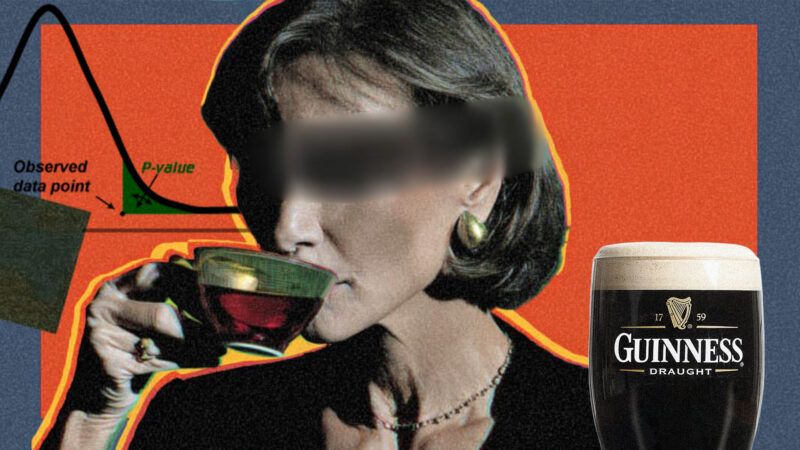

Our Obsession With Statistical Significance Is Ruining Science

A forgotten Guinness brewer's alternative approach could have prevented 100 years of mistakes in medicine, economics, and more.

A century ago, two oddly domestic puzzles helped set the rules for what modern science treats as "real": a Guinness brewer charged with quality control and a British lady insisting she can taste whether milk or tea was poured first.

Those stories sound quaint, but the machinery they inspired now decides which findings get published, promoted, and believed—and which get waved away as "not significant." Instead of recognizing the limitations of statistical significance, fields including economics and medicine ossified around it, with dire consequences for science. In the 21st century, an obsession with statistical significance led to overprescription of both antidepressant drugs and a headache remedy with lethal side effects. There was another path we could have taken.

Sir Ronald Fisher succeeded 100 years ago in making statistical significance central to scientific investigation. Some scientists, along with economists Stephen Ziliak and Deirdre McCloskey have argued for decades that blindly following his approach has led the scientific method down the wrong path. Today, statistical significance has brought many branches of science to a crisis of false-positive findings and bias.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the young science of statistics was blooming. One of the key innovations at this time was small-sample statistics—a toolkit for working with data that contain only a small number of observations. That method was championed by the great data scientist William S. Gosset. His ideas were largely ignored in favor of Fisher's, and our ability to reach accurate and useful conclusions from data was harmed. It's time to revive Gosset's approach to experimentation and estimation.

Fisher's approach, "statistical significance," is a simple method for drawing conclusions from data. Researchers gather data to test a hypothesis. They compute the p-value under the null hypothesis—that's the probability of observing their data if the effect they are testing is absent. They compare that p-value to a cutoff, usually 0.05. If the p-value is below the cutoff—in other words, the data we observe are unlikely under the null hypothesis—then the effect is present.

Fisher pioneered many statistical tools still in use today. But writing in the early 20th century, when science was carried out with fountain pens and slide rules, he could not have anticipated how those tools would be misused in an era of big data and limitless computing power.

Fisher was able to attend Cambridge only by virtue of winning a scholarship in mathematics. In 1919 he was offered a job as a statistician at the Rothamsted Agricultural Experiment Station, the oldest scientific research farm in England. At Rothamsted, then at University College London and Cambridge, Fisher grew into an awesomely productive polymath. He invented p-values, significance testing, maximum likelihood estimation, analysis of variance, and even linkage analysis in genetics. The Simply Statistics blog estimates that if every paper that used a Fisherian tool cited him by 2012 he would have amassed over 6 million citations, making him the most influential scientist ever.

In 1925 Fisher published his first textbook, Statistical Methods for Research Workers, which defined the field of statistics for much of the 20th century. Before its publication, a researcher who wished to draw conclusions from data would make use of a large-sample formula such as the normal distribution. Discovered a hundred years earlier by Carl Friedrich Gauss, the normal distribution is the standard "bell curve" formula for an entire population of observations around a central mean. Fisher's textbook provided tools to analyze more limited samples of data.

How Beer Led to a Breakthrough

The most important small-sample formula in Statistical Methods was discovered by a correspondent of Fisher's, William Sealy Gosset, who studied mathematics and chemistry at Oxford. Instead of staying in academia, Gosset moved to Dublin to work for Guinness.

Guinness was expanding rapidly and shipping its product worldwide. By 1900 it was the largest beer maker in the world, producing over a million gallons of stout porter each year. At such scale, it no longer made sense to test each batch by taste and feel. Guinness set up an experimental lab within its giant brewery in St. James's Gate, Dublin, to systematically improve quality and yield, and staffed it with talented young university graduates. Gosset and his colleagues were among the first industrial data scientists.

