South Park's Trump Takedown Joins a Proud American Tradition

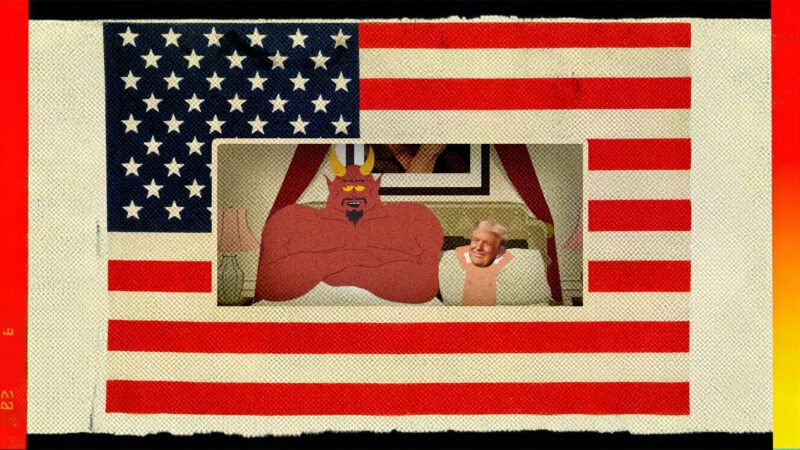

The cartoon’s savage Season 27 premiere puts a tiny, naked Trump in bed with Satan—and lands squarely in the American tradition of using outrageous satire to hold the powerful accountable.

The Season 27 premiere of South Park—the animated Comedy Central show famous for skewering public figures with crude and topical humor—trained its sights on President Donald Trump with the message that the would-be emperor has no clothes. Literally.

The episode depicts an out-of-control president who threatens everyone in sight with frivolous lawsuits, including the residents of South Park, merely for questioning him. Trump's cartoon doppelgӓnger cows the news program 60 Minutes into craven servility, whose reporters tremble when covering the fictitious case against South Park and take care to assure viewers what a "great guy" the president is.

And that about does it for the tasteful part.

The show's creators, Matt Stone and Trey Parker, portray a naked Trump with a tiny penis in bed with Satan, who asks about Trump's place in the Epstein files before rebuffing the president's sexual advances. The episode concludes with what appears to be an AI-generated public service video—inspired by a concession Trump claims to have extracted in the Paramount settlement—showing an obese Trump disrobing as he lumbers through a desert, ending with a close-up of his tiny talking penis (who endorses the ad).

The White House isn't happy. Assistant Press Secretary Taylor Rogers said South Park "hasn't been relevant for over 20 years and is hanging on by a thread with uninspired ideas in a desperate attempt for attention." To be fair, perhaps Rogers didn't know that Parker and Stone had just signed a $1.5 billion deal with Paramount for five more seasons of the award-winning show.

The feeble jab about relevance is laughable. The premiere packed in several hot-button issues in just over 20 minutes: Trump's addiction to baseless litigation, his abuse of regulatory power to force settlements, the spineless corporations that give in, the firing of Stephen Colbert, Trump's relationship to Jeffrey Epstein, the tariff dispute with Canada, and more.

