Liverpool Lost Its U.N. World Heritage Status. Now It's Thriving.

The English city protects its historical sites while embracing growth and redevelopment.

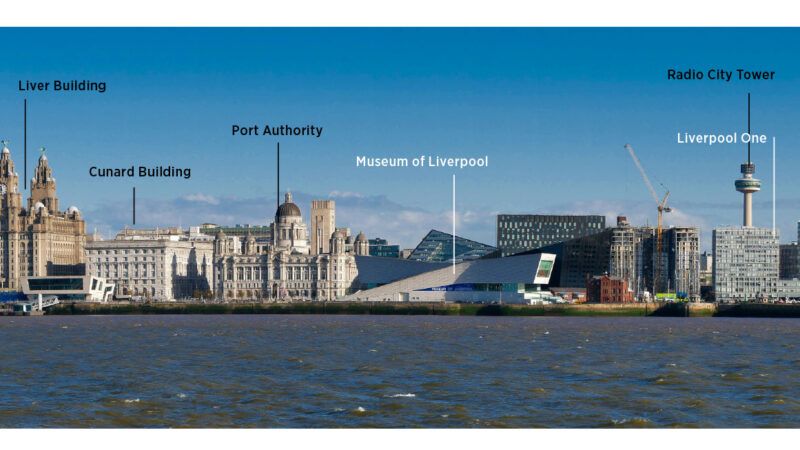

In 2021, Liverpool made global headlines when the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) revoked its World Heritage status, citing new development along the waterfront as causing the "serious deterioration and irreversible loss" of the area's historic value. Losing UNESCO's designation, though, only fueled the city's commitment to preserving its heritage while embracing growth.

The Royal Albert Dock is one of Liverpool's most iconic landmarks. When it first opened in 1846, it revolutionized global trade with its innovative design. Constructed entirely from cast iron, stone, and brick, the dock became the world's first noncombustible warehouse system. It was equipped with the world's first hydraulic cranes, halving the time to load and unload ships. The dock quickly dominated world trade, handling valuable cargo such as cotton, silk, brandy, and tobacco.

But just 50 years later, advances in shipping technology rendered the docks obsolete. After serving as a base for the British Atlantic Fleet and suffering damage during World War II, the dock sat neglected for decades—until its revitalization. In 1982, a regeneration deal transformed the dock into a vibrant hub of commercial, leisure, and residential activity. The site was restored, warehouses were repurposed into shops, restaurants, and museums, and the waterfront was reborn as a cornerstone of Liverpool's identity.

Liverpool received UNESCO World Heritage status in 2004. The designation recognized the city's historical significance in world ports and architecture, placing it in the same category as the Great Wall of China and the Taj Mahal. Liverpool's heritage site was divided into six areas, with the waterfront—home to the Royal Albert Dock—holding particular importance. In total, 380 features and 138 hectares (about 340 acres) were protected under this status.

Nearly two decades later, Liverpool became the third city to lose its World Heritage status, following the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary in Oman and Dresden's Elbe Valley in Germany. UNESCO argues that years of development irreparably damaged the Victorian waterfront. Initial objections arose when plans were unveiled to transform the docks north of the Royal Albert Dock into a mixed-use development, which UNESCO believed would threaten the site's heritage criteria.

Tensions escalated with the proposal to build Everton Football Club's approximately $973 million stadium in the north docks—an area that had been in decline for decades. The project's backers promised to revitalize one of Liverpool's poorest neighborhoods while preserving historical elements of the docks. But plans for the 52,888-seat stadium included partially filling in one of the historic docks—a move UNESCO deemed unacceptable. The stadium would significantly alter the city's skyline, the agency insisted, and lead to a "serious deterioration" of Liverpool's historical identity. In a 13–5 vote, UNESCO removed Liverpool from the World Heritage register.

Joanne Anderson, Liverpool's mayor at the time, called UNESCO's decision "incomprehensible," arguing that the organization would prefer to see a "derelict wasteland" than new development that could bring jobs and visitors to the city. Steve Rotheram, the metro mayor of the Liverpool City Region, said the decision didn't "reflect the reality of what is happening on the ground," emphasizing that Liverpool shouldn't have to choose between heritage and regeneration. After all, other historically significant sites, such as the Tower of London, have retained their World Heritage status even as high-rise construction has altered their surroundings.

Anderson noted that, at the time of UNESCO's decision, Liverpool's heritage sites had "never been in better condition, benefiting from hundreds of millions of pounds of investment across dozens of listed buildings and the public realm." In 2021, only 2.5 percent of the city's historic buildings were in disrepair, compared to 13 percent in 2000.

Despite the UNESCO delisting, Liverpool remains steadfast in its efforts to preserve the city's historical sites while embracing urban regeneration projects. Many ongoing developments are set to be completed in 2024, including the revitalization of the Canning Dock. Other projects are set to break ground soon.

As the Liverpool City Council proudly asserts, the city might have lost its UNESCO designation, but it remains the "supreme example of a commercial port of the time of Britain's greatest influence." Alan Smith, Liverpool's head of heritage preservation and development, declared that the city "didn't need" the heritage designation. "UNESCO may take our status, but you will never take our buildings," he added.

The Royal Albert Docks are a prime example of how Liverpool has successfully blended historic preservation with modern development. Studies show that repurposing the dock had minimal impact on its heritage value and, in some cases, even helped protect and enhance it. Instead of being abandoned, the docks are a vibrant destination where visitors can experience their rich history while enjoying a cup of coffee.

While UNESCO may have preferred that certain areas remain unchanged, the evolution of the waterfront continues to be central to Liverpool's cultural and economic life. Today, the area boasts several attractions, including the Merseyside Maritime Museum, Tate Liverpool, The Beatles Story Museum, and the International Slavery Museum. The area is also a bustling hub of hotels, restaurants, and shops, and a popular stop for the city's tourist hop-on hop-off buses.

Since losing its heritage status, Liverpool's tourism industry has grown by 21 percent, contributing $8.1 billion to the local economy. The city's job market has also grown by 13 percent since 2022, a testament to the city's ongoing growth and resilience.

Liverpool's identity continues to evolve, with the Royal Albert Dock at the heart of this transformation. The city has shown that it's possible to honor the past while building for the future—a balance that many cities aspire to but few achieve as seamlessly as Liverpool.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "No Longer a World Heritage Site, Liverpool Evolves and Thrives."

Show Comments (29)