Gosset's interest in small-sample statistics flowed from his everyday work. Beer takes three ingredients: yeast, hops, and grain. The grain in Guinness is malted barley. To prepare the barley, you steep it in water, allow it to germinate, and then dry and roast it, which malts the starch into sugar that the yeast can digest. The amount of sugar in a batch of malt affects the taste of the beer, its shelf life, and its alcohol content, and was measured at that time in "degrees saccharine."

Guinness had established that 133 degrees saccharine per barrel was the ideal level, and was willing to tolerate a margin of error of 0.5 degrees on either side. The brewer could take spoonfuls from a barrel of malt, test each spoonful, then take the average. But how accurate would that average be—should he take five spoonfuls or 10? Gosset verified that small-sample estimates are more spread out than a normal distribution, because you might draw a spoonful that is unusually high or unusually low in sugar, and in a small sample such outliers will have outsize influence.

Gosset was unable to mathematically solve the distribution of a small sample. Impressively, he wrote out a formula based solely on his intuition. To check his work, Gosset made use of a set of physical measurements taken by the British police from 3,000 prisoners. He wrote each prisoner's height and finger length on a card, then shuffled the cards and divided them into groups of four. The averages of the four-card samples had a distribution that matched closely with his formula.

That formula was immediately useful in his job of industrial quality control. Guinness now had an exact formula for the number of samples that would yield a desired level of accuracy. Guinness scientists were allowed to publish their work in academic journals on two conditions: The paper must not mention Guinness or any beer-related topics, and it must use a pseudonym. Under the name "Student"—he kept his laboratory notes in a notebook whose cover read "The Student's Science Notebook"—Gosset published his small-sample formula in 1908.

The height of plants and prisoners, the degrees saccharine of a batch of malt, the test scores of college applicants, and many other real-world examples are approximately normally distributed. Thus, knowing the distribution of a small sample drawn from such a population would be useful in many areas of science. Ronald Fisher, then a Cambridge undergraduate, recognized the potential of Student's distribution, and in 1912 he mathematically proved the formula that Gosset had guessed.

Gosset's formula was a product of his work at Guinness. But the formal proof was all Fisher, as was the organization of Statistical Methods for Research Workers. One of the reasons Fisher's textbook was so influential was an innovative feature: It included a set of statistical tables. The researcher could pick the distribution that corresponded to their data and look up the p-value in the corresponding table.

Gosset was unimpressed with this emphasis on p-values. In a 1937 letter, talking about a comparison of crop yields at different farm stations, he wrote that "the important thing in such is to have a low real error, not to have a 'significant' result at a particular station. The latter seems to me to be nearly valueless in itself." Gosset was not interested in statistical significance, and he had no null hypothesis to test. His interest was in accurately measuring the yield. The economists Aaron Edlin and Michael Love call this philosophy "estimation culture."

The Flaws in Fisher

In his 1936 textbook, The Design of Experiments, Fisher formally laid the foundation of significance testing. On page 6, Fisher describes an acquaintance, a British lady who claims that she can distinguish by taste whether the milk or the tea was poured first. Fisher is skeptical. He proposes having the lady drink eight cups of tea, four milk-first and four tea-first, in random order, and try to guess which was which. How, he asks, should we evaluate the data from this experiment?

Fisher advised calculating the probability of observing your data under the null hypothesis that the lady has no tea-tasting ability. If she is picking at random, she might get all eight cups of tea correct by chance, but the probability of that happening is one in 72—a p-value of 0.014. Fisher then proposes that a p-value under 5 percent is "statistically significant," while a p-value greater than 5 percent is not.

The Fisherian approach flows from the specifics of the tea-tasting example. The binary, yes-or-no approach arises because the fundamental question is "Does the lady have tea-tasting ability, or does she not?" We are not trying to estimate how much tea-tasting ability she has. This feature of the tea-tasting experiment—the binary yes-or-no question—is critical to the Fisherian approach. Without it, statistical significance is unhelpful at best, actively misleading at worst.

The original sin of statistical significance is that it sets up an artificial yes-or-no dichotomy in how we learn from data. Fisher himself would agree that his 0.05 threshold for significance is arbitrary. But this arbitrary cutoff leads us to discard useful information. Imagine you run an expensive randomized trial of a new drug and find that it miraculously cures patients of pancreatic cancer—but only in a few rare cases, so that p = 0.06 and the result is statistically insignificant. Hopefully, we would not toss the project. Put differently, experiments do not exist merely to test the null hypothesis. Their purpose is to advance human knowledge, such as finding cancer cures.

