good money to buy a narrative-free tome full of spell descriptions and rules about sleeping in armor?

The sinister-sounding allegations in Gygax's FBI dossier (obtained by Reason via a Freedom of Information Act request) hint at an explanation. It's not a surprise the game's creator was a self-declared libertarian or a proud pen pal of prison inmates. He was an individualist at heart who had always chafed against discipline. That perpetual inclination to seek out ever more possibilities—"why not?" rather than "why?"—is baked into D&D. The same thing that drew the ire of overheated evangelicals and parent groups is leading to the game's newfound popularity today.

D&D is a deeply libertarian game—not in a crude political sense or because its currency system is based on precious metals, but in its expansive and generous belief in its players' creative potential. It's collaborative, not competitive. It offers a framework of rules, but no victory condition and no end. The world you play in, and how you shape it, are entirely up to you.

In the afterword to the original D&D manuals, Gygax encouraged players to resist contacting him for clarification on rules and lore: "Why have us do any more of your imagining for you?"

'The Theater of the Mind'

It's the game's unboundedness that has seduced millions of people—children, teenagers, and adults—to sit around tables and essentially take part in highly codified games of make-believe.

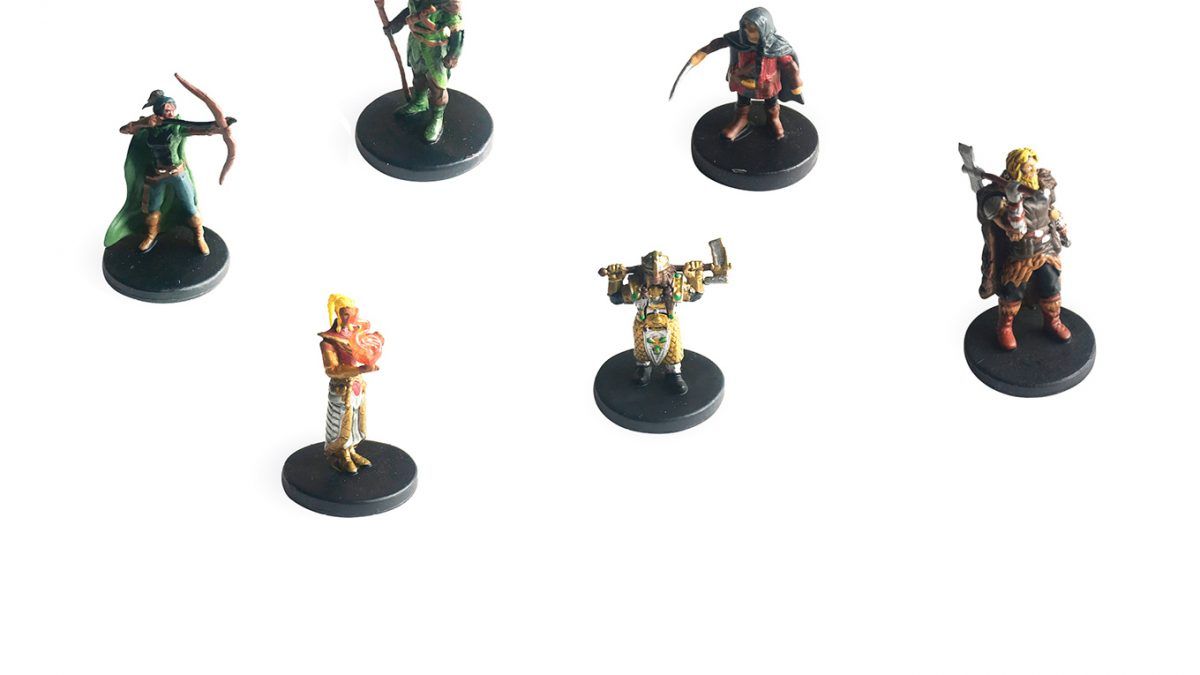

In D&D, each player becomes a character with a race (dwarf, say) and class (ranger, cleric) based on classic fantasy tropes. The objective is to quest for loot and fame—or justice and saving the world. Players work together to delve into dungeons and defeat baddies, gaining power and abilities as they go. If this premise sounds familiar to players of video games like Destiny or Skyrim, well, D&D invented it. The adventuring is run by a "dungeon master," or D.M., who adjudicates the rules and controls the monsters and non-player characters. The players tell the D.M. what they want to do, and the D.M. describes the results. If an action requires a special skill, the player rolls variously sized dice to see if he or she succeeds. Most of the action happens in the "theater of the mind," although map grids and miniature figurines can be used as visual aids.

