Is Twitter-Famous Princeton Historian Kevin Kruse a Plagiarist?

His 2000 thesis on civil-rights-era Atlanta lifts passages from other people's work.

When former Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke intimated in early 2017 that he would be joining Donald Trump's nascent administration, CNN obtained a copy of Clarke's master's thesis from the Naval Postgraduate School and revealed that Clarke had copied blocks of text from other sources. The borrowed passages, as CNN noted, had footnotes identifying their sources, but they failed to "indicate with quotation marks that he is taking the words verbatim."

Few responses to CNN's revelation encapsulated the giddiness of the academic left more than that of Kevin M. Kruse, a Princeton historian and rising social media star. When the Clarke plagiarism allegations surfaced, Kruse invoked his own credentials to condemn the transgression: "I'm a professor. This is textbook plagiarism." Clarke, he continued, "plagiarized to get an academic degree." When talk radio host Dan O'Donnell pointed out that Clarke had at least footnoted his sources, Kruse wasn't impressed: "We'd expel a student who pulled this."

Known for posting Twitter threads that call out both real and imagined errors of accuracy in conservative commentaries about America's past, Kruse earned the moniker of "History's Attack Dog" from The Chronicle of Higher Education. Kruse parlayed his half-million Twitter followers into a recurring opinion column on American political history at MSNBC, and he will soon be taking his Twitter threads to print in a co-edited book, which purports to catalog "distortions of the past promoted in the conservative media."

But a discovery from Kruse's past may now put Princeton's Twitter warrior under a microscope of his own, raising the question of whether he holds himself to the same standards that he imposes on his internet adversaries. A key passage from Kruse's doctoral dissertation on the history of race relations in Atlanta displays uncanny similarities to a 1996 book on the same subject by Ronald H. Bayor, a now-retired historian from Georgia Tech.

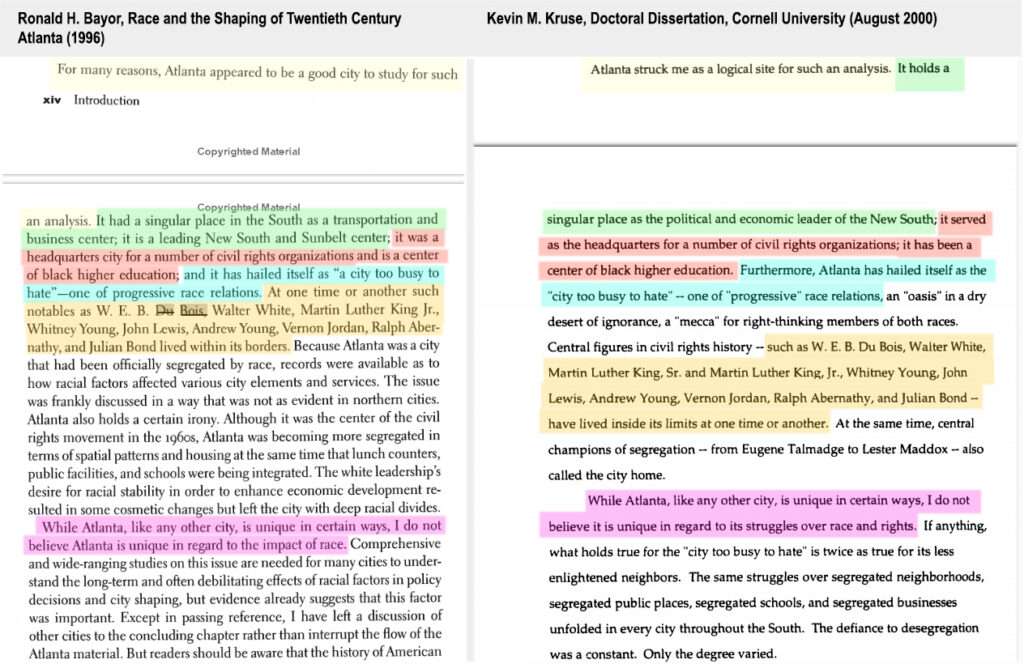

Bayor introduces his academic monograph, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta, by outlining the reasons he chose to study the burgeoning Georgia metropolis: "For many reasons, Atlanta appeared to be a good city to study for such an analysis. It had a singular place in the South as a transportation and business center; it is a leading New South and Sunbelt center; it was a headquarters city for a number of civil rights organizations and is a center of black higher education; and it has hailed itself as 'a city too busy to hate'—one of progressive race relations."

Compare that to how Kruse introduces his dissertation at Cornell four years later: "Atlanta struck me as a logical site for such an analysis. It holds a singular place as the political and economic leader of the New South; it served as a headquarters for a number of civil rights organizations; it has been a center of black higher education. Furthermore, Atlanta has hailed itself as the 'city too busy to hate'—one of 'progressive' race relations."

The similarities do not stop there. In outlining the background for his study, Bayor provides a long list of Atlanta's famous African-American residents: "At one time or another such notables as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond lived within its borders."

