Missouri Town Wants To Seize Local Businesses Over Chipped Paint and Cracked Sidewalks

Brentwood business owners are challenging the city’s definition of blight in an ongoing lawsuit against city officials' use of the dubious designation to invoke eminent domain.

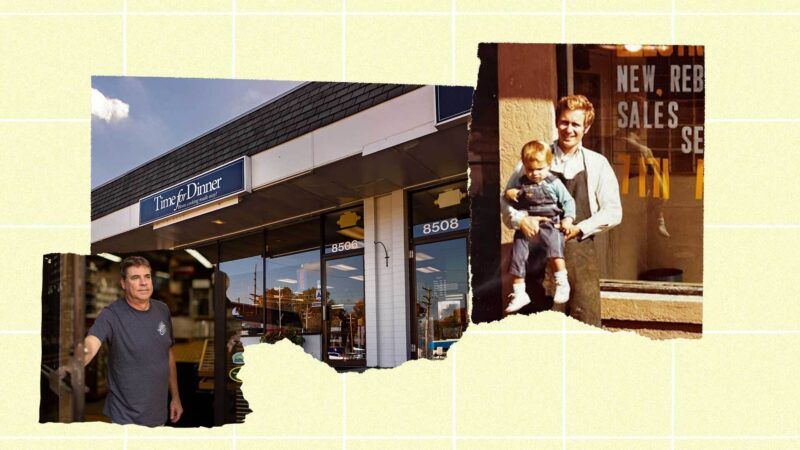

For 20 years, Amy Stanford and her sister Carolyn Wilson have run Time for Dinner, a family-oriented meal prep business that has served generations of local families in Brentwood, Missouri. Now she's one of several local small business owners suing the city over its decision to label their properties "blighted"—a designation that opens the door to property seizure for its sweeping $436 million redevelopment plan.

The ongoing lawsuit, filed in December 2023 by the Institute for Justice (I.J.), says the city is abusing its power by invoking eminent domain to push out businesses under a dubious blight designation. Under Missouri law, eminent domain can only be used for a legitimate public purpose, and invoking it for private or economic development purposes is prohibited. Cases of dispute over public use require a judicial determination "without regard to any legislative declaration that the use is public."

In July 2023, the city approved a plan to redevelop the Manchester Road Corridor with new office buildings and apartment complexes. City leaders argued that the redevelopment project was necessary to address persistent problems like flooding and crime and to generate new tax revenue.

The city has used a 2023 study by PGAV Planners, an urban planning firm, to justify its blight designations. The city-commissioned study found that 48 of the 75 properties in the redevelopment zone exhibited "physical deterioration," while 26 were vacant, enough to designate the entire corridor blighted.

Bob Belden, I.J.'s lead attorney on the case, argues that the study fails to prove that the area showed a "predominance" of unsafe conditions, as required by Missouri law in order to deem an area blighted.

The 2023 study lacked individual property analysis and included only 40 photos for 75 properties. Some properties had multiple pictures, others had none. Addresses weren't provided for the photos, some of which featured little more than an unidentified parking lot. Several pictures showed properties with cracked pavement, while other properties, like Time for Dinner, were not photographed and had no evidence of blight presented.

I.J. has contested the evidence in this survey in court, as well as a 2018 blight study conducted by the same firm that Brentwood has used to defend its actions. That year, the city kicked off an $80 million flood mitigation project along Manchester Road, which was deemed a success by Brentwood Mayor David Dimmitt in 2022. During the trial, which began in May of this year, the city used the area's state before the project commenced as evidence of blight.

Belden contends that the city should not be able to retroactively find justifications for the blight designation using the 2018 survey. The city disagrees.

The city also wrongly cited building age (which can't be considered in a blight determination as of 2021) as evidence of blight during the trial, relying on speculative claims about hazards rather than actual proof.

Speaking with Reason, Belden says Brentwood's eminent domain claim is invalid because the city's blight definition, based on minor issues like peeling paint and driveway cracks, no longer meets Missouri's standards. State statute says that an area can only be deemed blighted if it has a predominance of unsafe conditions, deteriorated site improvements, fire hazards, or other issues that hinder housing or endanger public health, safety, or welfare.

"What the city did here instead was if it identified one instance of peeling paint or a crack in the parking lot, it would find the property 100 percent blighted," he says.

Photos of Brentwood landmarks like City Hall and the police department were shown to the city's blight consultant, a PGAV employee who conducted the study, during the trial, alongside a Target store with minor loading dock damage. When asked if these properties could be blighted, the consultant agreed, noting cracks in the parking lot at the police station. Dave Phillips, a Minnesota architect and property inspector for over 40 years, testified that using the city's blight criteria, virtually any property could be deemed blighted, including 70 percent of Brentwood's housing stock under the city's building-age standard.

Carter Maier, co-owner of Convergence Dance and Body Center, tells Reason he was initially supportive of the redevelopment plan until he realized the scope of the project. "We really like being here….We like our neighbors. We like the community," says Maier. "We're all for development and redevelopment, but not in a forced way that Brentwood City Hall is trying to do."

Martin George, a landlord who initiated the lawsuit and owner of the building housing Feather Craft Fly Fishing, shared his motivations with Reason: "My own elected Alderman didn't represent me, they represented their Mayor." It was a frustration shared by Carolyn Wilson, who tells Reason, "[It's] very obvious that the city had decided before they started any of this, exactly what they were going to do….They weren't trying to find an alternative way to do it. And that's the frustrating part….There are other options."

Business owners had believed their problems were solved after the city's previous flood-mitigation project, Brentwood Bound, which built flood walls and improved streets.

Amy Stanford disclosed to Reason that the project significantly disrupted their business and customer access. "One bridge was rebuilt, and the road was closed completely for five months, so that was a mess."

Since Brentwood Bound's completion, "things look even better than before," Maeir stated.

It's what makes the city of Brentwood's eminent domain claim so asinine, and why critics have described it as an unconstitutional land grab.

The Brentwood City Mayor's Office, several members of the Brentwood Board of Aldermen, and Halo Real Estate Ventures, the chosen developers for the project, did not respond to Reason's request for comment.

The trial concluded on May 9 with a bench trial. After the trial, the city moved for a directed verdict, arguing a lack of sufficient evidence. I.J. has filed a motion in opposition. Once the trial transcript is shared with both parties, they'll have 30 days to submit proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law, with a decision anticipated by late August.

Show Comments (12)