The Defeat of a Kansas Ballot Initiative Shows That Red-State Voters Don't Necessarily Favor Abortion Bans

The amendment lost by a surprisingly wide margin in a state where Republicans far outnumber Democrats.

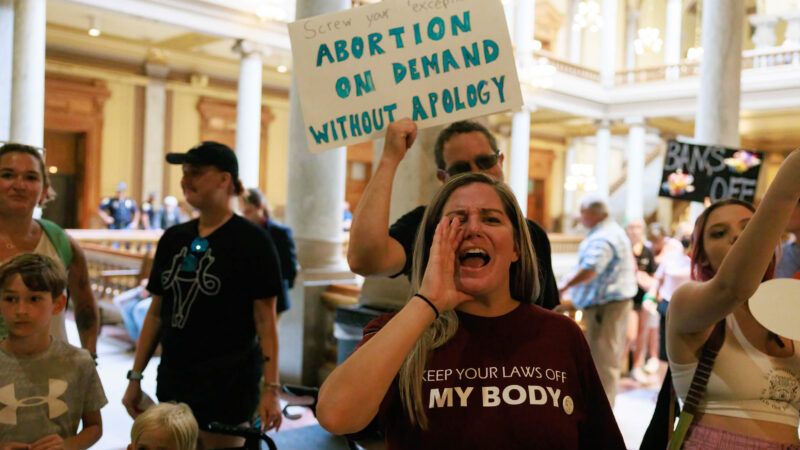

By a surprisingly wide margin, voters in Kansas yesterday rejected a proposed constitutional amendment that would have allowed legislators to ban or severely restrict abortion. The Kansas election was the first time that voters had a chance to cast ballots on this issue since the Supreme Court's June 24 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that established a constitutional right to abortion.

The amendment's defeat is significant in practical terms, since Kansas is located near several states that already have enacted abortion bans. It is also significant politically, since it suggests that voters do not necessarily support such laws even in red states where legislators are inclined to approve them. The post-Dobbs legal landscape will depend not only on state-by-state variations in public opinion but also on the strength and complexity of voters' views on the subject, which are more nuanced than the stark contrast between "pro-life" and "pro-choice" suggests.

The amendment that Kansas voters rejected would have overturned a 2019 decision in which the Kansas Supreme Court said the state constitution "affords protection of the right of personal autonomy, which includes the ability to control one's own body, to assert bodily integrity, and to exercise self-determination." The court said that right, in turn, "allows a woman to make her own decisions regarding her body, health, family formation, and family life—decisions that can include whether to continue a pregnancy."

According to the ballot summary, the amendment would have "affirm[ed] there is no Kansas constitutional right to abortion." That phrasing was clearer than the amendment's actual language:

Because Kansans value both women and children, the constitution of the state of Kansas does not require government funding of abortion and does not create or secure a right to abortion. To the extent permitted by the constitution of the United States, the people, through their elected state representatives and state senators, may pass laws regarding abortion, including, but not limited to, laws that account for circumstances of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest, or circumstances of necessity to save the life of the mother.

Despite the mention of possible exceptions and the reference to limits imposed by the U.S. Constitution, the amendment would have authorized a complete ban on abortion—a point that voters seem to have recognized. After a campaign in which each side spent around $6 million, a poll of "likely voters" conducted just before the election found that 47 percent planned to vote for the amendment, while 43 percent planned to vote against it and 10 percent were undecided. Given the poll's margin of error, those results suggested that voters were about evenly divided on the issue, and press coverage the day of the election predicted that the outcome would be close one way or the other. But in the event, 59 percent of voters opposed the amendment.

That result is striking in light of the state's partisan profile and earlier polling on abortion. Kansas has a Democratic governor, but Republicans control both chambers of the state legislature, where they have veto-proof majorities. Registered Republicans outnumber registered Democrats by nearly 2 to 1. Two-thirds of Kansas Republicans describe themselves as conservative. And in a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 49 percent of Kansas adults said abortion should be illegal in "all" or "most" cases. By comparison, the share holding that view was 59 percent in Mississippi at one extreme and 22 percent in Massachusetts at the other.

As Reason's Elizabeth Nolan Brown notes, the Republican legislators who put the abortion amendment on the ballot thought they were maximizing its chances by presenting it to voters in a primary election. Because Democratic primaries in Kansas are frequently uncontested, Republican turnout tends to be stronger. But the abortion initiative seems to have substantially boosted voter turnout, which in recent primary elections ranged from 20 percent in 2014 to 34 percent in 2020.

The Kansas secretary of state has not reported the overall 2022 turnout yet. But based on the results reported with 95 percent of ballots counted, it looks like statewide turnout was close to 50 percent. The Kansas City Star reports that 54 percent of registered voters cast ballots in suburban Johnson County, the state's most populous county. That sort of turnout, the Star says, is "nearly unheard of in a primary election."

The election results suggest that opponents of the abortion amendment were especially motivated to vote and/or that late deciders were inclined to vote no. Those factors could be enough to explain the unexpectedly large margin of defeat in a state where nearly half of adults (49 percent) told Pew they thought abortion should be legal in "all" or "most" cases. In Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and West Virginia, by contrast, the share of respondents who endorsed that position was 40 percent or less.

In 2019, all seven of those states enacted bans covering the vast majority of abortions. This November, Kentucky voters will consider a ballot initiative that, like the Kansas measure, would amend the state constitution to say nothing in it "shall be construed to secure or protect a right to abortion." That change seems much more likely to be approved in Kentucky, where just 36 percent of respondents told Pew they thought abortion should be legal in "most" or "all" circumstances.

Have voters' views changed now that Dobbs has freed states to restrict abortion? Maybe. A July survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) found that 51 percent of adults in states that had pre-Roe abortion bans or "trigger" bans designed to take effect after Roe's reversal said they wanted legislators to "guarantee abortion access." But those states included several where public support for abortion bans fell short of a majority even in 2014.

As Nolan Brown notes, the results in Kansas, where voters were presented with a single issue, do not tell us how people will vote in elections involving many other issues. The fact that most voters in a given state don't want legislators to ban abortion does not necessarily mean they will reject candidates who support such laws. That depends on whether voters see abortion as the paramount issue in a particular election.

In the KFF survey, 55 percent of respondents said "abortion access" was "very important" in deciding how to vote this fall. While 77 percent of Democrats said that, just 33 percent of Republicans and 48 percent of independents agreed. Overall, 43 percent of respondents said Dobbs had made them "more motivated" to vote in November. That included 64 percent of Democrats, 41 percent of independents, and 20 percent of Republicans.

Given the wide geographical variation in opinion about abortion, national polling does not tell us much about how legislation will play out state by state. But it does show that Americans cannot be neatly divided into two sides, one favoring sweeping bans and the other opposing all restrictions.

In the most recent Gallup poll, conducted last May, just 13 percent of respondents said abortion should be "illegal in all circumstances," while 35 percent said it should be "legal under any circumstances." A plurality of 50 percent said abortion should be "legal only under certain circumstances." That middle view covers a wide range of policies, from strict laws with a few narrow exceptions to liberal laws that allow nearly all abortions.

While 39 percent of respondents described themselves as "pro-life," 56 percent opposed a ban on abortion after 18 weeks of gestation. Based on 2019 data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, such a law would affect less than 3 percent of abortions. A 15-week ban like the one at issue in Dobbs likewise would affect a small share of abortions: a bit more than 4 percent.