In this way, D&D anticipated and solved the problem inherent in even the most exciting new video game. No matter how realistic the graphics, deep the gameplay, or big the map, at some point the seams start to show. The more a video game is played, the smaller the world feels.

D&D provides the opposite experience. At first, overwhelmed by the thick rulebooks and not used to flexing their imaginations, some new players have trouble grasping the full freedom it allows. The finest moments in D&D are when someone in the party figures out a solution to a problem that the dungeon master never prepared for, likely never even imagined. Working together is mandatory for success, but individual initiative gives every player a chance to shine.

What if, instead of just attacking the tribe of goblins raiding the caravan route, the party converted them to pacifism via religion? It's a strange, probably stupid idea, but there's an easy way to find out if it could work: make a pitch to the goblins, preferably with the aid of magic, and roll a "persuasion" check.

Because D&D is a cooperative game, it's an effective social lubricant, too. Strangers working together to accomplish a common goal soon become friends, and their exploits and foibles become shared memories. It's pure escapism, and when it works well and all the players buy in, the game is such an unvarnished, natural joy that it's hard to believe it hasn't always been around—that someone, somewhere had to invent it.

The Once and Future King

The son of a Swiss immigrant father, Ernest Gary Gygax was born in 1938 and spent his childhood doing the usual kid stuff: learning archaic words from dictionaries and exploring the tunnels underneath an abandoned insane asylum in the woods outside Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Though he was an avid reader, he found school terminally boring, according to Of Dice and Men (Scribner), a 2013 book recounting Gygax and TSR's history. He dropped out his junior year of high school and did a brief stint in the Marines before getting a medical discharge—likely a relief for both him and the Corps.

Gygax was working as an insurance underwriter at a firm in Chicago when Avalon Hill Games Inc. published Gettysburg, the first commercially available war game in the United States, in 1958. Players moved cardboard chits representing army units around a huge battle map. Combat and other actions were resolved through complicated rules involving tape measures, protractors, and lengthy debates. Many games adopted a neutral referee to pore over the rules and settle arguments.

It was about as niche as niche hobbies got. One had to have an enormous amount of spare time, a passion for rules, and a love of historical accuracy to derive any enjoyment from it. That made it the province of teenagers, college dorm shut-ins, and garrulous middle-aged men. People who take pleasure in accumulating trivia knowledge and imposing order on things. In other words, nerds.

Gygax became obsessed with war games. He co-founded a group, the lofty-sounding International Federation of Wargaming, and in 1968 organized Gen Con, a war gaming convention in Lake Geneva. Three years later, he published his own game, Chainmail, which simulated individual medieval combat. Figurines represented knights and pikemen and archers and so on. Players used dice to resolve the outcomes of attacks. His work as an insurance underwriter had given him a healthy appreciation for the role of probability and random chance in life.

Gygax, who learned pinochle when he was 5, enjoyed both knowing the odds and then rolling the proverbial dice anyway. "I wasn't popular in the home office because I wasn't chicken," he told Wired in 2008. "I'm just a risk taker. I have gut instincts."

Chainmail was a modest success. But its most significant contribution to gaming history was a supplement in the back of the rulebook explaining options to add fantasy elements to the game—wizards, elves, orcs, and of course a big, red dragon. Every creature had unique statistics that determined its defensive and offensive skills.

War gamers at the time were historical purists, and many of them scoffed at such heresies. The fantasy supplement did, however, catch the eye of Dave Arneson, a 21-year-old college student in Minneapolis. Arneson's local gaming group liked the expanded Chainmail system well enough, but there was something missing from the little metal figurines' skirmishes, even when Arneson did silly things like give a druid a Star Trek phaser. The battles had no context, no stake outside of the transient victory of one generic force over another on a given night.

As the story goes, Arneson spent a weekend watching classic Hammer horror films and reading pulp fantasy; the next time the group arrived at his house, he had set up a mock castle dubbed Blackmoor. He told the players that each of them would control an individual hero. Instead of storming the castle, they would explore it together. Castle Blackmoor was abandoned, a ruin.

In his parents' basement, Arneson had stumbled on something that would change gaming and pop culture forever.

'Those Whose Imaginations Know No Bounds'

By marrying the combat mechanics of Chainmail to free-wheeling storytelling, Arneson allowed people to take on the roles of the heroes on the board—to go on a quest. Players became much more than Monopoly thimbles or steel soldiers—instead, they were strong fighters or a wise wizards. Because all creatures were represented numerically, numbers could represent any creature.

