Beyond COVID

More uses for new mRNA technology

"You could ultimately use mRNA to express any protein and perhaps treat almost any disease," Moderna President Stephen Hoge told Chemical & Engineering News in September 2018. "It is almost limitless what it can do."

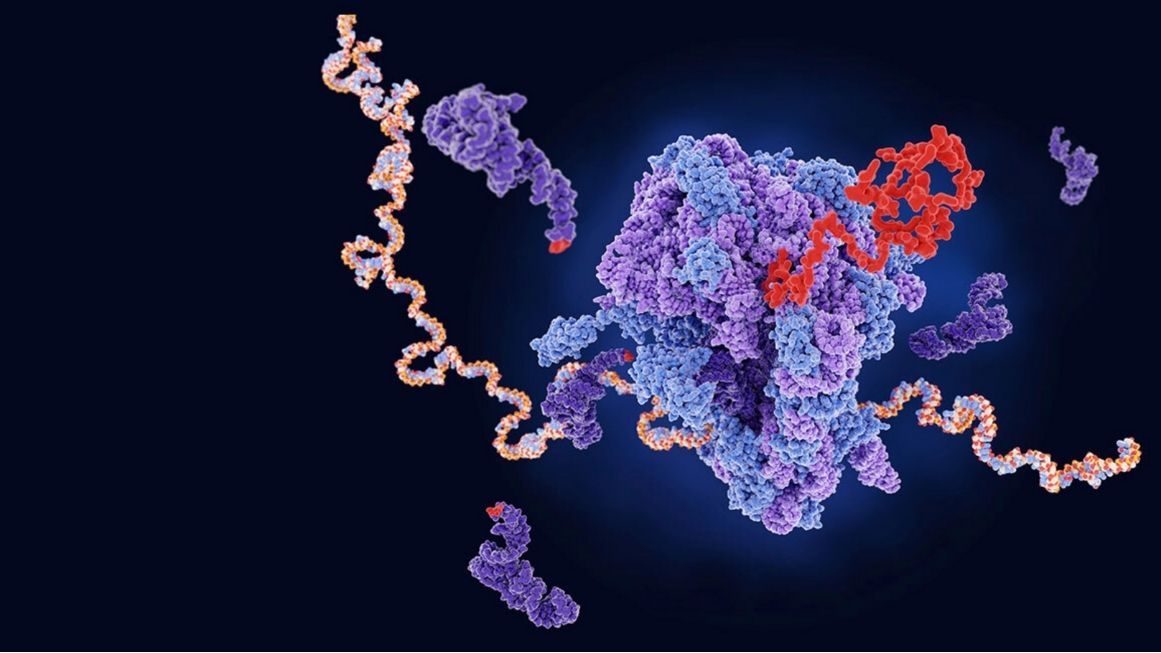

The messenger RNA (mRNA) technology that is at the heart of the first COVID-19 vaccines to be approved is now being aimed at many other infectious diseases for which there are no currently effective inoculations. Moderna, for example, reports early work on vaccines aimed at HIV, Zika, Nipah, cytomegalovirus, and influenza. The German company CureVac, which should soon release the results of the clinical trials for its own mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, is working on vaccines against rabies, Lassa, yellow fever, and malaria, along with a universal flu vaccine.

BioNTech, which partnered with Pfizer to develop a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, is also working on an influenza vaccine but has chiefly returned to its main focus of developing therapeutic mRNA cancer treatments. Just as mRNA vaccines stimulate our immune systems to recognize and attack viruses, researchers are now pursuing mRNA vaccines designed to recognize and attack cancer cells. BioNTech is currently running phase 1 clinical trials for its mRNA treatments aimed at breast, ovarian, melanoma, bladder, and non-small cell lung cancer.

Moderna is developing mRNA tumor treatments, including personalized cancer vaccines that deliver a custom-tailored medicine designed for one patient at a time. The company sequences an individual patient's cancer cells to identify up to 20 different proteins that are not produced in normal cells. Then it creates a vaccine whose mRNAs express the novel cancer proteins, with the goal of training the immune system to identify and attack the patient's tumor.

These personalized vaccines can be combined with other anti-cancer therapies, such as Merck's checkpoint inhibitor drug Keytruda. Such drugs break through the molecular shield that tumors use to hide from the body's immune system. Results from a phase 1 trial reported in November found that the combination was considerably more effective against head and neck cancers than the standard treatment. On the other hand, disappointing results from the colorectal cancer arm of the trial show that mRNA vaccines are not a cancer panacea.

Targeting easily degradable mRNA therapies directly to the sites of solid tumors is also a problem. However, startup Strand Therapeutics uses the tools of synthetic biotechnology to create mRNA molecules that direct their therapeutic payloads to specific tissues and organs. The company has devised mRNA circuits whose biological activities inside of cells can be tuned depending on the size of doses of common medications such as the antibiotic doxycycline.

The therapeutic possibilities of mRNA technology extend beyond infectious diseases and cancers. BioNTech reported in a January article in Science that its experimental noninflammatory mRNA vaccine stopped multiple sclerosis symptoms in mice bred with a condition mirroring the disease in humans, without causing general immune suppression. Researchers at the Center for Regenerative Medicine at Boston University reported the results of a study in which an mRNA vaccine directed liver cells to multiply in order to repair damage to that organ.

In addition, mRNA technologies are being explored as treatments for some inherited diseases. For example, Translate Bio is conducting clinical trials now for its mRNA treatment for cystic fibrosis. The company aims to deliver via nebulizer an mRNA encoding a fully functional version of the defective protein in that lung malady. Moderna is developing mRNA treatments for the inherited metabolic disease phenylketonuria.

One beneficial consequence of the current pandemic is that it supercharged the development of new mRNA treatments that will end up benefiting millions of non-COVID-19 patients in the coming decade.

Show Comments (45)