By contrast, a ban on abortion after fetal cardiac activity can be detected, which typically happens around six weeks, would apply in the vast majority of cases. Counterintuitively, Gallup found that opposition to such a law was only slightly stronger than opposition to an 18-week ban: 58 percent. Still, a substantial percentage of people who described themselves as "pro-life" nevertheless opposed restrictions ranging from moderate to severe.

By the same token, people who identify as "pro-choice" are not necessarily opposed to all restrictions on abortion. Even states where pro-choice sentiment is strong and elective abortions are generally legal often restrict abortion after a certain cutoff, typically 22 to 24 weeks. In 2018, when 48 percent of Gallup respondents identified as "pro-choice," 77 percent said elective abortions should be illegal in the third trimester, although most thought there should be exceptions "when the woman's life is endangered" or "when the pregnancy was caused by rape or incest."

When asked about first-trimester abortions, 45 percent of respondents said they should be legal "when the woman does not want the child for any reason," while overwhelming majorities (83 percent and 77 percent, respectively) said they should be legal to preserve a woman's life or in cases involving rape or incest. Since 46 percent of respondents described themselves as "pro-life," many of them supported those exceptions.

These findings suggest that middle-ground abortion policies could be politically viable in some states. In Florida, for example, 56 percent of respondents told Pew they thought abortion should be legal in "all" or "most" cases. That position could be consistent with a 15-week ban like the one Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law last April. By contrast, a six-week ban, let alone a ban beginning at conception, would not be supported by most Floridians.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Shockingly, not everyone is as black and white with abortion as the MSN would lead you to believe.

I made $30,030 in just 5 weeks working part-time right from my apartment. When I lost my last business I got tired right away and luckily I found this job online and with that I am able to start reaping lots right through my house. Anyone can achieve this top level career and make more money online by:-

Reading this article:> https://oldprofits.blogspot.com/

Apathy is worse than hatred. People who can’t be bothered to stand up for the right to life of the unborn.

What have people learned in the month since the Supreme Court ended 50 years or 63 millio legal murder? Not much.

I made $30,030 in just 5 weeks working part-time right from my apartment. tyh. When I lost my last business I got tired right away and luckily I found this job online and with that I am able to start reaping lots right through my house. Anyone can achieve this top level career and make more money online by:-

.

Reading this article:>>>> https://brilliantfuture01.blogspot.com/

I think the sad part is, you can't tell if the 'shockingly' is legitimate surprise or 'methinks the lady doth protest too much'.

Like, are Sullum, ENB, and MSN really that far out of touch with morals and human decency that they couldn't have considered this or is it a case of "Oh, this vote that we totally had nothing to do with and wanted to turn out a certain way turned out that way despite the fact that it was in a heavily Republican state and we totally had nothing to do with it because it surprised us too!"

The general claims of major policy victory by Biden in this vote (highlighting the 'Was it a suprprise or not?' schizophrenia) was hilarious too. The rejection of the ballot initiative returns Kansas to the group of States that, 6 mos. ago, would've pretty solidly been described as 'restrictive' on abortion.

Like, are Sullum, ENB, and MSN really that far out of touch with morals and human decency that they couldn't have considered this or is it a case of "Oh, this vote that we totally had nothing to do with and wanted to turn out a certain way turned out that way despite the fact that it was in a heavily Republican state and we totally had nothing to do with it because it surprised us too!"

I should add: I don't know or even believe the vote was rigged/influenced one way or the other. I just get that paranoid, gaslit, or even like (failed) guilt trip feeling about somebody saying, "I have no idea how the coffee got made this morning!"

Most pro-lifers tend to be pragmatic and realize that abortion bans are unenforceable and unlikely to achieve their desired outcome. They are willing to compromise, as this story indicates. They tend to be far more accommodating towards compromise than the pro-abortion advocates.

Safe, legal and rare should be the standard everyone should work towards. I'm pragmatically pro-choice while being morally pro-life. It is utterly disgusting and morally repugnant to celebrate abortions, however, laws shouldn't be the venue to enforce morality. I support bans after 15-17 weeks, except in very narrow circumstances, while also realizing that the majority of those circumstances abortion is often not the correct or safest option.

I'm pragmatically pro-choice while being morally pro-life.

That's a great way to put it, and I'm in agreement.

But how do you convince the "My body my choice" and "Abortion is murder" crowds to find middle ground?

I think the majority of abortion is murder crowd tend to be more open to pragmatic compromise. They're usually open to narrow exceptions, while also willing to discuss bans only after the first trimester, as they are often aware complete bans are unworkable.

And by same token, while I live in the SF Bay Area I know not one single person who thinks elective abortion in the third trimester should be legal.

Maybe. I'll admit my sample size is biased.

I've tended to see the push by those on the left for unlimited abortion more in a response to those on the right who want a total ban rather than actually thinking elective third trimester abortion is an appropriate thing.

Aye.

It's even been my experience that after presenting all the arguments for why abortion should never be forbidden at any point, if you ask directly "should elective abortion in the third trimester be legal" the answer is always "well, no." In the end, they think it should be allowed where the life of the mother is in danger or where the child is so deformed it won't live more than hours outside the womb in any circumstances, but no one I've ever come across thinks the woman should just be allowed to change her mind and decide to have an abortion in the third trimester.

Totally agree. Further - there just aren't many third trimester abortions in the few states where they are even allowed. Here's data that I think is pretty solid - for 2012 which this link says is the last year with data. This data is technically 21 weeks (second trimester) v 24 weeks (third trimester):

Alaska - 0

Colorado - 87

DC - Not reported but probably 0

New Hampshire - Not reported but probably 0

New Jersey - 734

New Mexico - 191

Oregon - 166

Vermont - 8

Total - 1,186

Only Colorado and New Mexico have clinics that even offer 3rd trimester - two in each state. Otherwise - it is only hospitals in those other states. Hospitals have never offered on-demand. Of those 1190 total, roughly half are probably second trimester abortions (21 to 24 weeks). But regardless - in almost no case is a healthy baby aborted.

The most likely cause (well over half and up to 80%) is a diagnosis of fetal anencephaly.

The second likely cause is family rape that has been covered up.

The remainder is extreme poverty - where a pregnant mother couldn't afford (or didn't know about) a 1st trimester abortion at $500-700 but can afford a 3rd trimester higher-risk abortion at $3000-$5000. Just the numbers tell you how rare that is going to be and the real cause is poverty and lack of maternal care unless the point is to blame the victim which is exactly what many commenters here want to do.

As an aside - a diagnosis of fetal anencephaly or similar also means 'viability' is a meaningless term. The fetus will die quickly if inducing birth. A delivery of a non-viable preemie is a very high medical risk for the mother. For those who have been diagnosed natally rather than after delivery, it would also mean three months of psychological torture knowing the outcome of delivery.

What is appalling - sociopathic really - is people distorting and lying about this in order to score political points.

It isn't a high medical risk. Both risk from labor and from abortion is far, far below, 0.1%.

Third trimester abortion.

Pregnancy involving a fetal abnormality (that is almost inevitably fatal) or alternatively a pregnancy involving a very poor mother with next to no pre-natal care.

Those are the relevant risks for a third trimester abortion.

A lot of ifs, and still not even close to a 1% chance of fatality. And how would you have a natal abnormality diagnosed if you've had no prenatal care. You're wrong. Period.

Finally, as I've pointed out several times the safety and health argument for abortions don't stand up to actual data and facts. Labeling people and demonizing them as you do above, is exactly why people who are willing to compromise, drift towards the extremes.

You are defending your side but demonizing the other side. Exactly as both Square and I've stated is how you end up with extremes, when most people have far more nuance than you give them credit for.

