Why Is Socialism So Damned Attractive?

Because evolution wired our brains for it.

What is the attraction of socialism? The Cato Institute held a policy forum Wednesday to consider that question, featuring talks from the moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt and the evolutionary psychologists Leda Cosmides and John Tooby.

One problem they quickly encountered was how to define socialism in the first place. Is it pervasive, state-directed central planning? A Scandinavian-style safety net? Something else? Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who pursued the Democratic presidential nomination while describing himself as a socialist, attracted a big following among voters under age 30. But most of those voters actually rejected the idea of the government running businesses or owning the means of production; they tended to be safety-net redistributionists who want to tax the rich to pay for health care and college education. And this was, in fact, the platform Sanders was running on.

Cosmides suggested the contemporary left/right divide rests on the question of whether people are inherently good or bad. The liberal thinks people are good but are ruined by exploitation; the conservative thinks people are bad and their selfish impulses must be reined in by cultural norms and controls. In fact, she continued, evolutionary psychology shows that human nature is composed of an extensive set of neural programs that are triggered by different experiences. Human beings evolved to handle the social challenges encountered in small bands of 50 to 200 people. Globe-spanning market economies strain our brains.

Cosmides than critiqued the Marxist belief that early hunter-gatherers practiced primitive communism—that all labor was collective, and the products of that labor were distributed on the rule of from each according to his ability to each according to his need. Cosmides cited a classic study by the University of Utah anthropologists Hillard Kaplan and Kim Hill, who looked at how Ache foragers shared food. They reported that rarer, high-yield, hunted foods like game were more extensively shared than more common gathered plant foods. Finding game depends a lot on luck whereas finding plant foods depends more on effort.

Such behavior reemerged in a 2012 experiment conducted by the Nobel-winning economist Vernon Smith, Cosmides noted. The study, which was published in The Proceedings of the Royal Society B, had modern college students hunt and gather in a virtual environment. In one patch, resources were highly valuable but hard to find—in economic lingo, they were high-variance. In another patch, the resources were more common and less valuable: low-variance. Since acquiring high-variance resources depends a lot on luck, sharing emerged quickly among participants who foraged in that patch; they recognized that otherwise they could easily go home with nothing. In low-variance situations, by contrast, how much you earned depended chiefly on how hard you worked. Sharing was almost non-existent among the low-variance foragers.

Cosmides then turned to a fascinating 2014 study in The Journal of Politics by the Danish political scientists Lene Aarøe and Michael Bang Petersen. Aarøe and Petersen found that certain cues could turn supposedly individualistic Americans into purportedly welfare-state loving Danes, and vice versa.

In that experiment, researchers asked 2,000 Danes and Americans to react to three cases involving a person on welfare. In one, they had no background information on the welfare client. In the second, he lost his job due to an injury and was actively looking for new work. In the third, he has never looked for a job at all. The Danes turned out to be slightly more likely than the Americans to assume that the person they knew nothing about was on welfare because of bad luck. But both Americans and Danes were no different in opposing welfare for the lazy guy and strongly favoring it for the unlucky worker. "When we assess people on welfare, we use certain [evolved] psychological mechanisms to spot anyone who might be cheating," Michael Bang Petersen explained in press release about the study. "We ask ourselves whether they are motivated to give something back to me and society. And these mechanisms are more powerful than cultural differences."

Ultimately, Cosmides argued, those of us who want to preserve liberty and prosperity need to understand how human psychology has evolved and understand why evolved attitudes are often counterproductive.

The next panelist, John Tooby, turned to those counterproductive attitudes. Tooby has long been puzzled that so many of his colleagues are not struck by facts like Hong Kong's amazing economic success. (Its GDP increased 180-fold between 1961 and 1996 while per capita GDP increased 87-fold and inequality fell.) Instead, even a Nobel-winning economist like Joseph Stiglitz praised Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez's ultimately disastrous redistributionist economic policies.