Many important scientific experiments are completely outside of the Fisherian statistical significance model. For one sterling example, 16 years before the publication of The Design of Experiments, Robert Millikan and his graduate student, Harvey Fletcher, performed their oil-drop experiment at the University of Chicago. Millikan and Fletcher set up a mechanism that sprayed droplets of oil past an X-ray tube and then between two metal plates wired with an electric current.

As the droplets passed the X-ray tube, they became ionized—that is, they absorbed one or more extra electrons and gained a negative charge. By gently varying the voltage between the metal plates, Millikan and Fletcher could see when the oil drops floated in midair, precisely balancing the electrical force with the pull of gravity. That level of electrical current, plus the weight of the average oil drop, let them estimate the charge of the electron.

The oil-drop experiment was such a tour de force that Millikan received the Nobel Prize in physics just 14 years later, in 1923—two years before the publication of The Design of Experiments. But what null hypothesis were they testing? Nobody thought that the charge of an electron might be zero. Instead, the oil-drop experiment is a towering example of estimation culture: an experiment to measure the world we live in.

How Statistical Significance Causes Publication Bias

Significance culture versus estimation culture might seem like a minor technical debate. If you're not a tenure-track academic, you may find it hard to believe how much one's career depends on getting "significant" publishable results. In my own field of economics, Isaiah Andrews and Maximilian Kasy estimated that a statistically significant result is 30 times more likely to be published than a nonsignificant result. In the prestigious American Economic Review in 1983, the economist Ed Leamer wrote, "This is a sad and decidedly unscientific state of affairs…hardly anyone takes anyone else's data analysis seriously. Like elaborately plumed birds who have long since lost the ability to procreate but not the desire, we preen and strut and display our [p]-values."

We might imagine that medical studies are held to a higher standard. But in a 2008 study in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers gathered data from 74 preregistered studies of antidepressant medications. Of the 38 studies that found a statistically and medically positive result, 37 were ultimately published. Of the 36 that found negative or insignificant results, 33 were either not published or published in a way the researchers considered misleading.

If a doctor relied on the published literature, then, they would see 94 percent of studies yielding a positive outcome. In reality, only 51 percent of studies found a positive outcome—no better than a coin flip.

Individual findings are also distorted by significance culture. Vioxx is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (or NSAID) similar to aspirin. In the year 2000, a clinical trial funded by its producer—the pharmaceutical firm Merck—reported that the difference between the treated and control groups in the rate of cardiac complications "did not reach statistical significance."

But heart issues were quite rare in their patient population. One patient out of 2,772 in the control group had cardiac complications. In the treated group, five patients out of 2,785 had cardiac complications. The risk of the deadly side effect was five times higher among treated patients. But because one and five out of 2,800 are both very low numbers, the p-value of the difference is above 0.05. As a result, it was reported and marketed as having no significant difference.

Less than a year later, Merck pulled Vioxx from the market; follow-up studies had found the NSAID led to an increased risk of heart attack and stroke. In the meantime, millions of prescriptions were handed out.

Statistical significance had a doubly malign effect on the Vioxx study. First, it caused the researchers, editors, and reviewers to ignore the higher rate of cardiac complications because the difference was not statistically significant. Second, and more insidiously, statistical significance meant that they did not think about the relative costs and benefits. We already have aspirin, Tylenol, Advil, and other NSAID drugs, so the contribution to human well-being of Vioxx's ability to alleviate aches and pains was always going to be modest. By contrast, an increase in the risk of cardiac complications is deadly serious. But statistical significance does not consider the importance of the outcome; all that matters is the p-value.

The false-positive problem is getting worse, not better, in the world of big data. As we run more and more studies, we sieve down to smaller and less important effects. At the same time, we increase our sample sizes and run more and more significance tests. As a result, the flood of nonsense findings is rising over time—as predicted in a 2005 PLoS Medicine article by John Ioannidis titled "Why Most Published Research Findings Are False."

Can "Estimation Culture" Improve Practical Science?

Gosset disliked statistical significance. He was interested in estimating useful quantities in the real world, quantifying his confidence around that estimate, and adding up the costs and benefits involved. His 1908 Biometrika paper on the small-sample formula states that "any series of experiments is only of value in so far as it enables us to form a judgment as to the statistical constants of the population." That's estimation culture.

Could we shift the norms and practices of entire fields (social science and medicine, for starters) toward estimation culture? More than 100 years later, we can still look to industry for inspiration. In recent years, there's been a flood of quantitative researchers into software and marketing jobs analyzing the oceans of data collected by companies such as Google and Microsoft.

A 2025 Information Research Studies paper examined over 16,000 statistical tests run by e-commerce data scientists. The researchers found no evidence of p-hacking or selective publication. Unlike academics, data scientists in industry don't need to publish or perish, so they have no incentive to distort their findings; they are paid for accuracy. Just like their forebear at the Guinness brewery, they naturally cleave to estimation culture.