Besides bringing up third trimester abortions, is a red herring, as they are rare and it's extremely highly dubious if they are medically justified. You have to resort to a bunch of contradictory assumptions to try and justify them. Even while stating they are rare. And the Kansas proposed amendment did not even ban them, as it allowed the exceptions you argue are ignored but the 'heartless psycopaths' in the pro life movement.

Rather than attempting to even understand their position, you rather attack them. Which means you are as big, if not a bigger problem, than they are.

Also, the diagnosis of fetal ancephaly is not automatically fatal. It depends on the degree and which portion of the brain is missing. And even then, very few actually choose abortions, and even those who do, feel guilt about it.

So it doesn't really reduce the psychological torture of carrying a baby to term, as anyone who is at all familiar with natal deformities will tell you. By the third trimester, almost universally the mother has developed an attachment to the baby and the announcement that their child has some form of deformity is devastating to such a degree that abortion doesn't reduce this devastation. The stages of grief are experienced almost equally between those who seek an abortion and those who don't. So the psychological argument is less persuasive than the tenuous safety argument.

So, in essence, in your rush to demonize pro lifers you have created arguments not supported by the actual science, and ones often contradicted by the actual science. Additionally, you have opened yourself and your side to arguments about eugenics (should only perfectly healthy babies have a right to life). Once again proving my overall hypothesis, and ultimately Squares if I read him correctly, that the extremes and tribalism pushes people into the extremes.

soldier is full of shit. 3rd trimester abortions due to risks for the mother or the complete unviability of the fetus are indeed rare, but those are the reasons - not, "oh gee, I think I want to go that party on my due date, so scratch this pregnancy." I have close relative who worked in this at a major teaching hospital, including "genetic counseling" which is required treatment for older mothers who often have complications. These women/couples want to have a child and it's no fun for them to face the horrible reality.

Also, only about 10% of women seek abortions and most of them already have or plan to have children. The idea that this is primarily a right used by party girls is just wrong and assumes the overwhelming number of most women do not take pregnancy lightly, though of course a few do - no law or system is perfect and without it's downsides.

Lastly, soldier soft pedals pro-lifers as the reasonable side of this debate, when they are the ones wanting to make this difficult decision for everyone else, our modern day church ladies. Kansan's just told them to butt out.

Joe Faggot, adults are having a conversation here and you’re not even a real human, or intelligent.

So fuck off and play in traffic in the interstate. The adults are talking here.

And in my experience the pro-life crowd tends to only go to the extreme of total bans when they encounter those who oppose any regulations on abortions. Such as requiring them to have admitting privileges the same as what is required of every other same day surgery clinic.

This whole line of argument that one side's uncompromising fanaticism is somehow induced by, mitigated by, and/or justified by the other's reeks of BS and is anti-libertarian. At least you prefaced by admitting the flaws of your premise(s).

I think the majority of abortion is murder crowd tend to be more open to pragmatic compromise.

In my experience there is a strong overlap between that crowd and strong supporters of the drug war. They're all for prohibition and could care less about the consequences.

I think it's murder but who cares what I think not everyone needs to agree with me & if it's voted for in Kansas so be it

I just won't spend my money in Manhattan @Cats football games anymore lol

Go State!

Also, don't blame me... I didn't vote.

KSU comes to Texas a couple times a season it's great ... I'll be in Ames 10/8 too go Cats.

I support bans after 15-17 weeks, except in very narrow circumstances,

I am roughly the same except my timeframe is viability (roughly 20-24 weeks). Which apparently puts me firmly in the pro-choice 'you are advocating baby murder' camp - exactly where 43 of 50 states were pre-Dobbs.

What is so special about 15-17 weeks? Viability means something

See once again you misrepresent the vast majority of the pro life and try to frame the argument in such a manner as to create a false dichotomy where your position is the reasonable one. You use loaded language, both in describing your position, in order to state your being reasonable while others are extremists attacking you, and then by stating yours is reasonable because of viability (which is not a set number BTW, as the earliest preterm infant born and lived actually is before your limit) and that those who have a shorter period are not being reasonable.

But, to answer, because four months is more than enough time to make a decision that will result in the death of another person. Viability is also a tenuous argument. It changes with technology and also changes with usage. There is the common usage, and there is several abstract, but completely accurate biological and medical definitions. Viability can also mean a fetus that could more likely than not, develop far enough to be born alive, e.g. a tubal pregnancy is not viable, a extra uterine pregnancy is unlikely to be viable, though it's possible in real rare cases, whereas a uterine pregnancy is a viable pregnancy, barring some other complications, irregardless of it's ability to survive birth at that point in the pregnancy. Given these facts, babies born alive before 20 weeks, and surviving, advancements in medical care that makes these more likely every year, and the dubious nature of the term viable, I don't think your position is anymore defensible than mine.

I also take into account what the rules are in the vast majority of developed countries, which coincides with my position. And even further, I think my positions is more pragmatic in that it allows legal, safe abortions, and while morally reprehensible in the eyes of most pro lifers, also is a position they're willing to agree to, whereas waiting midway through the pregnancy is a step beyond what they are willing to agree to. So, as a matter of compromise, my position is more likely to be successful than waiting until either the middle or end of the second trimester.

Additionally, when we look at statistics the great majority of abortions occur before the 15th week, ergo, most people have made the decision to keep the baby after this time (which happens to occur around the same time as quickening occurs, and the data is really strongly supporting that almost no one seeks an abortion after quickening and those who do tend to have high levels of guilt afterwards). So, in order to push it back to your time frame you are purposely picking a position that will alienate even moderate pro-lifers, well also covering so few abortions as to be meaningless. It's a rather extreme position actually, as it creates animosity well providing very little benefits. If your position is based on the rarest cases, you aren't arguing for a pragmatic solution, your arguing for an extreme solution.

There is room to discuss fetal abnormalities and health concerns, but be aware that these arguments are not as concrete as you believe they are, and that it isn't extremists to point out the faults or dubiousness of these arguments.

I would also point out that the number of women choosing to get abortions dropped dramatically once they get their first ultrasound. This is not in support of forced ultrasounds, so much as an acknowledgement that those opposed to those laws dance around one of the biggest elephants in the room, that ultra sounds do dramatically reduce the number who choose abortions and this is at least some of the reasons some pro-abortionists oppose these procedures. Because human nature is hard to overcome, and as much as we try to render gender ambiguous, that the female mind, in the vast majority of cases, is wired to want to protect infants, that even pro choice women, when they perceive some connection to the fetus, i.e. ultrasounds or quickening, in the vast majority of cases can't bring themselves to get an abortion. No matter what their previous convictions were.

The trend in the western world has been decreasing abortions (there was a slight increase in 2020, but also many prenatal visits were cancelled or done via tele meetings and things such as elective ultrasounds were largely cancelled) as technology has made diagnosis and imaging more exact. That women who don't seek early prenatal care are far more likely to get an abortion than those who do so. This is one of the reasons that they are so opposed to Crisis Pregnancy Centers that offer prenatal care as option to abortion, because they do successfully prevent abortions. And for some of the extremists (not the majority of pro choice) anything that prevents abortions, even if it is just persuasion and providing early pre natal care free of charge, is bad. We can't pretend there isn't those on the pro life side who would ban abortions and anything possibly related to abortions, but they are a small minority, nor can we pretend that there aren't those on the pro choice side who not only feel abortion should be legal but actually want it pushed and celebrated. Well, I think this view is a distinct minority, it does tend to get more publicity (such as celebrating and getting a standing ovation at an awards show, your abortion). We can pretend that pro-life is more extreme but only if we ignore several celebrities and left talking heads. Both sides have their extremes, and if we only discuss the extremes we tend to push possible allies in reaching a pragmatic workable compromise towards the extremes. I see it all the time in these threads, where dishonest arguments or demonization often results in me backing the more extreme pro life arguments, despite my convictions on purely pragmatic grounds.

