'The Tension Between Tradition and Individualism'

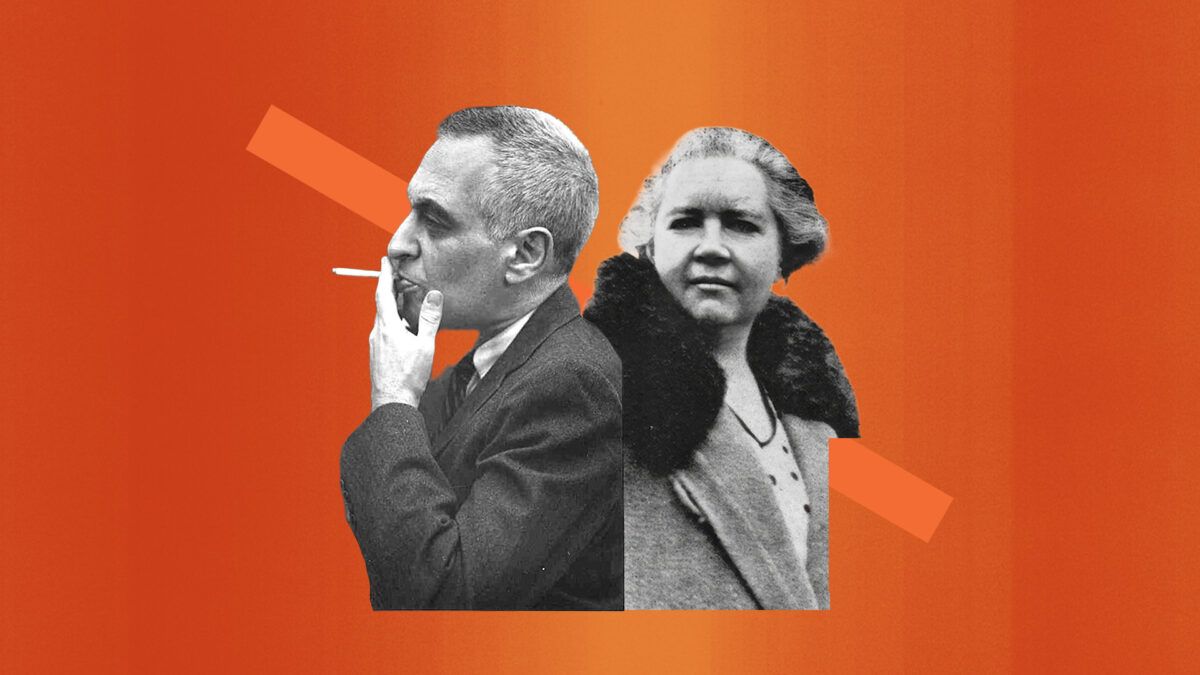

Conservative founding father Frank Meyer and libertarian founding mother Rose Wilder Lane had rich, friendly debates on how much American liberty relied on old European traditions.

Rose Wilder Lane, one of the founding mothers of modern libertarianism, and Frank Meyer, one of the founding fathers of modern conservatism, spent a decade engaged in friendly debate. They both did some work for the Volker Fund, a major source of funding for libertarian scholarship in the 1950s; Volker officer Richard Cornuelle brought Lane to the Meyer home once while passing through Woodstock, New York. The relationship grew from there, with Lane and Meyer trading detailed letters and occasional phone calls from 1953 to 1962.

Their 60 or so letters resurfaced when a trove of tens of thousands of documents saved by Meyer turned up in an Altoona, Pennsylvania, warehouse in 2022. Those papers were a large part of the source material for my book The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer.

Lane's papers, housed at the University of Iowa, in great measure duplicate her live-ink letters found in Meyer's papers, whose cache of long-lost letters includes correspondence with Joan Didion, James Michener, William F. Buckley Jr., and J.R.R. Tolkien.

In a collection overflowing with great writers, Lane shone as the best letter-writer. The Meyer collection's most intellectually captivating and philosophical letters, which include multipage postscripts that strangely leave the reader wanting more rather than less, emanated from her typewriter in Danbury, Connecticut.