Academics and journalists should do likewise. Start with the estimate itself and our confidence in that estimate. Put the number in context, evaluate its relevance and plausibility, and try to add up the potential costs and benefits on each side. Finally, recognize that the scientific record in many fields presents a severely distorted picture. When reading the academic literature—to say nothing of the media coverage—keep in mind that we see all the positive and significant findings, and far fewer of the negative or insignificant findings.

There is a better way, and it was there in the Guinness brewery with William Gosset 100 years ago. It starts with dethroning statistical significance, moving away from all-or-none frequentist thinking and toward estimation culture.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article draws on the original scholarship of Stephen Ziliak and Deirdre N. McCloskey, whose research into the history of William Sealy Gosset and Ronald A. Fisher has been vital to understanding the history of Fisherian statistics.

Readers interested in both Gosset's and Fisher's legacy and the economic arguments against statistical significance testing can consult their seminal works on the subject:

- Guinnessometrics: The Economic Foundation of "Student's" t Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2008

- The Cult of Statistical Significance: How the Standard Error Costs Us Jobs, Justice, and Lives University of Michigan Press, 2008

- How Large are Your G-Values? Try Gosset's Guinnessometrics When a Little "p" Is Not Enough The American Statistician, 2019

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Ctrl+f "Bayes": 0 results.

D+

Old joke: A Bayesian and a Frequentist are throwing darts in a bar arguing over precision vs. accuracy when a man walks in and proclaims, "I'm the best dart thrower in the world!" The Bayesian and the Frequentist, both skeptical, say, "Prove it." To wit, the man proceeds to blindfold himself, picks up a dart, walks to the other end of the bar, perfectly pirouettes 3X where, upon completion, he's facing completely orthogonal to the dartboard, and hurls the dart. The dart hits the door right as someone is entering, bounces off the door at an upward angle, strikes one of the tin ceiling tiles, bounces off nearest lampshade, skips off the ashtray sitting on the table in front of the dartboard and comes to rest in the bullseye.

The bar erupts in thunderous applause and the Bayesian declares, "Precision vs. accuracy aside... obviously, he is the *best* dart thrower in the world." to which the Frequentist replies, "We can't know for sure unless he does it again."

Im with you. My preference is bayes. Its more informative. And we've even had yo prove they some of the AI correlation that get pushed as truth because AI output it fail when we do further analysis with a Bayesian sampling approach.

LOOOOL 😀 Look at the right wing smooth brain trying to sound like they know something by talking about things that are clearly above his head. Yeah, Bayes is "more informative" and stuff and we've "had yo prove they some of the AI correlation and stuff"... And this one LOLOL "AI output it fail when we do further analysis with a Bayesian sampling approach."

You know whose "output" really "failed" here? LOL 😀 (no, creative smooth brain, it wasn't mine.)

LMFAO, holy shit, this is just one more piece of evidence that right wing dead ends are not gonna make it. So happy. 🙂

I think you posted before making a point.

As usual.

There actually is a point, but right wing smooth brains are unable to extract it. You can assume this with near certainty at this point.

If you don't see how JesseAZov, the russian asset, is talking a mix of pretentious nonsense and stats 101 to sound smart to his tribal comrades, you are just strengthening the hypothesis. Fuck, you guys really are as retarded as they come.

Your first sentence makes it clear YOU are trying to sound like you know a lot about something you have ZERO understanding of. What the person you laughed at knows is irrelevant to that FACT.

My problem with Bayesians is that they tend to be a lot less generous to frequentists than the other way around. Very often Bayesians criticize frequentists for their methods which could produce ridiculous results. But they fail to mention that no reasonable frequentist would ever do such a thing.

The reality is both Bayesian and frequentist models are wrong. IE, "all models are wrong, some are useful." There are tradeoffs between the two schools. The bigger problem in science is people doing statistics with almost no training or study in statistics. "Computer give me answer. Time to publish."

Ctrl+f "Bayes": 0 results.

Just what I was thinking!

I also wonder about expectations/effect sizes. Suppose we have a cohort who all have very high BP - say 180/120. Drug A reduces BP to 175/115 for enough of the cohort for statistical significance. Meanwhile Drug B reduces BP to 120/80 for a small subgroup while leaving the rest unaffected, such that there is no statistical significance. "By inspection" one would prefer B even though A has the desired level of significance. You may even be able to say that on average A only reduces BP by 4 (psi LOL) while on average B lowers it by 20, using an expectations calculation. Yet sticking to the significance approach, A wins.

I did enjoy the article.

That result is likely impossible (if you got enough 120/80 results for it to be anything other than a fluke, it wouldn't be insignificant).

Also, you don't use frequentist statistics to determine the better treatment. You use frequentist statistics to determine if your treatment sample is actually different from your control sample. If it's not different than no treatment, then its not a productive treatment.

