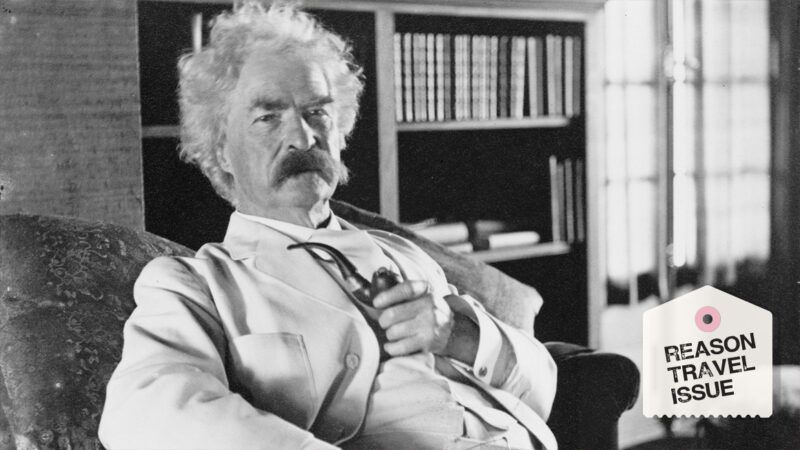

Mark Twain's Travel Log From the Holy Land

Christianity would be wonderful, Twain suggests in The Innocents Abroad, if it weren't for Christians.

The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims' Progress, by Mark Twain, public domain, $5–$40

At just 31, Mark Twain sailed to Europe and the Holy Land on the steamship Quaker City, an excursion that resulted in his first great literary success, The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims' Progress. Published in 1869, it remains one of the world's great travel narratives.

In Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Twain was shown the tomb of Adam. "How touching it was, here in a land of strangers, far away from home, and friends, and all who care for me, thus to discover the grave of a blood relative," he wrote of the site. "True, a distant [relation], but still a relation." This recognition of kinship stirred Twain "to its profoundest depths." Overcome by emotion, he "leaned upon a pillar and burst into tears." We don't ordinarily think of Mark Twain as a champion of Reagan-era "family values," but in his way, he was.

As touching as this might be, it was not quite accurate for Twain to have said he was in a "land of strangers." By the time he and his fellow travelers got to Jerusalem, he had been in their company for more than four months and knew them about as well as he cared to. His experience of traveling with these other Americans was not altogether favorable. There's reason to suspect, in fact, their time together informed the anti-imperialism with which Twain would in later years be associated.

The group's itinerary took them to Spain, France, Italy, and Greece before they arrived in Palestine, where what they knew as the Holy Land was located. Twain was not overly impressed with the natives of any of the countries the Quaker City pilgrims visited. "The people of those foreign countries are very, very ignorant," he reported. Even the French were ignorant: "In Paris they just simply opened their eyes and stared when we spoke to them in French! We never did succeed in making those idiots understand their own language."

At least the French lived in real cities, which could not be said for the Palestinians. The Quaker City vacationers saw much of what we know as Israel, then part of the Ottoman Empire, by horseback. Unlike the more pious travel writers of his day, Twain refused to paint Palestine or its people in glowing terms. It was a "hopeless, dreary, heart-broken land," void of resources, and wherever he and the other tourists went, they found themselves mobbed by "the usual assemblage of squalid humanity" clamoring for money. Some of the men seemed fit, "but all the women looked worn and sad, and distressed with hunger." The little children were "in a pitiable condition—they all had sore eyes, and were otherwise afflicted in various ways."

Twain made no distinctions among people. Jerusalem "is composed of Moslems, Jews, Greeks, Latins, Armenians, Syrians, Copts, Abyssinians, Greek Catholics, and a handful of Protestants," and "the languages spoken by them are altogether too numerous to mention….All the races and colors and tongues of the earth must be represented among the fourteen thousand souls that dwell in Jerusalem. Rags, wretchedness, poverty, and dirt" are everywhere. "Lepers, cripples, the blind, and the idiotic, assail you on every hand." While Twain refused to prettify the Holy Land and had no patience with the preening piety of his fellow travelers, the experience moved him to an unexpected realization: "Christ knew how to preach to these simple, superstitious, disease-tortured creatures: He healed the sick."

