Antiquated Zoning Laws Are Worsening the Housing Crisis

Ending single-family zoning doesn't ban single-family homes from neighborhoods. It merely allows more freedom for people to build what they want.

We've all seen the news stories about the nation's insanely overheated housing market, as bidding wars have become the new normal. Prices have hit record levels and in some markets they have increased 20 percent since the beginning of the pandemic. It's no surprise that "housing crash" is one of the most popular search terms on Google.

California's median home prices have just topped $800,000, which is astounding when one considers that this is the statewide median, and includes lower-cost markets such as Bakersfield and Modesto. Unlike markets for consumer goods, government permitting and land-use regulations depress housing supply. That has led in part to the current price run up.

In 2015, the Legislative Analyst's Office reported that California's housing prices are 2.5 times the national average—and that we need 100,000 more units a year to keep pace. The state's slow-growth rules and endless mandates for solar energy and open space also drive up prices. That's why I beat the same old drum: California needs to let builders construct more housing of all types.

If a proposal reduces government regulations and allows more housing construction, I'm for it. If it does the reverse, I'm against it. That's why I support efforts to allow the construction of multi-family housing in areas that are now zoned only for single-family homes. Despite the misconception, that change doesn't ban single-family homes, but also allows duplexes and condos.

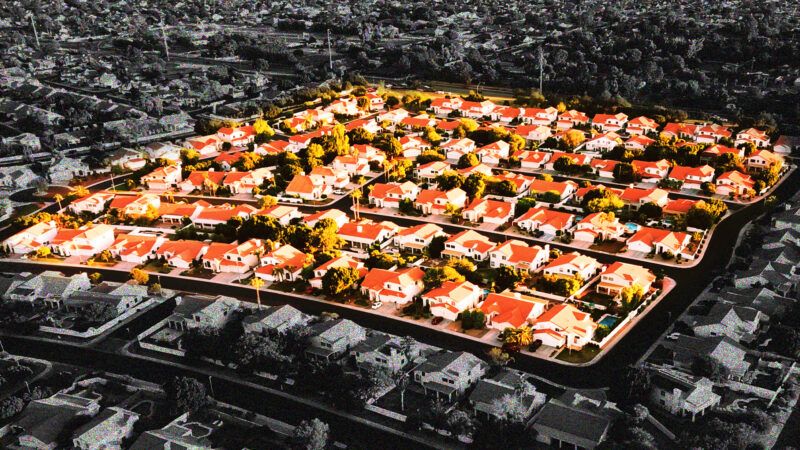

Unfortunately, the housing debate is tied up in the nation's cultural grudge match. To some commentators, efforts to reduce government regulation in the housing area amount to a liberal plot to destroy our God-given right to a lawn and picket fence. In a Fox News column last week, Tucker Carlson portrayed efforts to loosen up zoning laws as an attempt to "eliminate suburbs" and "destroy the lives of people who live in nice places."

Carlson accused the Obama administration of viewing "all those single-family homes—row upon leafy row, set back from the street, well-tended lawns and mailboxes" as examples of "structural racism." In fact, San Francisco designed its first zoning-related law in the 1870s, the Cubic Air Ordinance, to drive out Chinese boarding houses by imposing minimum square-footage rules.

Baltimore passed one of the nation's first zoning laws in 1910. Mayor J. Barry Mahool argued that, "Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidents of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby white neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the white majority." Southern cities used zoning and freeway construction precisely to segregate African Americans.

Instead of stirring up resentment, conservatives could note that the era's progressives devised many of these rules. Mahool was known nationally for his concern about "social justice." Just as backers of early gun-control laws meant them to keep firearms out of the hands of minorities, backers of early zoning laws wanted to keep minorities on the wrong side of the tracks.

Single-family-only neighborhood zoning is a construct of earlier government policy, so there's nothing wrong with adjusting that policy to conform to new realities. Thankfully, various civil-rights laws, court decisions, and changing attitudes mean that anyone can now live in any darned neighborhood they can afford. But history is history.

California's modern progressives have created the state's current housing mess by passing urban-growth boundaries that drive up the cost of developable land, and by fighting construction of suburban developments. They refuse to reform the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which ties up nearly every housing proposal in years of litigation.

They think that building $700,000-per-unit subsidized "affordable" housing projects is the best way to help lower-income people find better housing—rather than allowing the market to work its magic. But some progressives wisely support YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard) land-use reforms, while many conservatives have become NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yarders).

The situation at the local level is bipartisan. Planners typically take what the late UC San Diego law professor Bernard Siegan called the "Mercedes Approach," by which city councils backed by angry residents "try to upgrade proposed developments" by forcing builders to offer more luxurious structures that don't threaten property values.

Fortunately, a San Diego court in May overturned an Oceanside referendum that rejected the council's approval of a housing project. Voters shouldn't decide what others do on their property. By the way, many local officials are apoplectic at a reasonable bill to let developers turn vacant retail centers into housing.

The goal should be to reduce regulations across the board, so builders can more easily respond to market demand by building whatever consumers want to buy. Defending antiquated zoning laws will not accomplish that objective, for the same reason government control of any product or service only distorts the supply and demand process.

Remember that as you get in a bidding war for that $1-million 800-square-foot condo.

This column was first published in The Orange County Register.