(Should probably also be said that nobody competent would only be looking at end p-values. They should have noticed the cluster of unusual results if your hypothetical is even possible, and done more investigation).

WHAT could you have meant with "4 (psi LOL)"?

Neither the number NOR the unit makes any sense to me.

mm Hg?

4?

LOL? It's FUNNY? Call me witless.

This whole thing is related to the modern manufacturing obsession with yields, and yield buzzwords like "5 sigma". Our yields have to be PERFECT!

Well, how many designs and manufacturing processes are forgone because of this? If I invented a process for building an anti-gravity device for an affordable price, but my yield was such that only 1% of devices built, actually work, then would a buyer, or would a buyer SNOT, want to buy the ones that work? ... Silly geese!!! Duh!!!

I think your example works only if a buyer is able to determine whether one worked or not before purchase.

If that’s not possible, then how many buyers would there be for a device that was 99% likely to kill them?

"If that’s not possible, then how many buyers would there be for a device that was 99% likely to kill them?"

None! Granted! What kind of buyer would buy this kind of device without a demonstration or remote-controlled "test drive"?

Along those lines, I never understood the origins of "buying a pig in a poke" or "don't let the cat out of the bag". Look it up if that's not familiar to you... As I understand, people in the middle ages would buy a cat in a bag, sometimes, if they were told that it was a much-more-valuable baby pig, WITHOUT LOOKING IN THE BAG!!! Very trusting people at times, I guess, to the point of foolishness...

"If I invented a process for building an anti-gravity device for an affordable price, but my yield was such that only 1% of devices built, actually work, then would a buyer, or would a buyer SNOT, want to buy the ones that work?"

This is more common than you think. Some manufacturing processes have low yields. Semiconductor manufacturing is a good example of this.

True! They also cherry-pick the ones with the test-verified best performance (higher frequency ratings especially; also "lower latency" or propagation delays) and sell them at a premium, higher price.

Actually, bleeding edge computer chips are made in just this manner.

They are mass produced, and then tested. The ones that work perfectly are sold for the highest price, with a particular model number. On the ones on which some subcomponents don't work, they use a laser or some other tool to disable the non-working subcomponents, and they're sold at a lower price and a different model number, with a smaller set of capabilities [fewer cores, maybe a kind of graphics or floating point arithmetic not in their capabilities, etc.]

-dk

And the only legitimate point in that whole article sits right here...

"Unlike academics (i.e. Gov), data scientists in industry don't need to publish or perish, so they have no incentive to distort their findings; they are paid for accuracy."

WTF would any honest findings require a Gov - 'Gun'?

...because they aren't 'experts' (proven) at-all so they have to DEMAND their status.

The science is settled.

I that intended as sarcasm?

Actual science is based on the premise NOTHING is settled.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2015.18248

Turns out about half of published psychology papers can be reproduced using the same standards described.

Good.

Now do R-squared.

Correlation does not equal causation

It's worse than that with R^2. I've seen talks where someone comes up with a value that is so low as to be laughable and then claim definitive proof of dependence of the entire observed effect on the one variable being diddled.

Sort of shakes one's faith in the reliability of the scientific establishment.

A question from a non-statistician…

My understanding of p-values is that it attempts to determine the likelihood of an outcome happening by chance and thus not representative of the groups as a whole?

Using the Vioxx example, while there were 5x the number of heart problems in the test group versus the control (non-Vioxx) group… my understanding is that the p-value meant that there was no way of knowing whether .17% (5 out of 2,785) of the potentially millions of patients taking the drug would also have a negative outcome.

Put another way, statistically wasn’t it just as likely that only 1 out of every 2,800 people taking the drug would have a problem?

FWIW, I thought Vioxx should have been kept on the market. Even if it produced some multiple of heart issues compared to an alternative, the odds of a single patient developing a heart problem was still a fraction of one percent.

This sounds like a job for the do-calculus.

The main problem is that the "p value" really should be a valuable piece of information, but not the end of the discussion. You also need to be aware of the sorts of data samples that can cause the validity of p-values to break: collinear independent variables, selection bias, missing data, etc. All of those things don't prevent you from studying the data, but you do need to back off on the utility of p-values when you do.

In other words, p-value mathematics needs the study to be designed and run (almost) perfectly for the base mathematical assumptions to fit.

You understand the concept pretty well.

>the odds of a single patient developing a heart problem was still a fraction of one percent.

Which is fine unless you are using the drug in millions of people, and those people have safer alternatives.