Lane confessed a case of poison ivy, noted drifts from the snowstorm that accompanied President John F. Kennedy's inauguration obscuring her windows, and passed along news that an ad in the radio show Queen for a Day suggested that Anbesol would work for Meyer's teething baby son. But even their scant superficial small talk often belied deeper concerns, as when Lane discussed articles on her needlework passion: "I have at last found a legal way of writing for publication without being forced into that Ponzi fraud called, in this country, 'Social Security.'"

Lane became for Meyer something he had lacked during his earlier years, when he had been on the left: a mentor. This aspect of their relationship wasn't really understood by Meyer devotees or scholars until these letters came to light.

When the correspondence began, Lane and Meyer traveled in opposing life trajectories. All but one of the older and established woman's books had already been published. Her mother's Little House series had ended a decade earlier. Meyer signaled his shift rightward by testifying against his former comrades in a 1949 Smith Act trial that sent Gus Hall, Eugene Dennis, and nine other Communist leaders to federal prison. He encountered Lane before his philosophy of "fusionism" gained currency, before the publication of his signature book In Defense of Freedom in 1962, and even before the launch in 1955 of National Review, the conservative publication for which he served as literary editor and unofficial ideologist through his "Principles and Heresies" column.

He benefited from her wisdom and experience. She saw in him a vessel that could carry some of her ideas to new audiences.

The pair hit it off: Both were homebodies, pet lovers, dwellers in old farmhouses, celebrants of liberty but not driver's licenses, and exiles from the left. Whereas Meyer served the open Communist Party at high levels in England and the United States during the 1930s and '40s, Lane inhabited the social circles of Max and Crystal Eastman, Floyd Dell, Jack Reed, and others associated with the freewheeling and more anti-authoritarian Greenwich Village left that collapsed soon after the Russian Revolution. Another common denominator was Austrian economics, which in the form of Friedrich Hayek's Road to Serfdom helped wrest Meyer from Communism.

"I believe Human Action is as important as Galileo's telescope," Lane wrote Meyer of the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises' magnum opus, "or should I say, the books by Copernicus and Galileo."

When Meyer offered an assessment to the Volker Fund of Russell Kirk's proposed monthly periodical that proved too generous for Lane's liking, she let him know. "I think that this whole [Peter] Viereck-Kirk-et al 'conservative' movement," she offered, "is totally pernicious, potentially most dangerous." (Lane, roughly, saw Kirk in particular as being rooted too much in tradition and not enough in an individualistic defense of liberty.)

The following year, when Meyer, with Frank Chodorov's encouragement and Buckley's knowledge, wrote a hit piece of sorts in The Freeman on Kirk's ideas and that generation's iteration of the "new conservatives," a jubilant Lane lamented only that she did not get to see the look on Kirk's face when he read the article. Lane, like many holdovers from the days before the New Deal and World War II, regarded the emergent postwar right with a degree of suspicion. The main challenge to the likes of both Lane and Meyer, though, was a progressivism so dominant that it became the default, obligatory outlook for elites by something like osmosis.

Lane confessed to Meyer that by 1920, when she traveled abroad for the better part of the next decade, "I had never met an American idea. I hadn't an inkling that one existed. I'm sure that none of my friends had. It wasn't that we considered individualism and preferred collectivism; we knew nothing BUT collectivism."

Lane's red-white-and-blue individualism, like Meyer's fusionism, saw freedom as so essential to America's heritage that America and freedom became almost synonymous. Kirk's Anglophilia clashed with their philosophies (though Meyer's love for his six years in England forever shaped him). America played the starring role in Lane's individualism and Meyer's fusionism.

But the most interesting part of the correspondence is where they disagree. Yes, they both celebrated freedom. But they disagreed on its origins. In a word, tradition divided the pair.