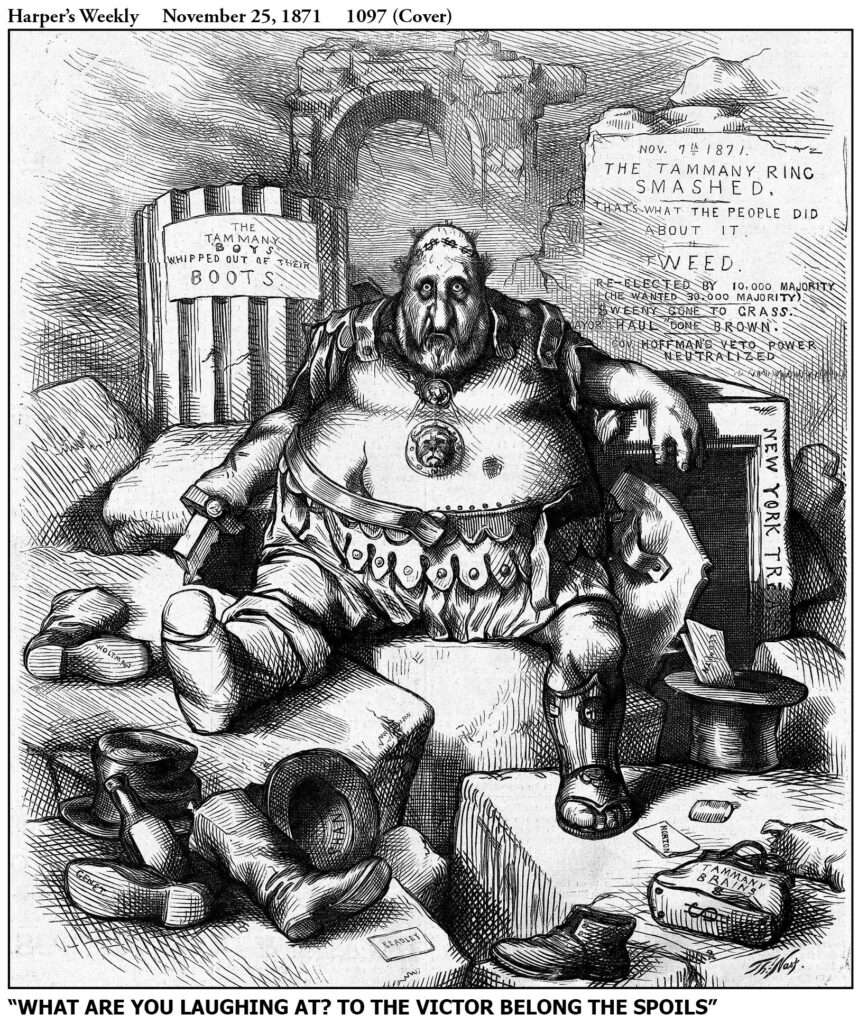

This kind of satire has long been a potent antidote to political corruption in America, perhaps best illustrated by the downfall of Tammany Hall, a corrupt Democratic machine that dominated New York City after the Civil War. It was run by the notorious William "Boss" Tweed, whose openly corrupt organization, "The Ring," collected millions of dollars in illegal graft. Newspapers had covered the scandal, but the public really took notice because of the work of Thomas Nast, the political cartoonist for Harper's Weekly.

The Supreme Court has described Nast as "probably the greatest American cartoonist to date," whose sustained attack on Boss Tweed and his organization "stands alone in the history of American graphic art." His vendetta against the corrupt machine succeeded because of the "emotional impact of its presentation" and because Nast aggressively pushed "beyond the bounds of good taste and conventional manners." Journalist and historian Robert McNamara wrote that "Thomas Nast depicted [Tweed's] rampant thievery in ways anyone could understand."

Tweed himself understood the power of using art and humor against political corruption, of which he reportedly said, "I don't care a straw for your newspaper articles, my constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures."

Then as now, the abuse of power was explicitly transactional. First, in a bid to stop "them damn pictures," Tweed tried to bribe Nast, offering what would be millions of dollars today for the cartoonist to study art in Europe. Nast turned him down flat, so Tweed and his cronies tried to strong-arm Harper's Weekly, threatening to have the city's Board of Elections boycott Harper's textbooks. Unlike Paramount today, Harper's ignored the threat and stood behind Nast.

The political potency of cartooning persuaded the Supreme Court to unanimously affirm First Amendment protections for Hustler Magazine in 1988 after Rev. Jerry Falwell sued it for causing "emotional distress" after the magazine published a savage and salacious parody of Falwell committing incest with his mother in an outhouse. The Court was untroubled by the "caustic nature" of the graphic attack, observing that "from the early cartoon portraying George Washington as an ass down to the present day, graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played a prominent role in public and political debate." It noted that political cartoons have "an effect that could not have been obtained by the photographer or the portrait artist," and accordingly, "our political discourse would have been considerably poorer without them."

South Park's gleeful takedown of Trump falls squarely within this tradition. And, perhaps for that reason, the White House and its political minions apparently have declared war on comedy.

Of Paramount Global's decision to terminate The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, the president posted, "I absolutely love that Colbert got fired. His talent was even less than his ratings." The company has maintained that the termination was purely for economic reasons, but the timing is suspicious to say the least, coming just days before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) finally approved the long-delayed Paramount-Skydance merger. Democratic FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez denounced the merger approval and said it resulted from backroom dealing that led to a "payout and other troubling concessions Paramount made to settle a baseless lawsuit."

Trump's post about Colbert, and his follow-up musing that Jimmy Kimmel could be next, was mirrored shortly thereafter by an FCC submission from the Center for American Rights. This political group that litigates on Trump's behalf is calling for the commission to investigate late-night talk shows to determine whether the shows and their comedian hosts are too left-wing. To this, Trump's hand-picked FCC chairman, Brendan Carr, suggested that maybe it is time for what he called a "course correction" for late-night television. Carr did not elaborate on what he meant by that—a fairness doctrine for comedy, perhaps?

It appears that Trump and his followers want to accomplish what Boss Tweed could not—to find a way to stop "them damn pictures" and jokes. But that's not going to happen so long as our leaders continue to beclown themselves, and our constitutional history teaches that it is the comedians like Colbert and the creators of South Park who will have the last laugh.

Show Comments (58)