You covered that very well. Good work.

"which is not a set number BTW, as the earliest preterm infant born and lived actually is before your limit"

I guess if viability was a calendar event you would have a point. But since it isn't, you don't. Viability is a very clear standard. When it happens is variable (heck, just identifyomg an actual conception date has a range), but that doesn't make it arbitrary.

"But, to answer, because four months is more than enough time to make a decision that will result in the death of another person."

Except it isn't another person. You believe it is, but that is just your belief. Calling a fetus a person is loaded language, so you should probably put down your rock, Glass Houses. And your ignorant (meaning you don't know any actual information about the situation a person finds themselves in) arbitrary judgement as to the parameters of "more than enough time" is presumptive, to say the least.

"It changes with technology and also changes with usage."

No, it has a clear definition. It isn't when a fetus manages to survive, it is when a fetus is capable of surviving. A fetus at may not have functioning lings at 26 weeks, if ot develops slowly. No amount of technology available today (or any time soon) wouls allow that fetus to survive. It is impossible. On the other hand, a fetus has been morn at 21 weeks, 0 days and survived. The 26 week fetus wasn't viable. The 21 week fetus was. It's not hard to understand unless you don't want to. Or are trying to make it seem complicated.

"whereas waiting midway through the pregnancy is a step beyond what they are willing to agree to"

Your position is that people need to make their medical decisions based on what a bunch of strangers think is the "right" decicuon?

Then next time you have a medical decision to make, please post here so we can tell you what is the right decision. And don"t think you get to refuse our opinion because we know what's best for you.

"It's a rather extreme position actually, as it creates animosity well providing very little benefits."

There are two extreme positions. One, that a fetus is a person at conception and two, that a fetus isn't a person until their first breath. Everything else is some version of moderate.

Although the argument can be made that any intrusion into someone else's medical decisions, especially an arbitrary, moralistic intrusion, is pretty extreme to begin with.

"If your position is based on the rarest cases, you aren't arguing for a pragmatic solution, your arguing for an extreme solution."

Viability isn't "the rarest cases". It is literally the minimum requirement for life. 100% of live hunans have achieved viability. 0% of non-viable fetuses have. Said another way, 100% of non-viable fetuses have failed to become living humans. Said another way, without viability there is a 0% chance of life.

It's not arbitrary like the various pro-life positions, it doesn't require misrepresentation (like the "heartbeat without a heart" fallacy), and it doesn't require something as arbitrary as moral beliefs.

You pretend that your position is reasonable and anyone who doesn't agree is extreme. That would mean that over 50% (closer to 60%) of Americans are, by your definition, extreme. That's a terrible understanding if what the word "extreme" means.

Finally, your belief that the anti-abortion and pro-life side are more reasonable and open to compromise is belied by the draconian laws that are being passed across the country. The moment that abortion ceased to be an individual decision, the ones you think of as "reasonable" brought down the full power of the government hammer. Hell, they're trying to figure out how to punish people who travel sewhere to get an abortion.

That's not reasonable. That's not good. That's not right. That's not moral. And it is the antithesis of what America stands for.

People come here to escape religious persecution. People come here to escape government intrusion. People come here for freedom. America stands for (and with) those people. Unless they want an abortion. Then, anti-abortionists stand against those things.

Great, so someone giving you a post-term abortion is of no consequence to you apparently.

Viability is irrespective of whether it’s a person.

I'd say I'm pragmatically pro-choice and morally pro-life. I prefer the 'heartbeat rule'. I even think it should be modified to 'heartbeat and brainwave' rule (typically 8 weeks) even on a case-by-case basis. This is pretty standard fair for determining when an adult human has turned back into a clump of cells ready to have its organs harvested. Seems straightforward for determining when a clump of cells has turned into a human. It also, by a somewhat surprising-but-not-really-unpredictable twist turns out to be about the same time when 'plan B' pills stop being safe effective too.

It also, IMO, represents a critical point that reduces a lot of the morality and even personal beliefs/responsibility out of it. Does my right to swing my fist end at the vellus hair at the tip of your nose or when I alter your brainwave function? If I were swinging my fists wildly, would you want other people to intervene when my fist touches your nose or after I've permanently altered your brainwave function? It's obviously assault to punch a person in the face but punching a corpse?

I agree that safe, legal, and rare should be the standard, but I think lots of people speak that phrase with all kinds of false correlations, causation, and narratives in mind that have been baked in since the phrase was first uttered. Murder is 100% illegal in Chicago, we still get 6-800 per year. The case clearance rate is something like 30-40%, even from there murder convictions are well below the 20% of the 6-800 homicides seen every year. Even if we don't prosecute every last murderer, 100% is the goal with safety in mind. Further, as I've mentioned before, lots of people talk about "If you ban abortion, women will die." but much of that talk is a rather insulting anachronism that pretends that we've learned nothing about medical science, including abortion, in the last 50-70 yrs. and will learn nothing going forward. Even if there were some sort of impossible federal ban of abortions after 8 weeks, there would still be plenty of plan B pills to perform the safest abortions, legally. There would still be plenty of capable and sympathetic OB/GYNs that the government would be virtually powerless to convict outside of a fair definition of 'rare'. Everybody outside that would effectively constitute unsafe and illegal. Without the impossible federal ban, which I should note that I'm not favoring, almost certainly CA and NY and a couple of other states are going to continue to crank out doctors who are ready, willing, and able to perform any abortion, anywhere, any time, under any condition and if they fly out to the middle of flyover country to perform a back alley abortion with a coathanger, they should be prosecuted. If they have them admitted to their care and insurance covers the patient being transferred to CA or NY or wherever (or the family or doctor covers them out of pocket) where the abortion is performed in a clinic/hospital, no harm, no foul.

Well said! Government shouldn't legislate morality. Something that used to be quite common on the Right, but less so today, which is refreshing. Reasonable restrictions are a matter of ethics imo, and it seems that many people feel the same.

They tend to be far more accommodating towards compromise than the pro-abortion advocates.

This doesn't seem true to me. It seems to me like most people pick the most extreme and intolerant people on the other side to focus on, and ignore the people who are willing to compromise.

When one side takes the original decision and pushes it to the moment of birth, that does not leave much room for compromise.

The MS law that led to the Roe reversal had a 15 week time frame. For the choice folks, that wasn't enough.

"Legal up to the moment of birth" is a position with very little support, as is "illegal from the moment of conception."

But the anti-abortion crowd only want to talk about the first group, and the pro-abortion crowd only want to talk about the second group.

I'm just pointing out what the law that was challenged allowed for, and also noticing how multiple states kept pushing the timeline further and further. It doesn't seem like the anti crowd is as big a holdup, but I could be wrong. It has people who won't budge, too.

I'm just pointing out what the law that was challenged allowed for

And I think that's accurate - the activists on the pro-abortion side don't hear "15 weeks," they hear "abortion ban."

The anti-crowd has until now been prevented from being holdups by Roe v. Wade. Will they compromise now that they have a seat at the table? Maybe.

I think they're more likely now than before, because they pro side extremists can't sue any regulations proposed under their rather broad interpretation of Roe, which went far beyond what Roe actually allowed (which was far more in line with the Mississippi law). Yes, some states will initially enact restrictive laws, but as we have seen with marijuana legalization, even red states eventually moderate their stance due to pragmatism and the fact that the majority of voters tend to be far more pragmatic than their representatives. It won't be perfect, but far from the dystopia that the militant pro-abortion extremists predict.