Meyer described Americans as the inheritors of a Western tradition that incubated freedom; he felt that America amounted to the sum of all that history. For Lane, America started something entirely new. Lane regarded Europe as collectivist and the Atlantic Ocean a godsend that separated America not from the rest of the West but what she called the "East"—Europe and the Old World. The West was the Western Hemisphere, where the settler mentality saw socialism as starvation and understood that freedom rightly rewarded work. She held that the chasm between New World and Old, not any continuity, propelled freedom in America.

This conflict set off subsidiary debates about revolution, semantics, and if (and when) America had ceased being America.

"I still rather like the word, conservative, and for this reason: respect and support for individualism seems to me to rest philosophically upon the attitude toward the person of ancient Hellas and Israel, of Roman law, of Catholic Christianity," Meyer wrote in October 1953. "The decay of this tradition cuts the ground from under individualism. The tension between tradition and individualism seems to me the essence of the ideal America, which is in turn the consummation of the West."

"Precisely what IS this 'Western tradition' for which you have 'the conservative feeling'?" Lane asked in early 1954. Lane called herself neither a liberal nor a libertarian but an individualist. Meyer regarded all three words as obstacles to conveying to a general audience where he fell on the political spectrum. "Conservative," though not ideal, worked for him.

"Our true banner, Revolution, 'to which the wise and honest [can] repair,' was snatched away as soon as raised; our true name, liberal, was sneak-thieved from us; now even those who know not what they are but blindly want not to be our enemies are robbed of their word, conservative," Lane, relying on a George Washington quote, countered.

Lovers of freedom, Meyer believed, needed to conserve the civilization that bequeathed it. He advanced arguments that would become familiar to readers of In Defense of Freedom. "The West was the first civilization…to give a charter to the individual," Meyer argued. "Freedom is not for Western man 'freedom to do the right,' but freedom to choose right or wrong—the only kind of freedom that has meaning in individual terms."

"So I really do object to your 'Western man,'" Lane responded. "He seems to me a concept that I cannot connect with any actual reality. Who is he? Churchill, Eden, Bismarck, Metternich, Cavour, Clemenceau seem to me to resemble Sun Yat Sen much more than they resemble Adams, Madison, Cleveland, or even Lincoln, that reactionary. Though, push me to the wall and I'll admit a resemblance between them and the two Roosevelts, Taft, Truman and Eisenhower."

Humanity's natural impulse, Lane believed, is not toward freedom; human beings tend to crave organizing other humans. Free men must rebel, and not preserve, the established order.

"A person who acts to defend individual persons, their innate, inalienable liberty, cannot 'conserve' the status quo; he must change it, he must abolish much of it," she informed her pen pal in 1956. "He is an abolitionist, a radical, a revolutionist. That is what he IS, and he can't change the fact by saying he isn't."

'Homesick for Another Good Long Night of Argument'

More than one year into the correspondence, on October 9, 1954, the Meyers did something terribly unusual. They traveled to another person's home instead of hosting. Lane lived in a house that was only 23 feet long and 24 feet wide, and she told the Meyers that a paucity of bedrooms complicated but did not preclude an overnight visit. Her dogs, she promised, would teach their youngest son to climb stairs. Her pride in her home radiated through her 1960 Woman's Day article "Come Into My Kitchen." She wanted the Meyers there.

Lane rested her head in the Housatonic Valley in Connecticut. She held precious memories of her times in the prairie of South Dakota and the hills of Missouri. That earlier life may have at times lacked indoor plumbing, electricity, adequate food, warmth in the winter, and civilization, but there was freedom. Lane needed that as others needed air.

"Your letter makes me homesick for another good long night of argument," Meyer wrote Lane in March 1958. "When are you coming to see us? You have been promising for five years now, and with Spring coming on, I fervently hope you will find the ways and means."

She never did. Their exchange of substantive letters essentially ceased the month of In Defense of Freedom's release. In mission-accomplished fashion, she responded to the book's publication by invoking their exchanges about Kirk nearly a decade earlier. She called it "a joy to me to see your criticism of the neo-Conservatives in print—achievement of a purpose we spoke of, how long ago?"

