This Mom Was Jailed for Leaving Her Teen Home Alone. Now, She's Suing.

An appeals court rejected a qualified immunity defense.

More than four years after two police officers arrested and jailed a mom in Midland, Texas, for leaving her 14-year-old daughter home alone, the family finally has the green light to sue them both, a federal court ruled last week.

Midland Independent School District Officer Kevin Brunner is not entitled to qualified immunity for allegedly violating the Megan and Adam McMurrys' 14th Amendment rights—and their daughter Jade's Fourth Amendment rights—when he removed Jade from her home and refused to let her call her father. So too may the family sue Officer Alexandra Weaver, Brunner's subordinate, who was deprived of qualified immunity by a lower court and did not appeal.

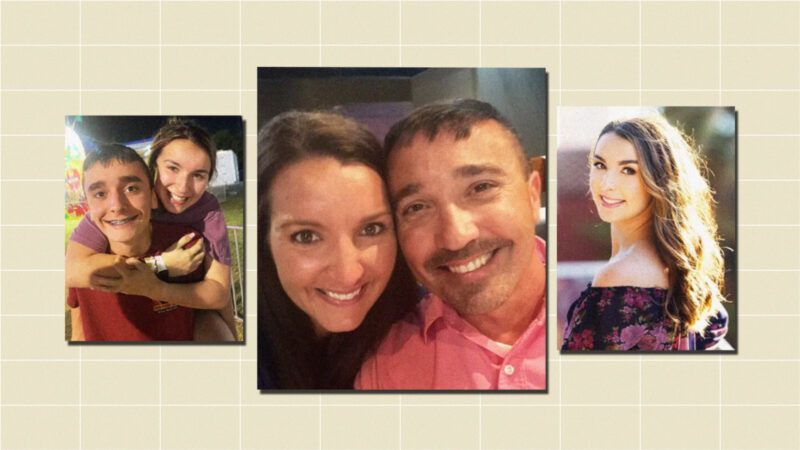

In October 2018, Megan McMurry left for a brief trip to Kuwait. Her husband was to be stationed there for the foreseeable future with the Mississippi Army National Guard, and McMurry, a schoolteacher by trade, made the trek to meet with a local school to perhaps reunite the family overseas. Her neighbors, Vanessa and Gabe Vallejos, in their gated apartment complex offered to watch her two children—Jade, then 14, and Connor, then 12—while she was gone for a few days.

What should have been a benign trip turned into the beginning of a legal odyssey.

When another neighbor, a school counselor, couldn't drive Connor to school as planned, the counselor asked Weaver to take him. Weaver couldn't oblige, so someone else took him. But Weaver didn't stop there, putting an investigation in motion, alerting Child Protective Services (CPS), and going with Brunner to the family home to do a welfare check on Jade, who did online homeschooling. After Weaver conducted a warrantless search, they removed her from the home and took her to Connor's middle school for an interrogation while refusing her multiple desperate pleas to get in touch with her dad. Body camera footage shows her sobbing.

CPS closed the case after they were apprised of the details; particularly rich is that the cops breached protocol when they refused to contact the parents, which is supposed to be first priority. But the police continued pursuing McMurry, despite that the agency in charge of such matters had cleared her. The cops charged her with two felony counts of child abandonment, after which point she spent 19 hours in jail. She was placed on unpaid leave from her teaching job, supposedly until the ordeal concluded, though she was ultimately fired.

At trial, about a year later, she was acquitted in five minutes. Her battle for a remedy in the other direction, however, has taken years, and it's still barely begun. Though Weaver now works in financial services at a local hospital, Brunner is a lieutenant in the same police department. Last week's court ruling may finally set some sort of public reckoning in motion.

Those familiar with qualified immunity may know that the court's conclusion was not necessarily foregone. The doctrine shields local and state government actors from lawsuits (such as the McMurrys') if there is no court precedent on the books with very similar facts that rules very similar conduct unconstitutional. An officer may violate his own training and still receive qualified immunity. The idea is that civil servants need fair notice when they are violating the Constitution, although it's puzzling that we expect them to read case law and not their departmental guidance.

Potentially problematic for the McMurrys is that not everyone agrees there was a relevant, identical precedent on the books to avail them. But problematic for Officer Brunner, whose case was the only one before the court this time, is that his actions were so egregious that the McMurrys didn't necessarily need applicable case law. It should've been that obvious to him that what he was doing was unlawful.

"Weaver performed an illegal search in front of her supervisor (Brunner). And instead of settling for one constitutional violation (the search), Brunner went on to commit two more (unlawfully seizing JM and violating the McMurrys' due-process rights)," wrote Judge Andrew Oldham of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit in a concurring opinion. "After taking custody of JM, Brunner prevented [Jade] from talking to her father and the Vallejos for a significant amount of time. All while [Jade] was crying and confused. Then CPS told Brunner that his safety concerns were baseless. And still, inexplicably, Brunner persisted and pushed for criminal charges against Mrs. McMurry."

Quite the saga. Recourse for the McMurrys is still not a given; defeating qualified immunity merely gives them the opportunity to state their case before a jury. The family may be in luck, however, if it's anything like the jury at McMurry's criminal trial, who will likely hear not only about Brunner's and Weaver's misconduct, but also the harms McMurry suffered as a result: a lost job, a day in jail, and the trauma around that—all for daring to leave a teenager by herself.