"By the time Vioxx is withdrawn from market, an estimated 20 million Americans have taken the drug. Research later published in the medical journal Lancet estimates that 88,000 Americans had heart attacks from taking Vioxx, and 38,000 of them died."

https://www.npr.org/2007/11/10/5470430/timeline-the-rise-and-fall-of-vioxx

If you compare Vioxx to ibuprofen, Vioxx is less safe. But as someone who prescribed and used it, it was so much better a painkiller than ibuprofen its comparison should be with narcotics and it is much safer in terms of addiction and overdose. Its increase in thrombogenic potential could have been mitigated by low dose aspirin. AFAIC the best evidence of how good a drug it was is that when the drug reps were sent around to doctors' offices to collect the samples that they had given out, not a single one was returned (according to the reps I talked to) because the doctors kept them for themselves -- I know I did.

"First, it caused the researchers, editors, and reviewers to ignore the higher rate of cardiac complications because the difference was not statistically significant."

Computing p-values did not cause this, bad experimental design with no accounting for confounders was the culprit.

The author is a knob.

This whole article is one of the poorest written I can remember recently. I am no statistician, not even close. I know the term "p-value" but do not know what it really means, and the article never explains anything about it; what low and high values mean, how it is calculated, nothing.

Then comes "normal distribution". That I do know as the bell curve, but how many other people do? Zero discussion of its significance to the article.

And like you said, that Vioxx failure had nothing to do with statistics and everything to do with throwing out useful results. Some of the others were the same, just shoddy research practices. The remedy is not better statistics. The remedy is reporting ALL results, not just the ones the researcher cherry picks.

The tea drinking lady -- he just says "chance is 1 in 72" without any explanation. Casual readers might like to know where that number came from.

A really shoddy article.

Yeah, this article is an outlier for sure.

I know a bit of cookbook statistics, and, yeah, badly written.

The problem isn't using p values. The problem is setting the threshold too low.

"Sigma" is a measure of how far you are from the center of the distribution. For a normal distribution, 95% of the results will be within 2 sigma.

But that means that if you conduct 20 experiments, you're likely going to have one of them come up with a 'statistically significant' wrong result!

In the physics community, two sigma isn't even considered worth publishing. Three sigma is barely considered to be hinting at something. Their gold standard is FIVE sigma.

Now, for anything dealing with humans, rather than nuclear particles, five sigma is so high as to be absurd. People have too much variation.

But 2 sigma is absurd in the opposite direction. You should probably just ignore any result that's less than three sigma. Using two sigma should get people laughed at in any serious discipline.

Yes, but... it really depends on what your researching and how accessible data even theoretically is. If it's something with human populations, expecting 3-sigma results is probably fine. If it's medical, maybe you should even insist. (Although note that the Vioxx study the author criticizes is for failing to find a difference. Naughty statistics and demanding enough difference that you're confident its different, apparently).

But not all studies are human medical trials, and getting it a little wrong is okay. A 2-sigma result in something like Ecology is just a question asking for more investigation, not the arbiter of truth and final determination of reality. There are plenty of serious disciplines where there are important and interesting questions, but the data is messy and the ability to gather it is hard. Sigma-2 is appropriate in those conditions.

(Meanwhile, having been involved in the struggle to get people to stop looking at raw samples and actually pay attention to the statistics in some applications, getting people to accept a standard more stringent than sigma-2 can be impossible. Even sigma-2 is too strict for what they actually want - permission to take actions based on sample hallucinations.)

Computing p-values did not cause this, bad experimental design with no accounting for confounders was the culprit.

In the larger round; "American Rule", legal proof, public health, and the punitive/anti-capitalism baked therein are the issue.

If the drug saves 9,999 lives but doubles an insignificant risk of the other life, the doubling of an insignificant risk is legally actionable to arguably no end.

This was core to the pro-COVID side. The overwhelming majority of anti-Vaxxers are and were of the mind that the vaccines shouldn't have been paid for up front, shouldn't have been shielded from liability, and that people should've been free to patronize big pharma for any vaccine they wanted. If you felt that being part of 9,999 saved lives was more important than the doubling of your risk of being the other 1, that's your choice.

They and anyone even remotely adjacent to them were (and still are) demonized for such reckless disregard of The Science.

This is it. Whatever valid criticisms one might have of the current state of science, the courts are a sick joke. "Take your chances in court" is seen as a dire warning.

"Imagine you run an expensive randomized trial of a new drug and find that it miraculously cures patients of pancreatic cancer—but only in a few rare cases, so that p = 0.06 and the result is statistically insignificant. Hopefully, we would not toss the project. "

I've attended many prestations form start up pharma companies. There is no "hopeful" about it and the fact this is said indicates the author doesn't know this.

Pharma researchers do a trial, and when the trial is not sufficiently significant, they mine the data for and try again for more limited scope. Hone down the scope of the proposed malidy to be treated of refine the target population. Then do new trials.

Learning is an iterative process of testing, refining and retesting.

And lets not forget that statistics applied to agriculture brought us the green revolution.

Fisher was one of the pioneers in agricultural research!