And persistent character sheets could be kept, allowing games to be linked together in an ongoing campaign. Experience could be tracked, and veteran characters could gain greater skills and new abilities. Arneson modified the Chainmail rules to give players "hit points" and took on an expanded role as referee, setting the scene and guiding players through scenarios.

Arneson drove down to Lake Geneva to show his half-formed experiment to Gygax, who immediately recognized it for what it was: brilliant. "I think we can make something special out of that," he told Arneson after their first late-night play session.

Arneson's handwritten notes were mostly incomprehensible, but they were enough. The various pieces that would become D&D had finally been joined together, and now the puzzle was solved. Gygax sat down at his typewriter and banged out a first draft of "Fantasy Game" in two weeks. At the time, he was unemployed and making spare cash by cobbling shoes in his basement.

After a year of rewrites and play testing, Dungeons & Dragons was released in 1974 by Tactical Studies Rules (later known as TSR), a company Gygax and two friends formed after other gaming companies passed on D&D. It was co-credited to Gygax and Arneson.

It took eleven months to sell the first 1,000 copies. The next run sold out in six months. After that, TSR started measuring sales by the thousands per month. It spread through hobby shops and by word of mouth, not just among the old-guard grognards who had come up in the historical war-gaming scene but among sci-fi and fantasy fans, too.

The product itself wasn't pretty, and the rules were still a confusing mush, even to regular war gamers. The idea, though—the pure potential of it—was apparent. Players were willing to forgive the flaws for a chance to be someone else in another world.

Arneson, by all accounts more of an ideas man than a nuts-and-bolts designer, was pushed out as the company began cleaning up the rules and releasing the next major versions of the game. Published between 1977 and 1980, the three rulebooks of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, written entirely by Gygax, together formed a giant compendium of every monster, rule, and reference table an aspiring player or dungeon master could ever want (and more).

J.R.R. Tolkien was a major touchstone. Even though Gygax disliked the prim, sexless high fantasy of The Lord of the Rings, he couldn't help but adopt many of its tropes: Elves are graceful, dwarves live in mountain strongholds, orcs pillage, and rangers range o'er the wilderness.

The product itself wasn't pretty, and the rules were still a confusing mush. The idea, though—the pure potential of it—was apparent. Players were willing to forgive the flaws for a chance to be someone else in another world.

But Gygax had spent his formative years reading every piece of pulp fantasy he could get his hands on as well, and for this project he drew on the best the genre had to offer. D&D's magic system was based off Jack Vance's weird, far-future Dying Earth stories. There were also healthy amounts of sword and sorcery (Fritz Leiber and Robert E. Howard), from which the game took its skulking thieves, its mighty-thewed fighters, and its early preoccupation with scantily clad women. Creatures from mythologies and folk tales—medusas, minotaurs, rakshasas, hags, werewolves—made appearances in the Monster Manual. Dinosaurs, Arthurian knights, and Lovecraftian horrors were thrown in for good measure.

It looked, in other words, like what would happen if you opened up a preteen boy's imagination and dumped the contents on the floor.

Exit the Warrior

By the early 1980s, Gygax had retreated to L.A., separated from the mother of his five children, and spent gobs of money pursuing a D&D movie that never materialized. In the meantime, he rented King Vidor's old mansion in the Hollywood hills, power-lunched with big shots during the day, and hosted hot tub parties at night.

Living it up in Hollywood, Gygax was oblivious to the looming catastrophe at TSR. Despite astronomical growth and gangbuster sales, the company was in trouble. The game had reached just about every basement and dorm room it was going to, and its publisher—unusually structured and lacking anyone with major business experience—was hemorrhaging money from frivolous expenses and harebrained side projects, Gygax's among them.

By 1984, the company was $1.5 million in the red and on the verge of being cut off by its bank. Gygax returned to Wisconsin and brought on Lorraine Williams, the heiress of the Buck Rogers fortune, as a business manager to impose fiscal sanity.

The party ended in 1985, when Williams, increasingly at odds with Gygax, bought out the shares of other two board members in a backroom deal, making her the majority shareholder in TSR.

Gary Gygax, the consummate war gamer and strategist, was outmaneuvered and ousted from his own company, which then sued him semi-frequently throughout the '80s and '90s whenever his attempts to publish new work strayed too close to TSR's expansive definition of its intellectual property.