Kruse's dissertation repeats the same list, subject only to a minor reorganization of the text: "Central figures in civil rights history—such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter White, Martin Luther King, Sr. and Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney Young, John Lewis, Andrew Young, Vernon Jordan, Ralph Abernathy, and Julian Bond—have lived inside its limits at one time or another."

A few sentences later, Bayor begins to summarize his book's thesis, writing "While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe Atlanta is unique in regard to the impact of race."

Compare that to how Kruse lays out his dissertation's thesis, which holds that Atlanta's experience may be representative of other southern cities in the era of segregation: "While Atlanta, like any other city, is unique in certain ways, I do not believe it is unique in regard to its struggles over race and rights." The only difference in this case appears to be a cosmetic change of the last few words.

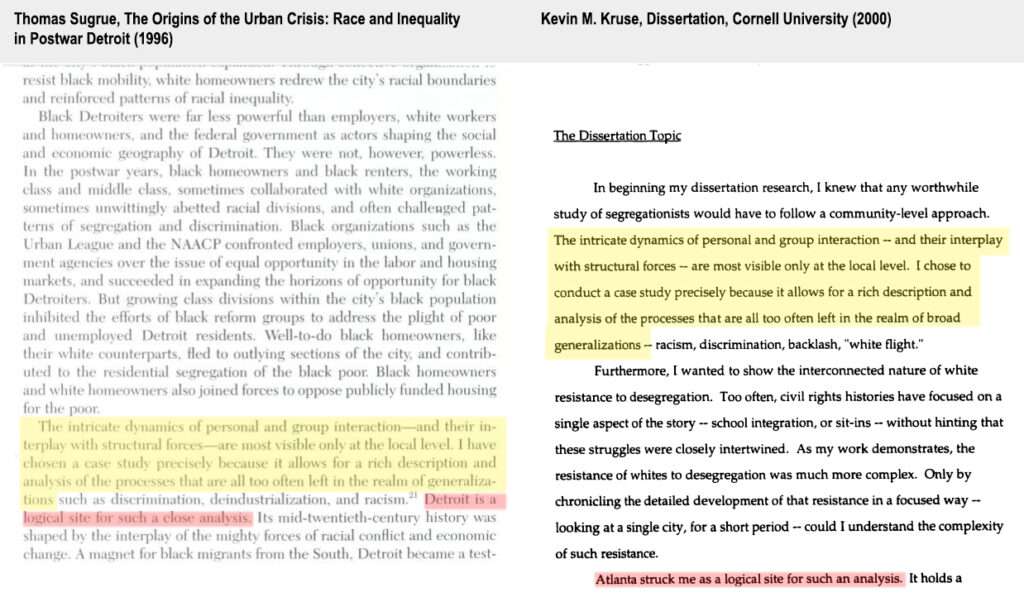

Kruse's dissertation contains other passages with striking similarities to previously published works. Consider this passage from historian Thomas Sugrue's 1996 book The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit: "The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I have chosen a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of generalizations such as discrimination, deindustrialization, and racism."

Kruse uses almost identical language in his dissertation, although he shifts its location from Detroit to Atlanta: "The intricate dynamics of personal and group interaction—and their interplay with structural forces—are most visible only at the local level. I chose to conduct a case study precisely because it allows for a rich description and analysis of the processes that are all too often left in the realm of broad generalizations—racism, discrimination, backlash, 'white flight.'"

Kruse's doctoral research on Atlanta during the civil rights era put him on a fast track to the elite ranks of an Ivy League history department. Princeton offered him an appointment as an assistant professor directly out of grad school, primarily on the basis of this dissertation. Five years later, he converted his doctoral research into a book published by Princeton University Press, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. The monograph won awards from the Southern Historical Association and the American Political Science Association, as well as a string of promotions in the Princeton history department. It also became the basis for Kruse's most famous foray into political journalism, an essay in The New York Times' 1619 Project titled "What Does a Traffic Jam in Atlanta Have to Do with Segregation? Quite a Lot."

It is not clear how much else Kruse borrowed from these two sources—or any other authors—without adequate acknowledgements. At least one of the lifted passages from Bayor's book made its way into White Flight: Kruse presents the same list of famous African-American residents of Atlanta on page 13 of the book, although he slightly rearranges the order. The Sugrue passage has been rewritten in White Flight, where Sugrue's description of segregation as "most visible only at the local level" is now Kruse's "always their clearest at the local level."

I asked Kruse for an explanation of the aforementioned examples from his dissertation. Responding by email, he indicated his "intellectual debts to Prof. Bayor and Prof. Sugrue in the text, endnotes and bibliography" but acknowledged that I had "found instances here in which I inartfully or incompletely paraphrased them. Again, thank you for bringing this to my attention and for giving me the opportunity to respond."