Reason could do an article on Judea Pearl's methods for analyzing causal effects. Much of this is absorbed by pharma and genetics problems but the approach ought to be productive for identifying the often-obfuscated causes of banking panics, financial crashes and even wars.

I would love to see more articles that require a basic education on reason, so that the right wing residue in the comments section would get a chance to show us how much ponypower their cranial engines really have.

Having Dr. Pearl write such an article would be wonderful!

Just declare statistical correlation to be racist - problem solved.

Worked for Public Choice Theory.

The author seems to have no more than a pop culture understanding of data analysis. Finding cause and effect relations for very small probability events is very hard, and statistics tells us the probability of the effect being real. It is not about politics, or cost-benefit analysis. If an experiment shows the probability of a given effect is no more than chance, then that is "statistically insignificant".

For example say I am trying to see if my coin is a bit bias. If I do 1000 flips and find it 499 heads to 501 tails. That is "statistically insignificant".

The author is an economist, and is unhindered by such concepts as a randomized controlled trial.

The first randomized clinical trial in humans was not done until the 1940s. (Streptomycin for tuberculosis.) But every concern about prospective observational studies applies to randomized clinical trials, and there are additional ethical issues.

What's the p-value on Reason needing to update its art style from the faux punk-aesthetic it's been trying to evoke lo these many years?

How long will they keep KMW on as EIC?

Our Obsession With Statistical Significance Is Ruining Science

Who is "our"?

All the personal p-value analysis I've done is followed by flushing the outcome down the toilet.

This is a very important topic. The process of estimation is so deeply embedded in all life that to underestimate its value is to write off eons of evolution. I appreciate this article. It keeps open the conversation about the value and limitations of statistical analysis where it counts, in its many applications.

I taught my students both ways of analyzing observation data. However, not being majors in the subject area, it probably went over most of their heads.

Lord save us from economists writing about clinical trials.

Hint: The primary endpoint of a clinical trial is to answer the binary question, "does the drug work"? It is NOT to estimate the effect of the drug. That's a separate analysis that is of no consequence if the drug is not first proven to "work."

The effect of the drug tells you whether it works or not.

We now have antibody treatments for Alzheimer's disease that have been approved because they "work" -- the p value for the comparison was lesd than 0.05. But the effects of the drugs are really small.

The primary endpoint of a clinical trial is to answer the binary question, "does the drug work"?

As indicated above, and akin to the failings of the article, this is false. There's usually a decent idea that the drug will work before any clinical trials begin. The clinical trials are specifically to suss out whether it works well enough. It is fair to say that specific or any dose-dependent response is generally secondary.

Ultimately, this is two sides of a fundamental signal v. noise information axiom. The question is never "Does the drug work?" cyanide and water are both effective drugs. The question is "Does the drug do enough of what we want it to relative to what/anything we don't want it to do?"

I used to teach statistics and I used the tale of Gosset, aka "Student," in my lectures about development of the t-test. I'm going to disagree with the author about the utility of p-values. To be sure, the 0.05 Type I error criteria is pretty arbitrary, but any statistician worth her salt will derive alpha/beta risks based on the costs and benefits of making Type I/II errors.

Furthermore, best practice is to publish the p-value and then let the reader decide for himself whether or not to get excited about experimental results.

To be blunt, the article tells a nice story, but the p-value issue raised by it has been well-understood for over a century. Only hacks in the social sciences and economics still do things the way described by the author.

"the article tells a nice story, but the p-value issue raised by it has been well-understood for over a century. "

True.

"Only hacks in the social sciences and economics still do things the way described by the author"

Not true. P values unfortunately remain the gold standard for getting published.

Only hacks in the social sciences and economics still do things the way described by the author.

To be clear, a not-insignificant fraction, potentially half or more of all medical science can't be reproduced.

Many people in all kinds of "hard science" fields in and around medicine consider meta-analyses to be a "gold standard" or "foregone conclusion" leaping off point and it's got p-value issues baked in and multiplied together.

Everyone who has ever studied statistics knows that a p = 0.05 result is not worth anything if causation (rather than correlation) cannot be substantiated by other methods and other ways of looking at the problem.

Statistics is a useful science that can be misused. It's a hell of a lot better to have a lot of statistically significant studies from varied sources than studies cherry-picked to show only the conclusions you approve of.

In the case of pharmaceuticals, having university studies supported by the FDA or NIH only (and not just big Pharma) could take some of the prejudice out of the results or at least lead to more 'negative' published results. Leaving all research to private industry can lead more results that only benefit the sponsoring industry. Drugs are not like potato chips. The customer can't choose if they are dying.

Zero universities have the ability to develop pharmaceuticals. None. And the trend is to defund them so that they have even less capability than today. That is the point of MAHA.

"Zero universities have the ability to develop pharmaceuticals."