The chief problem, he suggested, is that many people are beguiled by "romantic socialism"—that is, they imagine what their personal lives would be like if everyone shared and treated one another like family. We evolved in small bands that were an individual's only protection from starvation, victimization, and inter-group aggression. People feel vulnerable if their band does not exist. Such sentiments are more or less appropriate when people lived in small groups of hunter-gatherers composed mostly of kin, but they fail spectacularly when navigating a world of strangers cooperating in global markets.

Tooby also argued that markets make intellectuals irrelevant. Consequently, academics have a huge bias against spontaneous order and the basic goal of most social science is to critique the social institutions associated with market-based society.

More darkly, Tooby pointed out that political entrepreneurs know how to appeal to romantic socialist sentiments as a way to establish themselves in power. The evolved psychological propensity toward romantic socialism facilitates political coalitions that oppose free-market societies. Since such coalitions are organized around romantically appealing ideas, any heresy is treated as betrayal. If things are not going well (and they never are in full-blown socialist societies) and since the ideology cannot be wrong, evildoers are undermining progress and must be found and punished (think kulaks and the Gulag). Such coalitions tend to revert to primitive zero-sum thinking: If there is something you don't get that means that someone took it from you. The result is, according to Tooby, that there really are those who are willing to make poor people worse off in order to make rich people worse off.

The third speaker was Jonathan Haidt, whose research explores the intuitive ethics that undergird the psychological foundations of morality. His goal is to reconcile the universal human behavior identified by evolutionary psychology with the cultural variations highlighted by anthropology. He and his colleagues have identified six moral foundations, but he focused on just three during the session. Those three were care/harm, fairness/cheating, and liberty/oppression.

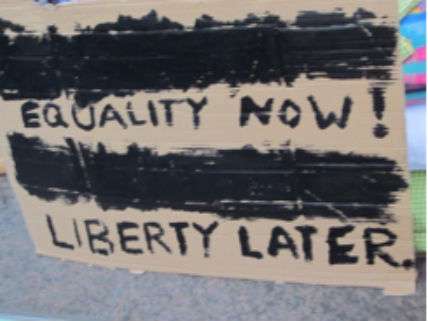

In contemporary politics, liberals are chiefly concerned about care and harm. They see fairness mostly as equality of outcomes. He illustrated this with photos taken during the Occupy Wall Street episode in Zuccotti Park. (One Occupy sign, for instance, read "Tax the Rich Fair and Square.") On the other hand, conservatives see fairness has proportionality; if you work hard, you get to keep the rewards. Haidt showed a Tea Party sign that read, "Stop Punishing Success—Stop Rewarding Failure."

Haidt and his colleagues recognize that the usual two-dimensional political spectrum is inadequate and have studied libertarian morality. Libertarians, they concluded, score lowest on measures of empathy, highest on measures of rationality and cognitive engagement, and off the charts on reactance: the anger you feel when someone tells you that you can't do something or tries to control you.

Haidt is working a book tentatively titled Three Stories About Capitalism. Left-leaning people, he said, endorse a story he calls "Capitalism is Exploitation"; "Capitalism is Liberation" is the story told by many conservatives and most libertarians. Haidt suggested that both stories have some truth to them. One group believes it is standing for decency at the cost of some dynamism; the others favor dynamism while sacrificing some decency. Haidt asked, "Do we need a third story about capitalism?"

Another Occupy Wall Street placard shown in Haidt's presentation said "Equality Now! Liberty Later." In response to that sentiment, Haidt quoted Milton Friedman: "A society that aims for equality before liberty will end up with neither equality nor liberty. And a society that aims first for liberty will not end up with equality, but it will end up with a closer approach to equality than any other kind of system that has ever been developed."

Our evolved psychological programs may more readily succumb to romantic socialism, but as Cosmides, Tooby, and Haidt remind us, there are other brain apps that can turn humanity toward liberty and prosperity. Let's figure out how to activate them more frequently and to use them better.

Show Comments (188)