Learning the Wrong Lessons From the Eminent Domain Legacy at Chavez Ravine

Progressives are trying to fix the errors of the past, but they're ignoring the best solution: More robust property rights.

In their efforts to protect the downtrodden, progressives typically forget perhaps the most important defense the poor and powerless have against discrimination and government abuse: property rights. A nation that protects property rights also protects human rights.

"The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the Crown," 18th century British Prime Minister William Pitt explained. "It may be frail, its roof may shake, the wind may blow through it, the storm may enter, the rain may enter, but the King of England cannot enter; all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement!"

Now imagine that level of freedom, where a private property owner (or leaseholder) can defy kings, presidents, governors, and mayors. That of course explains why most leftists (and some conservatives, too) are fundamentally hostile to strict property protections. Those who want government to achieve grandiose objectives don't want to hamstring officials' ability to achieve their envisioned uplifting.

In 2004, I included that Pitt quotation in my book (

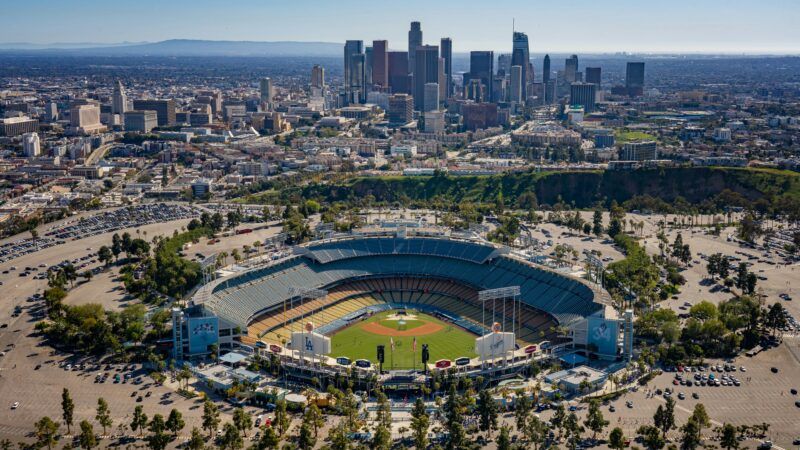

Go figure, but these agencies typically targeted the homes and businesses of the powerless. Yet the state's Democratic leadership and progressive activists were mostly hostile to the movement to rein in the "tool" of eminent domain. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court gave its imprimatur (Kelo v. City of New London) to this troubling process, with the most progressive justices siding with the government's claim of expansive eminent domain rationales. But 20 years later, perhaps progressives are learning their lesson. Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed Assembly Bill 1950, which would have created a task force to study the effects of one of California's best-known examples of eminent domain and also propose compensation. The compensation element of a 1950s-era taking was a reasonable sticking point, but I'm heartened Assembly Bill 1950 received overwhelming support in our Democratic-controlled Legislature. The specific taking is known as Chavez Ravine, which is best known as the spot where the Los Angeles Dodgers have played since the 1960s. It refers to three neighborhoods that were home to 3,800 Mexican-American residents, many of whom were legally restricted from living elsewhere. The city considered the area blighted, but as the bill explains, "these neighborhoods were, in fact, vibrant and cohesive communities, serving as a hub for homeownership and economic development and growth for people of color." One of the city's most outrageous complaints was the area's lack of infrastructure, which wasn't the residents' fault, but the fault of city officials who refused to provide that "shantytown" with the same services provided elsewhere. You can find online myriad stunning and deeply disturbing photographs of Los Angeles officials forcibly removing people from their homes—and bulldozing the nicely kept bungalows. What a travesty. But progressives often gloss over a key point. Unlike redevelopment-era takings that bulldozed neighborhoods to make way for shopping malls and corporate headquarters, Chavez Ravine (referred to by many as "The Poor Man's Shangri-La") was bulldozed to make way for a progressive policy at the time: federal public housing projects. Residents initially were promised new "homes" in the 13 soulless high rises planned for the spot, but the project collapsed after the city's voters—amid concerns about socialist-style housing projects in the thick of the Cold War—qualified a referendum and rejected the project at the ballot. The new mayor opposed the project, which the city ultimately scrapped. It traded the vacant land to the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in a package to bring the team to Los Angeles. A private stadium wasn't a public use, but the city included a large park as part of the project to get around that restraint. Voters narrowly approved the stadium deal. Kelo has unfortunately allowed governments to use eminent domain for anything deemed a "public benefit" rather than the more restrained "public use." This is the second time in recent years that California lawmakers discovered the unjust results of eminent domain. Newsom signed a bill in 2022 to return Bruce's Beach to its owners' descendants. A Black couple owned the Manhattan Beach property in the 1920s and operated a resort that catered to Black families, who had few legal places to swim. For discriminatory reasons, the city used eminent domain to take the property and turn it into a park, although it then sat vacant for years. Progressives have brought needed attention to these examples, although they've focused on their discriminatory aspects. That's fair, but the lack of property rights is the key problem, as every new generation of government planner has its rationale. Instead of passing symbolic bills expressing horror at decades-old outrages, the Legislature should get busy protecting everyone's property rights now. This column was first published in The Orange County Register.

Show Comments (15)