The FDA's Menthol Cigarette Ban Is a 'Racial Justice' Issue, but Not in the Way Its Supporters Mean

The proposed rule, which targets the cigarettes that black smokers overwhelmingly prefer, will harm the community it is supposed to help.

Supporters of the ban on menthol cigarettes that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed today say it is "a racial justice issue." They are right about that, but not in the way they mean.

What they mean is that 85 percent of black smokers prefer menthol cigarettes, compared to 30 percent of white smokers. "The number one killer of black folks is tobacco-related diseases," Phillip Gardiner, a tobacco researcher and activist, told Slate's Julia Craven after the FDA announced plans for the ban last year. "The main vector of that is menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars."

The FDA's proposed rule would ban both, which the agency says will "address health disparities experienced by communities of color." Action on Smoking and Health welcomed the FDA's ban, calling it "a major step forward in Saving Black Lives" and averring that "menthol advertising violates the right to health of Black Americans."

Although menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes pose similar hazards, the FDA says menthol makes smoking more appealing and harder to quit. As Guy Bentley, director of consumer freedom at Reason Foundation (which publishes this website), noted this week, the evidence on the latter point is mixed. But even if it were clear that menthol smokers are less likely to quit, that would not necessarily mean menthol cigarettes are inherently more "addictive." That debate tends to obscure the tastes, preferences, personal characteristics, and circumstances that are crucial to understanding why some people never smoke, some start but eventually quit, and others continue smoking.

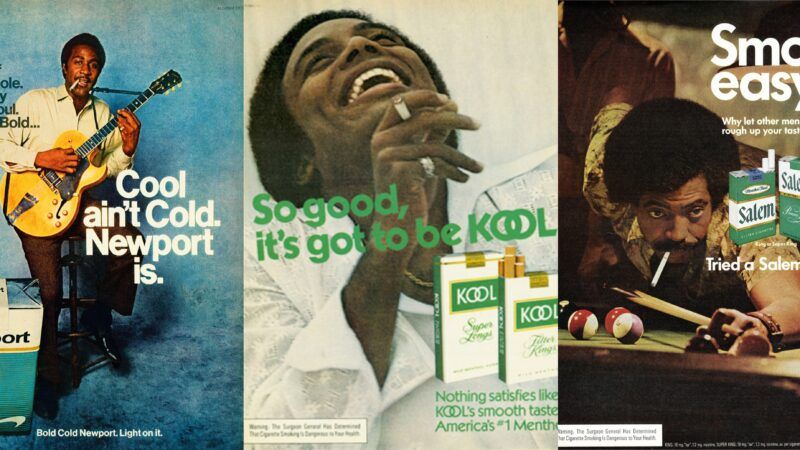

As the menthol ban's proponents see it, even the choice to start smoking is not really a choice, because consumers—in this case, black consumers in particular—are no match for Big Tobacco's persuasive wiles. Gardiner cites the industry's history of "predatory marketing," while the anti-smoking Truth Initiative condemns "relentless profiling of Black Americans and vulnerable populations" by brands like Kool, Salem, and Newport.

That's one way of looking at it. Here is another: The federal government is targeting the kind of cigarettes that black smokers overwhelmingly prefer, precisely because black smokers overwhelmingly prefer them. The FDA also worries that menthol cigarettes appeal to teenagers, another "vulnerable population." Public health officials are thus treating African Americans like children in the sense that they don't trust either to make their own decisions.

"The proposed rules would help prevent children from becoming the next generation of smokers and help adult smokers quit," says Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra. "Additionally, the proposed rules represent an important step to advance health equity by significantly reducing tobacco-related health disparities." The FDA notes "particularly high rates of use by youth, young adults, and African American and other racial and ethnic groups."

The federal government is implicitly denying the moral agency of black people, suggesting that they, like adolescents, are helpless to resist the allure of "predatory marketing" or the appeal of menthol's minty coolness. In the FDA's view, persuasion is not enough to break Big Tobacco's spell; force is required.

The FDA's legal license to prohibit menthol as a "characterizing flavor" in cigarettes comes from the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. That 2009 law, which gave the FDA regulatory authority over tobacco products, banned flavored cigarettes but made an exception for menthol. At the same time, it left the FDA with "authority to take action" against "menthol or any artificial or natural flavor."

According to the menthol ban's supporters, the FDA is doing black Americans a favor by limiting their choices: Without the menthol option, black smokers may decide to quit, and fewer black people will take up the habit to begin with. The FDA says the menthol ban has "the potential to significantly reduce disease and death from combusted tobacco product use, the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., by reducing youth experimentation and addiction, and increasing the number of smokers that quit." Nothing else matters in a "public health" calculus that attaches no value to individual freedom or consumer choice.