Given the conditions in which these sad people eked out an existence, Twain expressed amazement that so many figures from the New Testament seem to have lived in well-maintained chapels, churches, and shrines of one kind or another. At Nazareth, he marveled at the Virgin Mary's living quarters, "where she and Joseph watched the infant Saviour play with Hebrew toys eighteen hundred years ago. All under one roof, and all clean, spacious, comfortable 'grottoes.'" In Bethlehem, he found the grotto at the Church of the Nativity to be "tricked out in the usual tasteless style" but was struck nonetheless to be where "the very first 'Merry Christmas!'" was uttered.

Twain regarded these and other sites important to Christians with mock solemnity. At the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, he was shown a niche that was said to have contained, at one time, a piece of the True Cross, discovered centuries before the Quaker City vacationers arrived. Their tour guides "say it was stolen away, a long time ago, by priests of another sect," Twain wrote. "That seems like a hard statement to make, but we know very well that it was stolen, because we have seen it ourselves in several of the cathedrals of Italy and France."

The travelers visited the Chapel of St. Helena, also at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where the cross, the nails, and the Crown of Thorns had been discovered. These, alas, had also disappeared—stolen, presumably. Priests of all denominations "can visit this sacred grotto to weep and pray and worship the gentle Redeemer," Twain noted. "Two different congregations are not allowed to enter at the same time, however, because they always fight." When one stands on the Hill of Calvary, "where the Saviour was crucified," Twain wrote, one "finds it all he can do to keep it strictly before his mind that Christ was not crucified in a Catholic church."

Christianity would be wonderful, Twain suggested, if it weren't for Christians. His opinion of his fellow travelers was not much better than those of the pitiable inhabitants of the Holy Land: He thought they were stuffy and hypocritical. One shipmate was a clergyman, pompous as only a 19th century New England clergyman could be. This man of the cloth, Twain said, "looks like he is waiting for a vacancy in the Trinity."

Twain was by no means a spoilsport, party pooper, or killjoy on the excursion. He played cards with the others; he played shuffleboard; he danced and drank. But he found most of them almost insufferable. Taken together, they constituted a "strange menagerie of ignorance, imbecility, bigotry & dotage," making it irresistible for him to record "how that curious company conducted themselves in foreign lands." They could be "so mean, & so vicious, & so outrageous in every way," that this accomplished swearer "could not collect the terms to express it [in] any less than sixteen or seventeen languages," he told a friend. That last vituperation is found in Twain's private letters, not in The Innocents Abroad, but even there, in an almost offhand way, he tells how these God-fearing people weep at sites sacred to their faith, then routinely pillage them of relics as souvenirs.

Twain would see this played out on a vastly larger scale in years to come. He would emerge, in the period of the Spanish-American War, as an outspoken anti-imperialist, denouncing efforts to "uplift" less fortunate peoples while imprisoning and killing them, annexing their lands and plundering them of their resources. On the Quaker City trip, Twain had seen this "stately matron named Christendom," as he would put it in The New York Herald, for what she was. Of course, there wasn't much for this stately matron to exploit in Palestine when Twain was there, though there would be in years to come.

It would be instructive to know what Twain would make of President Donald Trump's wishes to turn Gaza into a combination Las Vegas and Disneyland for the profit of American investors. I suspect he would not approve. He had seen up close and personal how Americans too often conduct themselves overseas and did not find the spectacle edifying. (Trump's favorite predecessor, incidentally, is President William McKinley, commander in chief during the Spanish-American War.)

Of course, Twain himself profited handsomely from the book he wrote based on his Quaker City adventures. He offered no apologies for this. The Innocents Abroad was a bestseller, putting the bachelor in a position to take a bride. "I want a good wife," he told a shipmate. "I want a couple of them if they are particularly good." The prospective family man discussed the matter with another passenger, an amiable young fellow from Elmira, New York. This was Charley Langdon, the son of a well-established New England coal baron. Langdon showed Twain a miniature portrait of his sister, Olivia. Twain was smitten.

Back on terra firma, a meeting was arranged. "I'll harass that girl and harass her till she'll have to say yes!" he told another friend. In time she did. It was a long and happy marriage, and she accompanied him on the worldwide lecture tour that he wrote about, years later, in Following the Equator. Twain, with all his opinions, could not have been the easiest traveling companion, but he was an entertaining and—as future generations can see—perceptive one.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Mark Twain in the Old World."

Show Comments (20)