After all the turmoil and drama and millions of dollars, Gygax ended up right back where he'd started, designing fantasy games out of his house. They sold in modest numbers to hobbyists, but never came anywhere close to the zeitgeist-shifting impact of D&D. His last major quest was an attempt to recreate Castle Greyhawk, the 50-level-deep megadungeon from his first D&D campaign—the first D&D campaign. Health problems forced him to shelve the project in 2005. After two volumes spanning several hundred pages, he'd only made it to the upper works of the castle.

The Nerds Take Over

It's a happy coincidence that D&D and the personal computing revolution occurred at roughly the same time. Computer programmers were quick to realize that their new machines could easily replicate D&D's numbers-based mechanics.

The first examples were such late-'70s text-based adventures as Colossal Cave Adventure and Zork: The Underground Empire. Both focused on exploration and puzzle-solving.

Also around that time, a Houston teenager named Richard Garriott was designing one of the first combat-heavy computer role-playing games as a school project. Released in 1980 as Akalabeth, the working title of the game had been "D&D." Garriott followed up with the Ultima series, one of computer gaming's all-time greats.

The plot of Doom, the seminal 1993 first-person shooter, was inspired by ID Software's in-house D&D campaign, after a player destroyed the game world by accidentally opening a portal to hell.

Sales of D&D waned during the late '80s and '90s as video games took over, but its cultural influence only spread. A generation that had grown up playing Dungeons & Dragons was coming into its own, and the game had left an indelible mark on their creative output. One can catch snatches of Gygaxian language and D&D conventions everywhere from the writings of Ta-Nehisi Coates to the Cartoon Network series Adventure Time, along with more overt references in shows such as Community and Stranger Things.

'Game Said to Inspire Mind, Raise Satan'

The radical, unsupervised fun offered by D&D, which by the late '70s was selling more than 6,000 units a month, did not go unnoticed.

Satan, that old deluder, was at work everywhere in America, much as he had been in New England circa 1692. Heavy metal music, violent TV shows, and of course D&D—an inscrutable game full of spells and demons—were all part of his toolbox. The newly energized religious right was just waiting for an incident to confirm its suspicions.

It happened in 1979, when James Dallas Egbert III, a gifted 16-year-old computer science major at Michigan State University, disappeared.

Egbert left a suicide note in his dorm room but no other trace of his whereabouts. With a police search coming up empty, Egbert's parents hired a private detective, William Dear, to find their son.

Egbert was a D&D player, and gamers at the college would sometimes sneak into the steam tunnels underneath the university to play. Dear theorized that the teen's disappearance may have been a case of role playing turned deadly serious. The press ate it up.

Egbert surfaced a month later in Louisiana. It turned out he had gone into the steam tunnels with a goal of overdosing on Quaaludes; when that didn't work, he fled. He was under enormous academic pressure from his parents, socially isolated, and in the closet. He never got over his depression and a year later ended his life.

The Egbert incident, minus its all-too-real denouement, was fictionalized and sensationalized in the 1981 book Mazes & Monsters. The story was then adapted into an even worse made-for-TV movie starring a young Tom Hanks as a role player who loses his grip on reality and almost jumps off a building, believing he can fly.

D&D was linked to a string of teen suicides in the following years, brought on, according to the game's critics, by kids' inability to distinguish the game world from reality.

In 1982, a mom named Patricia Pulling formed the group Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons (BADD) after her son fatally shot himself. She claimed he had committed suicide because of a curse placed on his D&D character.

Pulling then became a source for other morality police enlistees, including Tipper Gore, America's foremost scold, who regurgitated Pulling's claims in her 1987 book, Raising PG Kids in an X-Rated Society. "From THE EXORCIST to the Dungeons and Dragons fantasy role-playing game, Americans chased one occult fad after another," Gore wrote. "The game is based on occultic plots, images, and characters which players 'become' as they play the game. According to Mrs. Pulling…the game has been linked to nearly fifty teenage suicides and homicides."

Excitable Christian groups campaigned to get the game banned from schools and public libraries, where less uptight adults were using it as an extracurricular educational tool. Evangelist Jack Chick, famous for his corny comic-book tracts about the mortal perils of hell, released a strip in 1984 about a young gamer named Debbie who is inducted into a real-life witch coven.

Some of the game's sillier critics credulously repeated claims that D&D books emitted screams when thrown in fireplaces. The media obliged them with both-sides reporting that resulted in coverage like this 1986 Richmond Times-Dispatch headline: "Game Said to Inspire Mind, Raise Satan."