In addition to condescending assumptions, the FDA is displaying remarkable shortsightedness regarding the practical impact of its policy on the community it supposedly is trying to help. "Policies that amount to prohibition for adults will have serious racial justice implications," the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Drug Policy Alliance, the Sentencing Project, and 24 other organizations warned in an April 2021 letter to Becerra and Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock. "Such a ban will trigger criminal penalties, which will disproportionately impact people of color, as well as prioritize criminalization over public health and harm reduction. A ban will also lead to unconstitutional policing and other negative interactions with local law enforcement."

The ACLU letter noted that "a menthol cigarette ban would disproportionately impact communities of color, result in criminalization of the market, and exacerbate mass incarceration." The ban "also risks creating large underground, illegal markets." That "would be a massive law enforcement problem for states, counties, and cities, since all states treat unlicensed sale of tobacco products as a crime—usually as a felony punishable by imprisonment."

The FDA glides over that point, instead emphasizing that the agency "cannot and will not enforce against individual consumers for possession or use of menthol cigarettes." But many of those individual consumers will look for ways to continue smoking the kind of cigarettes they like, and that demand will be filled by other individuals, who in turn will be subject to criminal penalties.

The FDA "recognizes concerns related to how state and local law enforcement may enforce their own laws in a manner that may impact equity and community safety, particularly for underserved and underrepresented communities." Its solution is to request public comment on "policy considerations related to the potential racial and social justice implications of the proposed product standards."

The case of Eric Garner, who was killed by New York City police in 2014 during an arrest for selling untaxed cigarettes, gives you some idea of what the menthol ban will mean in practice. Garner's mother, Gwen Carr, is decidedly less enthused than the FDA about the paternalistic potential of banning menthol cigarettes. That policy, she warns, "has consequences for mothers like me," because it will give "police officers another excuse to harass and harm any black man, woman, or child they choose." Unlike the tobacco industry's "relentless profiling of Black Americans," which was limited to product pitches, this kind of profiling will involve armed agents of the state.

While most members of the Congressional Black Caucus voted for a 2020 bill that would have banned menthol cigarettes, there are dissenters. "A ban would possibly lead to illegal and unlicensed distribution," Rep. Sanford Bishop (D‒Ga.) told The Hill this week. "The banning of the menthol cigarettes would certainly push those people who prefer that to the illegal and illicit acquisition of those products."

As the ACLU et al. see it, the FDA is ignoring the lessons of drug prohibition by blithely adding another target to the list of arbitrarily proscribed substances. "Tobacco policy will no longer be the responsibility of regulators regulating, but police policing," they said. "Our experience with alcohol, opioid, and cannabis prohibition teaches us that that is a policy disaster waiting to happen, with Black and other communities of color bearing the brunt."

Such concerns explain why the menthol ban is controversial among African-American organizations, which have arrived at diametrically opposed positions based on clashing visions of racial justice. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) endorsed the FDA's ban, saying "the tobacco industry has been targeting African Americans," thereby contributing to "the skyrocketing rates of heart disease, stroke and cancer across our community." But the ACLU letter attracted support from several African-American groups, including the National Black Justice Coalition, the National Association of Blacks in Criminal Justice, and the National Association of Black Law Enforcement Officers.

Maybe those groups and people like Gwen Carr are seeing something the NAACP doesn't. Although drug prohibition has racist roots and disproportionately harms black Americans, it attracted the support of black politicians who believed they were helping to save their communities from the scourge of drug abuse. That logic explains why supposedly liberal black Democrats like former Rep. Charlie Rangel, who represented Harlem from 1971 to 2017, joined Republicans and white Democrats like Joe Biden, then a Delaware senator, in backing draconian crack cocaine penalties that predictably fell most heavily on African Americans.

The sentencing scheme that Congress created in the 1980s treated smokable cocaine as if it were 100 times worse than the snorted kind, setting the weight cutoffs for mandatory minimum sentences accordingly. It also prescribed a five-year mandatory minimum for simple possession of as little as five grams—less than the weight of two sugar packets. Since blacks accounted for about four-fifths of federal crack defendants but a minority of cocaine powder defendants, the upshot was glaring, racially skewed disparities in punishment for similar conduct.

Black politicians recognized that reality pretty quickly (sooner than Biden did) and began pushing for crack sentencing reform. That effort ultimately led to the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the sentencing disparity between crack and cocaine powder, and the FIRST STEP Act of 2018, which made that change retroactive. By then, members of Congress overwhelmingly agreed that a drug policy supposedly aimed at helping black Americans had done far more harm than good.

The NAACP eventually reached the same conclusion about marijuana prohibition, which it opposes on racial justice grounds. On that issue, unlike the menthol ban, the NAACP and the ACLU are allies.

The insanely punitive response to crack "seemed like a good idea at the time," Rangel says in the Netflix documentary Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy. But in retrospect, he adds, "it was clearly overkill." In a few years, black leaders who supported the FDA's menthol cigarette ban may be saying something similar about that supposedly noble and enlightened policy.