Yes, some states will initially enact restrictive laws, but as we have seen with marijuana legalization, even red states eventually moderate their stance due to pragmatism and the fact that the majority of voters tend to be far more pragmatic than their representatives.

I think this is exactly right, and is why I'm actually optimistic that Roe v. Wade being gone will make this particular controversy less absolutely-central-to-everything.

Over time, federalism tends to lead to moderation and normalization. It likely would have even with slavery, but both sides extremists, sidestepped federalism and tried to push their desired outcome through central government fiat. Slavery already was growing less profitable in several slavery states (almost all of which except Tennessee and Virginia stayed with the Union). New York at the turn of the 19th century had the second largest slave population in the nation, for example. But government actions, such as the Missouri compromise, and the federal slave fugitive act, made a federalists solution impossible. Also, Eli Whitney didn't help matters, but I think the invention of the cotton gin is oversold, because Adam Smith was correct that chattel slavery is not a viable economic practice. That's why almost every culture that has practiced it eventually abandons it.

Adam Smith was correct that chattel slavery is not a viable economic practice. That's why almost every culture that has practiced it eventually abandons it.

And this is why I really do think we don't need our government to take action against Chinese malfeasance - I don't believe for a second that they way they do things is sustainable and that they would present real competition for an actually free economy.

New York at the turn of the 19th century had the second largest slave population in the nation, for example

That is utter nonsense according to the ACTUAL 1800 census

Virginia (eastern district) - 322,199 slaves

South Carolina - 146,151 slaves

North Carolina - 133,296 slaves

Maryland (incl DC) - 102,465 slaves

Georgia - 59,699 slaves

Kentucky - 40,343 slaves

Virginia (western district) - 23,597 slaves

New York - 15,602 slaves

Okay, may have had the year wrong, but at the time of the end of the revolution New York was the largest slave owning colony, which doesn't negate my other points.

And yet even in 1800 (15 states by that time) the were still number 8. So, from 1783 until 1800, they went from number two to number 8. Not due to government actions but due to free market and popular opinion, so this actually proves my point even more. Thank you for your gotcha, as it reinforces my original point.

Adam Smith was correct that chattel slavery is not a viable economic practice. That's why almost every culture that has practiced it eventually abandons it.

Buggy whips are non-viable economically - which is why they ceased to exist without the need for laws abolishing buggy whips.

AFAIK - there is not one country where slavery simply disappeared without laws abolishing the practice and an active abolition movement pushing for those laws. Cite one.

And Adam Smith did not think that slavery would be 'abandoned' - or abolished. Even if he thought it was immoral, grotesque, and economically inefficient.

Smith believed it was unsustainable and comparing a single piece of technology to a whole economic policy is completely asinine. Unsustainable means, btw, that eventually it will fail.

In fact Smith argued that only economic arguments would be successful in ending abortion, that moralistic arguments for abolition were doomed to failure. He did state that slavery was a natural part of the natural evolution of societies and cultures but that economic arguments eventually showed the fallacy of slavery and that societies drifted away from chattel slavery, while creating tyrannical states that placed many in the positions akin to slavery. However, in a free market society, that even these classes were capable of escaping slavery by upward mobility afforded by capitalism. And additionally that slavery actually stunted economic growth, even while it consolidated that wealth in a minority, and that free economies allowed greater wealth. This was proven in the south that was economically retarded (the actual meaning of the word not the derisive meaning) compared to the north, and that even the planter class became more wealthy after slavery ended.

Chattel slavery is only non profitable once machine labor in general is accessed. For the vast majority of the human races existence all tasks were done with manual labor.

Race* goddamn this needs an edit.

Even by the latter medieval states chattel slavery had become very scarce, long before the high middle ages, despite how much manual labor was required. Serfdom was not chattel slavery, nor was it evenly applied in even central and western Europe. And the amount of freedom differed greatly between locations even within the same country.

Also, this argument completely runs contrary to the Eli Whitney Theory. Slavery was actually on the decline in the south, prior to the invention of the cotton gin, and most intellectuals thought it would have died on its own, without this invention. Jefferson, Madison, Monroe and Henry all believed that slavery actually made the south poor and retarded economic growth. This is similar to what Smith argued in A Wealth of Nations.

Even serfdom tends to inhibit economic growth and is generally abandoned even before industrialization. Many of the successful Tsars viewed the abnormal continuation of Russian serfdom as contributing to it's economic retardation. Especially when compared to western and central European powers, like the Holy Roman Empire, which had largely abandoned even serfdom by the high middle ages.

England went even further, by centralizing and combining agriculture, before the industrial revolution, almost completely eliminating serfdom at the time, increasing farm production and creating a larger class able to start laying the foundation of what would become the industrial revolution. The Netherlands, after it's independence from Spain, and Scandinavia also implemented similar reforms, whereas France lagged behind. The result was that these northern countries were more economically strong than France, and capable of weathering even natural disasters and war better than France. While most of these nations did allow slavery in their colonies, few practices it domestically, even if it were legal.

It should also be pointed out that the countries that first introduced slavery into the colonies, also tended to be the countries that practiced serfdom the longest and resisted pre-modern economic reformation the longest, Spain and Portugal (which was part of Spain for a vast majority of this time). In fact, Spain by the end of the 16th century was lagging far behind their northern competitors despite having a near complete monopoly on several important industries, such as the North American Silver industry, and via their Philippines and Mexican colonies, the silk and Chinese porcelain trade. Read 1493 by Mann, it goes into the idea and growth of the slave trade in the Americas while also pointing out how it actually hindered economic growth for the colonies. Both of his books 1491 and 1493 I highly recommend as they are very insightful and dispell a lot of the common myths. For example probably the biggest reason slavery survived in the American south was yellow fever and malaria, which killed indentured servants and free European colonists at a faster rate than African slaves. He also discusses the Amerindian slave trade to a degree that most ignored and why this industry proved so short (again it has to do with disease introduced by colonization).

The one downside to an edit button is shitweasels like Pedo Jeffy would go back and completely change their comments when called out for their lies.

also noticing how multiple states kept pushing the timeline further and further.

That is utter horseshit and lies and you people KNOW IT. Only seven states plus DC ALLOWED third trimester abortions pre-Dobbs for anything beyond extremely narrow restrictions - specifically life of mother for procedures carried out in an ER.

Those states are in my post above. You people have invented shit out of thin air in order to sell fear. Not really a surprise. It's the MO of all politics - and especially politics aimed at the more manipulable lizard brained among the voting base.

Seven states and one district is several. So he didn't lie.

18 states allowed abortion for 'women's health', 'fetal abnormalities' or 'on request' BEFORE Roe. A few more with more restrictive - mother life, rape, incest, etc. Obviously trimesters didn't exist as a legal thang pre-Roe - but just as obviously those states didn't make third trimester abortions illegal either.

Showing both - only NH, VT, and NJ were states where abortion was illegal/highly restricted pre-Roe but now available in third trimester.

On the other side - CA, WA, NY, HI, KS, AR, FL, GA, SC, NC, VA, MD, DE are all states where Roe actually provided a legal basis to restrict third trimester abortions while only 'unrestricting' first trimester abortions.

Still doesn't change the fact that seven and a district is several. So, he didn't lie. Also, trimester was a thing pre Roe (the legal thing is a complete non-sequitor), and if you read the actual Roe decision it addresses that second trimester abortions were subject to severe restrictions while third trimesters were banned except under the most extreme circumstances. It's actually spelled out in the decision.