That is objectively false.

It's a hell of a lot better to have a lot of statistically significant studies from varied sources than studies cherry-picked to show only the conclusions you approve of.

Varied sources *and methods*. Otherwise, this is a meta-frequentist issue that's little different from p-hunting, confirmation bias, Simpson's Paradox, etc.

Sports medicine is rife with this and has been for decades. A dozen studies from different sources, all with arbitrarily-stringent p-values, use the same method and come to the same "There is an effect." conclusion, but when someone uses a different method or tries to put the method into practice, the effect vanishes... because they were studying the effects of their methodology rather than a/the effect itself.

Best article ever in Reason.

I have a PhD in Biostatistics. I and most of my colleagues have been saying this for decades.

...

I don't know if the author doesn't know what he's talking about or not, but he writes like he doesn't know what he's talking about.

The Millikan example: Physics still prefers to directly calculate error where possible. I learned no Fisherian statistics in Physics - we propagated measurement errors to find the statistical error of our computations in physics lab. Which is what Millikan would have done in that experiment, and which is what any physicist repeating it today would do in that experiment. This is not a null hypothesis test, and we still train people how to do error propagation.

The Vioxx example: Heath makes the classic epistemological error - he assumes that the sample data is the real distribution, which is exactly the problem that frequentist statistics is trying to prevent. I'm going to assume his characterization of the results is correct (although medical studies are some of the worst users of statistics, so I wouldn't be surprised if there was an error in how statistics were applied). You can't just know that 1 in x is different than 5 in x. Samples are estimations of the population distribution, not the actual population distribution. The difference could be due purely to chance, and statistics is how you estimate whether it is or not. Any Mathematician will tell you a perfectly fair coin will only rarely flip the exact same number of heads and tails.

I say this is an epistemological error, because it's a class error of deciding what real knowledge is. That's the problem statistics solves.

(If I had to guess, there are likely two errors in the Vioxx trial with regard to heart risk. The first is a power problem - the statistical test probably did not have enough power to determine whether there was an increase in risk of cardiac complications. As power is a function of sample size, the later recall was because the approval led to enough use that the sample size was much larger, and the trend could be determined -- by the frequentist statistics Heath is deriding!

The second error is a failure to properly account for and appreciate the effect of conducting multiple statistical tests, which would have further reduced the power of the test. After all, they wouldn't have just tested for cardiac risk, they would have tested for a variety of things. Each additional test increases the odds that *some* test would return a false result. A p-value cut-off of 0.05 implies a 1 in 20 chance that the test is true when the reality is false (and similarly a chance of returning false when the reality is true). If you do 20 such tests, the odds that all of them would only be true if reality were true is 1-(1 - 1/20)^20 = ~65%. And the *expected false positives* would be 1. (And conversely, the odds of at least one false negative would also be higher). Many scientists forget to correct for doing multiple comparisons, and the medical (and psychological) fields are especially bad about it.)

Now, if you want to make an argument specifically for Bayes vs. Frequentist... do that (I'm not sure you can demonstrate a difference in the Vioxx example, though, and neither applies to the Millikan experiment). But Frequentist statistics are not wrong, and are incredibly useful.

Many scientific questions are of the form 'is there a difference between two groups?' Gosset's approach would not have answered the medical question in the Vioxx study. (And Heath makes no attempt to demonstrate it would).

Now, there's a problem with scientific *publication*, which creates a severe problem for meta-analysis. (Negative results not getting published and therefore discouraged). But that isn't a problem with the methods of statistics. That's a problem with the norms of publication and university tenure evaluation. Framing this as a problem with statistics is misunderstanding the issue. Heath's framing makes him impossible to take seriously, because he's manifestly incompetent to have an opinion.

I should probably add: this sentence is very problematic: "Imagine you run an expensive randomized trial of a new drug and find that it miraculously cures patients of pancreatic cancer—but only in a few rare cases, so that p = 0.06 and the result is statistically insignificant."

How do you know *it* cures patients of pancreatic cancer? Even the statistics couldn't tell you that (it could at best tell you taking the drug was associated with having your pancreatic cancer being cured).

Heath is putting the epistemological cart before the horse.

The discussion here completely avoids the real current issue about statistical inference. I have fifty years' experience, and many publications in maximum likelihood estimation and statistical inference, and the real issue for me is what is happening in LLM and ML, or what is popularly being called AI. For my work, I want a covariance matrix of the parameters to have a large condition number (which tells you the significant figures in your estimates), a nonzero determinant, and as many degrees of freedom as you can get.

But that's all gone by the wayside. I sneered at neural nets because with zero degrees of freedom, that was turning the data into another set of data. But no one cares about the zero degrees of freedom anymore. LLM and ML are "estimating" models with zero determinants. All my work on statistical inference in structural models is obsolete.