Kruse's scholarship shows other signs of textual borrowing that are careless at minimum, and not unlike what he accused Clarke of doing in the latter's master's thesis. I first encountered similar problems while writing a review of another Kruse book—2015's One Nation Under God—for an academic journal. The book advances a provocative theory that attributes the modern-day presence of religiosity in American politics to what Kruse labels a "Christian libertarian" assault on the New Deal in the 1940s and '50s. It also exhibits sourcing patterns that resemble those in his dissertation.

Kruse's narrative caught my attention when he referenced a relatively obscure quotation from Abraham Lincoln about the printing of the first "greenback" paper U.S. currency during the American Civil War. Kruse wrote: "Lincoln, aware that the gold supply supporting 'greenbacks' was dwindling, joked that a more appropriate motto might be found in the words of the apostle Peter: 'Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have give I thee.'"

Compare the textual structure of this passage to the presentation of the same Lincoln quote by an earlier source, a 1956 essay by Elizabeth M. Fowler in The New York Times: "But it is reported that President Lincoln, mindful of the dwindling gold supply, said that a more appropriate motto for the greenbacks might be the remark of the Apostle Peter: 'Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have, I give Thee.'"

Other elements of Kruse's 2015 book showed similarities to Fowler's prose, with only minor changes; in total, the textual commonalities continue for more than a page. Unlike the situation with Bayor and Sugrue, Kruse's 2015 book does include a footnote with a partial citation to the location of Fowler's article (although he omits any credit of her by name).

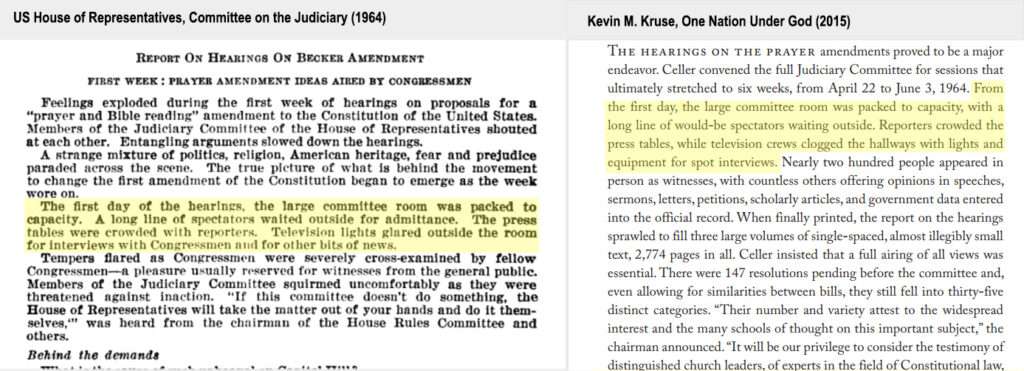

In another example from One Nation Under God, Kruse appears to commit the same scholarly sins for which he chastised Clarke. Describing a House Judiciary Committee hearing in the wake of the landmark school prayer case of Engel v. Vitale, Kruse writes: "From the first day, the large committee room was packed to capacity, with a long line of would-be spectators waiting outside. Reporters crowded the press tables, while television crews clogged the hallways with lights and equipment for spot interviews."

Here is how the 1964 committee report described the same events: "The first day of the hearings, the large committee room was packed to capacity. A long line of spectators waited outside for admittance. The press tables were crowded with reporters. Television lights glared outside the room for interviews with Congressmen and for other bits of news."

As with Clarke's alleged transgressions, Kruse includes a citation to the report in his footnotes. He offers no quotation marks around the borrowed language, and appears to further obscure it with minor cosmetic rearrangements of the report's text. Do passages such as these qualify as "textbook plagiarism," as Kruse charged Clarke in 2017, or a simpler form of sloppiness?

This resembles not only the Clarke case, but also allegations of plagiarism against the prominent historians Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin. Ambrose admitted "mistakes" over similarities between his work and another author's book about World War II bomber pilots, and Goodwin resigned from the Pulitzer Prize judging committee over suspect passages in her books about the Roosevelt and Kennedy families. Both Ambrose and Goodwin referenced their sources but then lifted passages of text with identical phrasing or only minor cosmetic changes.

Such examples suggest a recurring problem in the history profession, which traditionally relies on close textual readings and citation-heavy discussions of other historians as it scrutinizes and interprets the past. The American Historical Association's statement on professional conduct warns that "writers plagiarize, for example, when they fail to use quotation marks around borrowed material and to cite the source, use an inadequate paraphrase that makes only superficial changes to a text, or neglect to cite the source of a paraphrase." Even with proper footnoting, the organization notes by example, plagiarism may still be present. Repeated passages with only "cosmetic alterations indicate a lack of synthesis and original thought and represent a theft of [the borrowed] text."

In Kruse's case, the passages from Bayor and Sugrue may portend more serious problems in the academy. In an age of declining academic rigor, certain works seem to get a pass—provided that they promote particular ideological narratives that enjoy a following among elite academics and journalists.