Finally, we aren't arguing pre-Roe but what has happened post Roe, where even many pro choice activists admit that some of the most extremists continue to push the window covered by Roe up to birth, in contrast to Roe. So, again, his original statement is true, despite your moving the goal posts to prove your point.

You are talking about late-term (third trimester) abortions as a increasingly common and legal occurrence that is a result of some current pro-abortion political activism.

It's simply not true. You are peddling fear. Certainly activists exist who advocate abortion up to birth - or maybe age 18 - or 30 or 65 or 100. So what. They have as much influence as the Easter Bunny worshippers who head to Roswell for conferences with Elvis Presley impersonators and aliens. I'm sure those people are a thing too.

No, that isn't what I am arguing, and it isn't what he stated he, wareagle said some activists where pushing this in several states. And you stayed that's a lie. It isn't a lie. It may only be legal in seven states and one district (which technically can be several) but they have pushed it in several other states without success. Nothing he stated is a lie. And especially everything you've posted as a rebuttal comes nowhere close to proving it's a lie. That's my point.

And your pushing fear and demonizing any of those who disagree with you as I've pointed out several times above. In fact, I've stated nothing that even comes close to fear mongering, I've simply pointed out the fallacies of your arguments.

And I never said it was a growing movement. My response was that nothing you claimed was a lie by wareagle actually is a lie and nothing you posted proves it was a lie. As for your second paragraph, non sequitur much? This is what I mean by you pushing demonization of anyone who dares disagree with you even the least, your entire comment just provided far better evidence than I could. Thank you for proving my hypothesis again.

You're so convinced of your own saintliness that you automatically assume someone pointing out that your arguments are fallacious must be evil, that you can't accept the criticism for what it is. And what it is is that your arguments are no more fact based than the arguments you dismiss out of hand and largely based on getting the other side. You are part of the problem not part of the solution. You are entirely what I and others are speaking against. People so caught up in their own righteousness that they forgive accessed of their side to feel superior to the other side, that it makes the vast majority of both sides, who see nuance, unlikely to reach compromise.

The number of extremists on both sides is fairly equal and the extreme positions are just as extreme, but the vast majority are far more nuanced and getting into debates about extremes is counterproductive.

Rather than label wareagle a liar (a personal attack that gains you nothing, especially as you haven't proven him a liar) it would be far more productive to state, that yes some pro choicers do have extreme views, however, they don't represent my views or most others and they have been mostly unsuccessful. Which your data more strongly indicates. Rather than arguing the dubious need for third trimester abortion, it would be more productive to see what we can agree on. Without the personal and snarky remarks you used above to ask why I felt 16 weeks was appropriate or your attempt to show your opinion of 20-24 weeks was more rationale. You have demonstrated by your actions that you don't want to find common ground but instead want to feel superior to those who don't agree with you.

Again, I think it's about framing. My remark demonstrates this. Both sides want to be seen as reasonable (at least the majority) however, the issue is rarely framed in such a manner. See my comment below about educating farmers and ranchers about conservation methods.

Both sides want to be seen as reasonable (at least the majority) however, the issue is rarely framed in such a manner.

I agree. That's just the thing - the people who see themselves as being on "sides" are the ones who are least likely to be reasonable and the most likely to frame their opponents, because they are opponents, as morally reprehensible people.

The majority of people, who don't see it as black-and-white, aren't out there screaming at one another.

No, but what happens is that the majority tend to get pushed towards extremism by the extremes of their opponents and demonization. Like the debate below about is the right still free markets. The rights views really haven't changed drastically just how it's framed by their opponents has created a much more vitriolic debate, and the actual goals have been ignored, while labels such as populism and nationalism have been applied to them to demonize them, and Reason has fully jumped on that wagon, and has mostly ignored what their actual goals and desires are. They argue against Canadian lumber tariffs often with arguments of "muh cheap lumber", while ignoring why Canadian lumber is cheaper, and how this isn't the result of free markets, but because Canadian and American government interference. That the right wants to curtail this interference, and return to a more free market trading with Canada, which they believe would make American timber more attractive and competitive. Canada doesn't want this, because they know it is likely to occur (Canada does the same thing with American dairy, but even more so, because American dairies are far more efficient and productive). It would be nice if it didn't take government intervention to end these practices, but unfortunately this isn't reality. Tariffs might be the wrong way to achieve these goals too, but there definitely is some role for the US government in these disputes, and it should be aimed at what benefits Americans.

I would also note that the primary reason chattel slavery ever really gained traction in the colonies was because Parliament and the King created policies that promoted it while hindering alternatives.

Thread failure.

Can we disenfranchise people who join political parties?

If only we could get the votes.

It would be nice if it didn't take government intervention to end these practices, but unfortunately this isn't reality.

This is as good a context as any to respond to what you're saying in your longer posts, below.

This is exactly what I'm saying Marx thought, and is exactly what the Republicans are more and more on board with in contrast with the Libertarians (the capital-L ones).

Marx also thought of himself as championing economic liberty - for the working class. Marx also thought that a priori government interference in the economy required more interference as a counterweight to increase the economic liberty of the working class.

The technocratic Democrats that I know also think of government as protecting the economic liberty of employees by regulating the corporations.

Traditionally, Libertarians have opposed all such government interference in the economy, even in cases where a foreign government meddles in markets and creates unfair competition, or where a corporation may take advantage of a glut of immigrants to drive wages down.

I'm not saying one of these views is better than the other, I'm saying, and I think you'll see the truth of this, that in the last 6-7 years a lot of Republicans have been very critical of Libertarian opposition to the various government interventions that you describe in the name of balancing out what other governments are doing.

So I can understand that you object to my saying that Republicans have deprioritized economic liberty, but while you may not agree with the phrasing, it seems like you do see what I'm talking about as far as a rift between Republicans and Libertarians in how to approach "economic liberty."

Do you believe that one of the functions of government is diplomacy? And that a governments focus should be on domestic rather than international needs? Because true libertarianism does recognize that government does have some functions.

If you answered yes to either of those two questions, then doesn't it logically follow that part of diplomacy is opening foreign markets, in fact this was the original purpose of diplomacy.

Even Smith recognized this as a function of government and diplomacy. In fact, he thought this was it's primary purpose. So, my counter argument is that by ignoring this, that your 'true libertarians' aren't actually arguing for free markets free of government interference, but rather for consumerism.

Now, I don't agree necessarily with retaliatory tariffs, and I think many on the right are uneasy with them as well, but I reject the argument that diplomacy to reduce trade barriers and unfair practices is not free markets.

In fact, by ignoring these conditions, you aren't actually supporting free markets but consumerism. Which is separate from free markets. Free markets would let supply and demand set prices, which may result in higher prices, until demand is lessened. In consumerism, your sole purpose is cheapest prices, regardless of how they are obtained. Since the cheap imports are not the result of the market setting prices, what you label economic freedom is actually consumerism, not capitalism.

And I would argue that this isn't true liberalism, or classically liberal. I would argue instead it's actually anti-free markets and economic freedoms, and it's also unsustainable, requiring more and greater government interference as unfair trade practices decrease domestic competition, resulting in decreased GDP, and in order to offset this you have two choices, either confront the unfair practices or have the government replicate them. The only government interference in markets should be aimed at reducing anti free trade practices. I would say this view is far more in line with classical liberalism than what you state libertarian principles are.

