Visit Your Ancestral Homeland

The best sort of travel is that which confounds our expectations rather than confirms our prejudices.

This is part of Reason's 2025 summer travel issue. Click here to read the rest of the issue.

Last year I honeymooned in Rome, which was a long day trip from the tiny 2,500-year-old village in the Campania region of Italy that my maternal grandparents left in the 1910s. Of course I had to go—it was surely my only chance to see where that side of my family had come from.

It's a very American thing to travel to ancestral hometowns, especially if your ancestors were fleeing poverty or political repression. Perhaps more than ever, as America grows less sure of its exceptionalism, we want to be reminded that we are lucky to have grown up in the glittering New World rather than the tarnished old one.

But the best sort of travel is that which confounds our expectations rather than confirms our prejudices. And that's what I experienced on a drizzly day in Fragneto Monforte, population 1,700, known for a relic of the 3rd century martyr Saint Faustina, for an ancient and revered tiglio tree in the town square, and, go figure, for a hot air balloon festival that started sometime around the turn of this century.

I had heard only fleeting references to this speck of a town throughout my childhood, and the stories always drove home how backward, stultifying, and impoverished the place was, even for notoriously poor southern Italy. My mother and her siblings rehearsed a particular narrative about why their parents had emigrated; it was persuasive if uncheckable even before my grandparents died in the 1980s. (They didn't speak English; I didn't speak Italian.) The story went like this: There was no future in Italy back then, especially for peasants like my ancestors. Everyone who could leave, did.

Incredibly, my wife had tracked down a relative of mine via Facebook groups and Google Translate. Part of me worried that we were being scammed—I've seen the second season of White Lotus, where Italian-Americans seeking to connect to their roots in the old country are suckered on multiple levels. We took a surprisingly efficient and well-appointed high-speed train from Rome to nearby Benevento (post-Mussolini, it seems, the trains still run on time) and then a cab to Fragneto Monforte, where Pasqualino, my previously unknown second cousin, met us. He was a tall, strapping 50-something construction engineer. He met us with his wife and daughter, who was training in Rome to become a doctor. With his daughter translating, he explained that he was the grandson of my grandmother's sister and his own mother was still alive at 93.

They gave us the grand tour, which took less than an hour, showing us the houses where my grandfather and grandmother had grown up. I searched for my grandfather's initials in the bricks surrounding the tiglio tree. (Family lore had it that he'd scratched them in before he left for America as a teenager.)

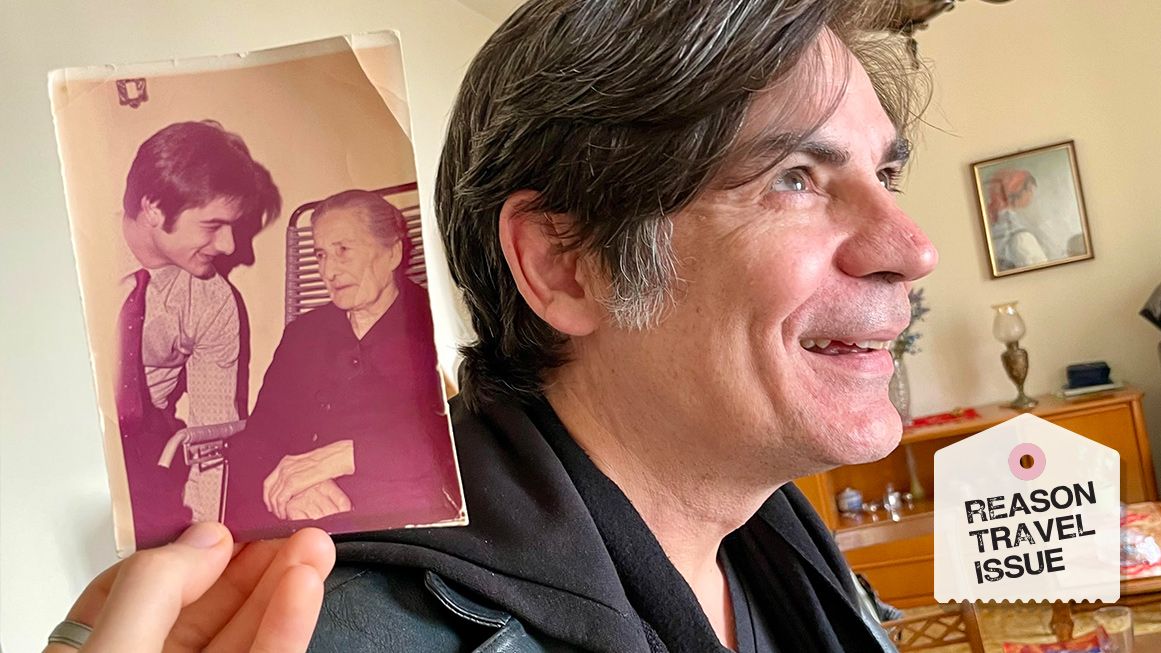

I was eager to meet Pasqualino's mother Anna, a cousin my mother had never known or spoken of before dying in 1999. She was spry for a nonagenarian—and though she spoke no English, her gestures, expressions, and sounds instantly reminded me of my mother and grandmother. She lived in a beautiful house that had been in the family for generations; truth be told, it was far nicer than the house I grew up in, or those of my Italian-American relatives, which occasionally veered into plastic-covered couches, mirrored walls, and gold-foil wallpaper. She brought us drinks and snacks and showed me photos from the '70s, when my grandparents had visited.

I told her I was taught that my grandparents (her uncle and aunt) had left for economic reasons and to avoid war. No, said Anna, they were all doing pretty well, even during World War I and World War II and the rebuilding afterward. They and one other were the only family members who left, she said, and it was never clear why.

Did she ever wish her parents had gone to America? No, she answered: This was always a good place to live.

As I hugged this ancient woman with whom I share a real but tenuous connection and whom I will never see again, I felt for a second like I was hugging my own mother one last time. I was also saying goodbye to family stories that may or may not have ever been true.

Show Comments (99)