Lane had fulfilled her role: Meyer no longer needed guidance. Good mentors build in obsolescence. They also act as role models for protégés to emulate. Meyer later secured a job, a grant, and Evelyn Waugh as a reviewer for Garry Wills; lending privileges at the Boston Atheneum for David Brudnoy; and academic positions for scores of right-leaning Ph.D.s through his proto-message board The Exchange. He was a beneficiary rather than a benefactor with Lane. Possibly her kindness inspired him to pay it forward.

Lane recommended him to Ken Templeton at the Volker Fund, which bankrolled Meyer's projects well into the five figures and placed him alongside Murray Rothbard as the foundation's two in-house reviewers of books and scholarly articles. She offered wise advice to personalize stories in his 1961 book, The Moulding of Communists, which he unwisely did not heed. The often exuberant woman boosted his ego by comparing him to Albert Jay Nock and Frank Chodorov, and likened his writing to "an oasis in the contemporary Sahara." When The American Mercury in 1953 fired Meyer as its book review editor, Lane canceled her subscription.

Lane's primary legacy to Meyer involved shaping his outlook. This started just eight years after Meyer exited the Communist Party and just over three years after he clearly identified as a conservative. Whether he knew it or not, he needed a more experienced guide.

One finds her fingerprints all over Meyer's 1965 National Review debate with Harry Jaffa over Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, in which Meyer defended secession and depicted Lincoln as a trampler of the Constitution. They are all over the last major speech Meyer delivered, at the fall 1971 Philadelphia Society meeting, in which Meyer described the postwar conservative movement as a reaction to the New Deal. The pro-freedom position he defended in ongoing debates with Kirk, L. Brent Bozell, and Donald Atwell Zoll surely owed some debt to Lane as well. But she more influenced what Meyer did not believe by forcing him to defend what she challenged. She sharpened his arguments.

One could not out-liberty Lane. Meyer, drawn to extremes as a Stalinist and later as an anti-Communist, followed Lane only so far. In Defense of Freedom listed the preservation of order, the adjudication of disputes, and defense against foreign enemies as the three legitimate functions of government. Lane's final substantive letters to Meyer, days after the book's publication, wondered whether, in principle, even such limited delegations of authority to the state gave up too much. She expressed "serious doubt as to whether Jefferson's necessary evil is in fact necessary." She wondered whether an unarmed populace can ever truly limit a body that holds "an exclusive monopoly of the use of physical force." She noted: "Historically, all states have made war, almost constantly upon the 'subjects' of other states, and sooner or later upon their own 'subjects' or citizens."

After the epistolary boot camp, Meyer understood himself not as a libertarian but libertarianish—a libertarian-leaning conservative. Lane insisted that American freedom, diminished by European influences, owed little or nothing to traditions bequeathed from the Old World. (The Magna Carta? "Over-rated.") Meyer regarded Western Civilization as crucial to the cultivation of freedom. For Lane, freedom happens. For Meyer, freedom develops. This was their difference. They disagreed on tradition. And, as arguers extraordinaire, this was what dominated their correspondence.

"You see, while I still stand, and I think I will continue to stand, straddled between the conservative feeling for Western tradition and the individualist assertion of freedom and hatred of centralized power, in my letters to you I have been defending the conservative pole of my position," he explained in 1954. "How strongly I affirm the individualist aspect I had not realized until I had to put some ideas on paper on a number of questions recently. Of course, it is also possible that your letters have had something to do with this."

This article originally appeared online and was published in print under the headline "'The Tension Between Tradition and Individualism'." The web version has been updated to reflect the print edition.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

I have at last found a legal way of writing for publication without being forced into that Ponzi fraud called, in this country, 'Social Security.’

Exactly. Social Security is a Ponzi scheme and should be left to die.

Traditions can be attractive and comforting for many people. But the essence of liberty demands that following them not be required by law.

This is the kind of article about people and ideas one loves to read. Many thanks to the author.

Good article. Bravo.