I think the idea that low prices are the goal of economic freedom and the sole measure of it, is blatantly shortsighted and actually counter to libertarian principles, as it's not the reality. Instead, economic freedom allows both fair competition and freedom to purchase what you want. Focusing solely on the latter, isn't economic freedom. Because it ignores one half of the coin, which is being able to produce your own wealth such that you can purchase what you want. Economic freedom is both acquiring wealth, and purchasing freedom. If we focus solely on cheapest products, irregardless of why they are cheap, we reduce economic freedom by reducing personal wealth acquisition. And that is where we are at. Which is a far cry from libertarianism.

As I've argued in the past, this is some libertarians greatest detriment, a lack of pragmatism and a focus only on their own needs as opposed to the whole. I think individual freedom and capitalism go hand in hand, however, my measure of economic freedom includes both the ability to be free to compete and acquire wealth, independent of government interference, including foreign governments, and purchasing what I want. Additin

Additionally, I think what you describe as economic freedom argument of libertarianism is far closer to anarchism and that was the real goal of Marx.

Do you believe that one of the functions of government is diplomacy?

Insomuch as one of the functions of government is defense, yes.

And that a governments focus should be on domestic rather than international needs?

If you're talking about economic needs, "no" and "no."

Even Smith recognized this as a function of government and diplomacy.

If what we're talking about is removing trade barriers.

In fact, he thought this was it's primary purpose.

From Smith's perspective, sure, but from the King's perspective, not so much. Smith's argument for the King is, and must be, "and therefore this benefits you, Your Highness."

I reject the argument that diplomacy to reduce trade barriers and unfair practices is not free markets

But this is getting back into semantics.

Diplomacy to reduce trade barriers is a move toward economic freedom, unambiguously, but when you move into "unfair practices" you move into different territory.

I think the Libertarian response to the unfair practices is to look into your own national affairs and suss out what it is that's making our manufacturers so much less competitive than China's, rather than to try to hurt Chinese markets enough that they become as uncompetitive as ours.

Since the cheap imports are not the result of the market setting prices, what you label economic freedom is actually consumerism, not capitalism.

I agree that "lowest price at all costs" is not classical liberalism - I think Cleveland was wrong to use government force to put down the Pullman strikes, for example.

But like I said above, I also agree with your next statement that these practices are unsustainable, which is why I don't think we need to look to our government to restrict trade with China or to try to harm their economy. We need to look at deregulating our own economy.

I think what you describe as economic freedom argument of libertarianism is far closer to anarchism and that was the real goal of Marx.

It was, yes, and he was just as much an idealist about anarchy as any AnCap.

But while I am not an idealist about anarchy, anarchy is my ideal. A government that tasks itself with securing our individual rights to be free from violence and coercion is the best we could possibly hope for, IMHO.

I think the unsustainable part plays domestically as well, if these practices end up destroying our ability to compete and cause manufacturing death.

Reducing domestic policies is something I think libertarians (even the ones I label consumerist) and right wing populists would agree on. I think were the disconnect is, is with regards to foreign governments. Yes, ultimately their models are unsustainable (and yet people keep repeating them over and over, despite historical failures of these policies) but the question becomes will we still have enough of a industrial base to take advantage of their failures? That seems far less clear. Especially given the fact that our government seems far more supportive of hindering domestic production than encouraging it (and then subsidizing it when it fails but never to the degree other countries, even western "capitalists" democracies do). So, it's really the worst of both systems that we currently have, and despite this, American still remains a prosperous country. Imagine what we could achieve if we reduced regulatory hurdles, while negotiating true free trade agreements and eliminating most favored nation trade status (reduce import regulations across the board, while negotiating with willing partners to create truer free trade alliances)?

Like I said I'm not supporting retaliation, and I'm not sure many on the right are easy with them, however, I think what they believe is when our government signs an agreement, they first priority should be how does this benefit our country. I don't care if it benefits Canada (actually I think free trade would be more beneficial in the long run for both) or Timbuktu or Atlantis or whatever, the focus should be at best benefitting America (founded on free trade) at worst neutral, however, I think the recent past seems to be signing into agreements that ultimately penalize America, while achieving less freedom, and rewarding bad actors (Paris Accords anyone?).

The framing of this issue is huge. My wife considers herself to be pro-choice and objects to the pro-abortion label. She considers her support of legal abortion to be pragmatic--it's the classic "safe, legal, and rare" position. When I asked her if she considers abortion on demand up to birth to be a pro-choice or pro-abortion position, she said, "That's not anything I support." I said that abortion up to birth was legal in some states. She said, "Then they've legalized murder in those states. I don't support that, and being pro-choice for me isn't about that." She also thinks it's ridiculous that pro-abortion activists often object to the idea that women are ever conflicted about abortions or ever regret it. She said, "Of course women are often conflicted about this. Of course some women regret it. Claiming women only feel one way about anything is stupid and paternalistic." My wife, however, doesn't pay attention to the minutiae of politics because she considers it depressing and exhausting. She really tries not to devote much brainpower to politics at all. She assumed that the mainstream Democratic party stance was still "safe, legal, and rare." Finding out that the Democratic party leadership support the abortion up to birth standard was eye opening and enraging for her.

Is "Democratic party leadership support abortion up to birth" based on the Schumer bill regarding the nebulous "risk to physical or mental health" language? Or are there a substantial number of actual Democrat party leaders who come right out and say that in as many words (without conditioning it on a serious health risk to the mother or a likely fatal condition in the unborn)?

You ignore those who took the original, now overturned, decision and pushed it to the extreme of birth and even after. Then there is the whole "shout your abortion" as if it's a noble and good thing you ignore. Sorry, but you can find extremes on both sides and we'll see where the symbolic laws end up now that they've become real.

I'm just curious about this ongoing story about polling being really non-predictive on a lot of topics.

Polling is only as good as the underlying assumptions built into the models. Additionally, the results are often unrepeatable (bringing into question the assertions that they are scientific) and are snapshots in time. They also tend to suffer from binary choices which disallow nuance, which most people have on most subjects. As a result they tend to create false narratives. Because people tend to have nuance, they are open to persuasion on topics. For example, I worked with farmers and ranchers, when we presented education on conservation, we received little buy in if we approached it from the angle of environment or climate change, however, if we approached it from the angle of improving soil health, range health etc, and how that improved production, we achieved high buy in. The program didn't change, but the approach mattered.

Never mind the sample population. It’s rarely representative of the relevant population.

>>The election results suggest

59% of the total vote was cast in JoCo.

Where the people are?

Where the motivated voters are. The results simply suggest this was a higher importance for the voters of heavily populated Johnson county. This could be the result of widely accepted idea that this was likely to pass and therefore supporters felt less need to turn out for an uncontested primary, or that abortion matter so little, that they weren't motivated to vote in an uncontested primary. It would be interesting to see what the results would be if they tried again during the main election. I'm not sure it will be different, but trying to draw a conclusion based on a single data point is asinine.

Johnson County is the anomaly in the "Red State" or whatever Sullum is repeating about Kansas today

“Given the poll’s margin of error those results suggested that voters were about evenly divided on the issue.” No Jacob. What suggested that voters were evenly divided were the poll results. I suspect that Jacob has no clue as to what a margin of error means or how it was calculated in this case. Just like every other “journalist” who throws out that statistic without the foggiest notion of what it means.

Democrats / Leftists wearing tee shirts that say "Keep Your Laws off My Body" are gaslighting us.

That is not their position.

They proved that over the last 2.5 years.