Attempting to stamp out the fire, Gygax appeared on 60 Minutes in 1985. The episode trotted out a list of teens who had allegedly committed suicide because of D&D, mostly based on overheated police reports. It included emotional interviews with Pulling and psychiatrist Thomas Radecki, a founding member of the National Coalition on Television Violence and a frequently cited "authority" on D&D. Radecki said there were scores of suicides and murders directly attributable to the game.

"You're role playing, you're rehearsing, you're developing the character hour after hour, day after day," he said. "We're really talking about intense involvement in a very serious form of violence."

Gygax scoffed: The spells in D&D are as real as the money in Monopoly, he pointed out. But it's hard to win an argument against a crying mother.

After the show aired, Gygax forwarded the producers letters from two mothers of other children cited by 60 Minutes as D&D suicides. They said the game had nothing to do with their kids' deaths. CBS never issued a retraction.

Radecki would later have his medical license suspended, twice, for professional misconduct. He is currently serving an 11-to-22-year prison sentence for overprescribing opioids and trading drugs for sex.

It all sounds ridiculous in retrospect, but it was no laughing matter for TSR, where employees started receiving death threats. Gygax hired a personal bodyguard during the height of the hysteria. While the accusations of devilry and forbidden evil were a P.R. nightmare for the company, however, they didn't hurt sales: In 1982, TSR posted revenues of $16 million. By 1985, the number approached $30 million.

Taking D&D to the Dungeons

Although D&D is no longer considered a gateway to Satanism, there is one place where it has often been dangerous to play it.

The books are banned in some American prison systems. Even where they're allowed, dice are frequently prohibited to discourage gambling, forcing players to create their own contraband d20s or come up with creative alternatives. This state of affairs has led to some of the more unusual civil rights cases in U.S. legal history.

"I've taught murderers, gang bangers, and straight up Neo-Nazis to come together," the former inmate wrote, "and work as a team to slay vampires, save the world, and most importantly, set aside any preconceived notions and attitudes for the common goal of having fun and getting ones head out of a TRUE Dungeon."

In 2004, the Waupun Correctional Institution in Wisconsin decided to ban D&D and confiscated a small mountain of campaign materials from inmate and dungeon master Kevin Singer's cell, including a 96-page handwritten manuscript. Singer, a lifelong D&D enthusiast, sued the prison, arguing the ban violated his First Amendment rights. The case wound its way to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, where a panel of august judges found themselves considering the security threat presented by inmates pretending to be wizards.

The prison's gang specialist testified at the trial that D&D can "foster an inmate's obsession with escaping from the real-life correctional environment, fostering hostility, violence, and escape behavior." That in turn "can compromise not only the inmate's rehabilitation and effects of positive programming but also endanger the public and jeopardize the safety and security of the institution."

The 7th Circuit, ignoring affidavits from other inmates and from advocates of role-playing games, sided with the jailers. "The question is not whether D&D has led to gang behavior in the past; the prison officials concede that it has not," the court wrote. "The question is whether the prison officials are rational in their belief that, if left unchecked, D&D could lead to gang behavior among inmates and undermine prison security in the future."

Until recently, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections banned D&D manuals and similar role-playing games under the category of "writings which advocate violence, insurrection or guerrilla warfare against the government or any of its facilities or which create a danger within the context of the correctional facility."

Pennsylvania now allows the books, but playing the game is still forbidden, a spokesperson for the agency writes. The reason? "It is a hierarchical game. There is concern that such a competition could lead to violence."

The official stigmatization and profound misunderstanding of the game hasn't quelled demand for it behind bars. Michelle Dillon, a project coordinator at Books to Prisoners, a Seattle-based nonprofit that collects and mails reading materials to inmates, says her organization gets one to two requests a week for D&D and similar tabletop games.

"We were surprised by our results, but when we started to think about it, the drive to play [role-playing games] definitely made sense," Dillon writes. "Time stretching in front of the prisoners, access to limited supplies outside of pencils and papers, and a desire to express creativity—what could be better than a game like D&D? And the returns for the inmates have the potential to be immense: skill building in strategic planning, in mathematics and probability, in teamwork, in storytelling, and even benefits for prisons that result in groups having an outlet for stress and boredom."