No, they are very honest. "Keep your laws off their bodies" is not the same as "Keep their laws off your bodies. Post-modern social Marxism denies any universal principles and equality (not to be confused with "equity").

they may not support full on bans but they don't support making abortion something to be celebrated and encouraged either. And that is exactly what the left and at least one reason staffer wants.

https://www.hollywoodintoto.com/lena-dunham-sharp-stick-abortion-baby-shower/

And that is exactly what the left and at least one reason staffer wants.

One? I thought the entire staff were hardcore leftists.

Nuance is important. Even with leftist. Reason has drifted to the left, even you have admitted that, in the coverage and analysis. On certain topics almost all current writers and editors tend to be hardcore leftists, while being more moderate on other topics. It doesn't change the drift of the magazine, as had been explained. Nor it's abandonment of several libertarian positions, or even handedness. Pointing out the exceptions is more exceptions proving the rule rather than evidence that the majority of the commenters don't have a valid point about Reason's leftward lurch.

However, on abortion, Reason has been fairly militant left for decades, often dismissing out of hand any libertarian argument for being pro-life. I've argued this subject since I've started posting on here back in 2001. So, for abortion the drift is less dramatic, because the starting point was already biased.

On certain topics almost all current writers and editors tend to be hardcore leftists, while being more moderate on other topics.

Like what, other than gay stuff?

Why rehash this? Because you've even stated you've seen it. How about the initial coverage of a certain Supreme Court Nominees sexual harassment charges? Or the initial coverage of a certain Kentucky high schooler's activities in DC? Or coverage of Russian collusion? January 6th? Etc.

I see them reporting with the facts that they have at the time, and their positions evolving as new facts come into play.

No, they report based often on narratives devoid of actual facts. And by the way they choose to frame facts, is as pertinent as what they report. Framing is important. As you've admitted in the past.

In some cases yes. However, being a Nolan Chart guy instead of a linear Left/Right guy, I don't equate deviation from the right's narrative as support for the left's narrative.

They didn't drift from the rights narrative because they never really embraced it. There was overlap, however, the leftward drift is pretty obvious to long time readers.

I agree there has been a leftward drift, however conservatives have abandoned their support for economic liberty which was the common ground that they had with libertarians. So it goes both ways.

No they haven't. See my comments below. Reason has framed it as that, as has the majority of the media, but that isn't really what they have tried to achieve. You can only believe that if you reject the facts that our current system is no longer a free market, that regulatory capture and cronyism, plus centrally dictated globalism, has resulted in centrally dictated economies directed by government and activists class. The right's populism is a rejection of this system, a rejection of government control and interference. They want to reduce regulations, want to reduce the alphabet soup government agencies, reduce crony capitalism to return to a state where the free market can thrive and allow competition. Even Trump's tariffs were an attempt to do this, as their aim was to force China and the EU to remove anti-competitive practices that those states had enacted that made American exports uncompetitive in their markets. Maybe this was a bad strategy, but the driving force wasn't to close American markets but rather to end state practices that resulted in non-competitive. This includes tariffs on heavily subsidized Canadian timber and Chinese steel. In fact, I would argue, by ignoring those non-capitalists practices, Reason is the one who is ignoring free economy. You can argue tariffs are a bad idea while also acknowledging that the aims of the tariffs were to end practices that also were not capitalism, but statism. Instead you and Reason has decided to label it populism and nationalism and decried it as bad. Rather than understanding what they actually want to achieve.

I don't see the world through a left/right political lens. I'm more of a Nolan Chart guy. So stances that the right sees as leftist could still support personal and economic liberty.

Not when they are enforced by government fiat.

Repealing bad laws just doesn't happen. The best we can hope for is new laws that blunt the edges of the bad laws. Which means government fiat. You say you're pragmatic. Do you agree?

No, because new laws tend to create more problems than they solve. Doing away with bad laws or reforming them is possible. It happens far more often than most people understand. However, the media tends to focus instead on decisiveness rather than success.

It happens far more often than most people understand.

I must be most people, because I just don't see it.

I don't see the world through a left/right political lens. I'm more of a Nolan Chart guy. So stances that the right sees as leftist could still support personal and economic liberty.

You're like the moron who not only sits down at the poker table wearing a green visor but says "What?" when everybody who can see the table knows you touch it every time you've got a bad hand. Just retarded.

Like a bad movie villain whom everyone thinks is blind until the protagonist notices them reacting to a reflection or stepping out of the way of something they can't see coming.

On certain topics almost all current writers and editors tend to be hardcore leftists

I think this deserves to be nuanced, too, though.

"Hardcore leftists" is a pretty strong term. I think it's fair to call reason "neo-liberal," but they're pretty far from Jacobin, for example, which would be a more fair target for a term like "hardcore leftists."

They've definitely stopped trying to appeal to Republicans, and their libertarian advocacy for the last several years has been more culture-war oriented than economics or international-politics oriented, which has caused them to drift more into alignment with Democrats than with Republicans in a lot of cases.

Thus, if "Republican" = "Right" and "Democrat" = "Left," then I think it's fair to say that reason has pretty clearly leaned left for about the past 6-7 years.

But these days economically the Republican base is becoming more authentically Marxist, while the Democrats are "leftist" more in the way that China, Inc. is "Marxist" - i.e., constantly using culture war to bolster the fortunes of entrenched capitalist enterprises. Which the hardcore leftists used to call "appropriation."

There used to be a loose alliance between libertarians and conservatives based upon a common desire for economic liberty. Libertarians still support economic liberty.

There still is, however, reason has decided to label the right as populists because the right has rejected the current crony capitalism and centrally dictated globalism. If you actually read the rights stance on these issues, rather than the medias framing, you would see that their complaints are still about over regulations, regulatory capture, punitive taxation etc. They still believe in the free market. What journalists label populism is actually a rejection of corporatism, which really isn't free markets as it hinders competitiveness. As I stated below, even the push for tariffs wasn't to cut off trade but aimed at ending non-competitive practices enforced by state actors like China and the EU. They really were an attempt to achieve free trade. It may have been misguided, but the incentive wasn't a centrally planned economy but rather to return fairness and competition to the market, that was being throttled by state actors.

What journalists label populism is actually a rejection of corporatism, which really isn't free markets as it hinders competitiveness.

I'll respond to you here, because this line really gets at the central point.

This is why I say "economically the Republican base is becoming more authentically Marxist."

When Marx spoke of "Capitalist ideology," exactly what he meant was the conflation of "free markets" with what we would now call corporate crony capitalism. This is exactly why Marx thought the government needed to be overthrown, because the purpose of government is to restrict economic activity for the benefit of certain groups. If you can't get rid of government completely, in Marx's view, you can at least harness it so that it benefits the working class at least as much as it benefits the owning class.

This is pretty much exactly where the Republicans are right now.

But then, as you say above, it all comes back to framing - like the CCP, our owning class is currently engaged in performatively embracing various forms of Marxism in an ostentatious showing of solidarity with working class resistance to the oppression that they themselves are the source of. But they greatly prefer more recent forms of "cultural" Marxism that allow members of the bourgeois to not just see themselves as the "vanguard of the Revolution," but to actually see themselves as the oppressed, with the culturally conservative working class as their oppressors.

What this means in our context is that our domestic champions of the working class against the barons of Wall Street see themselves as anti-Marxists.

Except Marx saw the workers owning the means of production, and the right doesn't want that so much as allowing Adam Smith style capitalism to thrive, which will improve the working conditions and living conditions of the workers. What we really have isn't really Marxism or socialism, it's far closer to economic fascism, in the same strain as what Mussolini implemented. The mirage of capitalism, but directed and supported by the government, which picks winners and losers.

Except Marx saw the workers owning the means of production, and the right doesn't want that so much as allowing Adam Smith style capitalism to thrive