When I put out a call on the website Reddit for stories about playing D&D in prison, I received this response from one former Texas inmate: "I've taught murderers, gang bangers, and straight up Neo-Nazis to come together and work as a team to slay vampires, save the world, and most importantly, set aside any preconceived notions and attitudes for the common goal of having fun and getting ones head out of a TRUE Dungeon. I believe that games like D&D can be a powerful tool to inspire creativity, to provide a means of escape, and to give the vilified an opportunity to be the 'Good Guy' that the world in which we live rarely does."

The podcast Ear Hustle, recorded and produced by inmates at California's San Quentin State Prison, revealed a real-life example of this in its first season. Inside San Quentin, the unspoken rules of race control all aspects of life. Everything from the showers to the cafeteria is self-segregated. In the prison yard, each race controls strictly defined and inviolable territory. The only integrated space in the whole yard, it turns out, is the small spot where D&D and other games are played.

'Gary Gygax Saved More Lives Than Penicillin'

By 1997, TSR was facing another major cash crunch and teetering on the edge of insolvency. Williams sold the company to Wizards of the Coast, publishers of the popular Magic: The Gathering card game.

The fourth edition of D&D, released in 2008, was not well-received. It tried to adopt the combat mechanics and feel of massively popular online role-playing games such as World of Warcraft. But in doing so, it abandoned much of the looseness and space for creativity that made D&D special in the first place.

For the fifth edition, released in 2014, the designers went back to the drawing board, stripping out many of the most complicated rules and number-crunching requirements while emphasizing core creative gameplay. It has been a massive, unqualified success—satisfying core fans and grizzled grognards, bringing in new players of all ages, and even starting to bridge the infamous gender gap in the game.

Although advertisements for D&D in the '70s and '80s always included an obligatory girl player at the table, there was a chauvinistic attitude within the cloistered fraternity of war gamers that lady brains simply weren't wired to be interested in gold and glory. Internal and external surveys from the late '70s showed that the percentage of female players was in the low single digits; one didn't have to be proficient in the "investigation" skill to figure out why girls weren't rushing to play games that included a "harlot table" and where women in the stories were often little more than furniture on which boys could act out their less chivalrous fantasies.

The new D&D rulebooks no longer include pictures of women in improbably skimpy outfits, and women now account for about a quarter of the game's players.

The mainstream popularity of The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Game of Thrones has made being a fantasy nerd no longer a badge of dishonor, while the internet has given fans a giant trove of homebrew content and entertainment.

D&D diehards can watch professional actors such as Joe Manganiello (True Blood, Magic Mike) play the game on the web series Critical Role, or tune into Wizard of the Coast's Twitch channel, which streams 50 hours a week of live-play D&D sessions, including the all-female group Girls Guts Glory and "Uno Partido Mas," a Spanish broadcast.

All in all, there's never been a better time to be a Dungeons & Dragons player.

As for Gygax, it's hard to square the "eccentric and frightening" figure presented in the FBI's reports with the public image of him in his later, mellowed years: a smiling man with a gray beard and ponytail.

The FBI investigation into cocaine trafficking in Lake Geneva, at least as far as it concerned Gygax, apparently went nowhere. In any case, he was a Young Republican in the 1960s and reportedly smoked some pot in the '70s, all of which probably puts him somewhere below the median drug use of his generation.

He enjoyed hunting as a kid and owned firearms as an adult, but his collection was no larger than that of hundreds of thousands of other Americans.

The alleged Liberian tax haven that the FBI accused him of using appears in no other articles or biographies of Gygax, although Williams, Gygax's former nemesis, says in Of Dice and Men that TSR "had all sorts of offshore operations" when she joined the company.

Gygax spent his last few years enjoying his status as a sage elder—going to conferences and playing games with the many pilgrims, journalists, and longtime friends who showed up on his porch in Lake Geneva.

When Gygax died in 2008, one of his fans, the San Francisco artist Chicken John Rinaldi, eulogized him in an email to Reason: "Gary Gygax saved more lives than penicillin. When I was 10, he was 39. He knew he was writing a book for 10 year olds…but never talked down to us. He was the only adult presence in my life from the time I was 10 to the time I was like 15 that didn't preach, didn't talk down, and didn't have any parameters."

In the end, Gygax didn't write a manual for how to slay dragons and advance to level 20. He gave people a guide for unleashing their imaginations and recapturing the art of telling stories with friends. All he asked, in the even voice of the dungeon master, was that we decide what to do with it next.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "The Radical Freedom of Dungeons & Dragons."

Show Comments (72)