Suggesting That Face Masks Are More Effective Than Vaccines, the CDC's Director Exemplifies the Propaganda That Discourages People From Wearing Them

Government officials think Americans can't handle the truth, an assumption that tends to backfire.

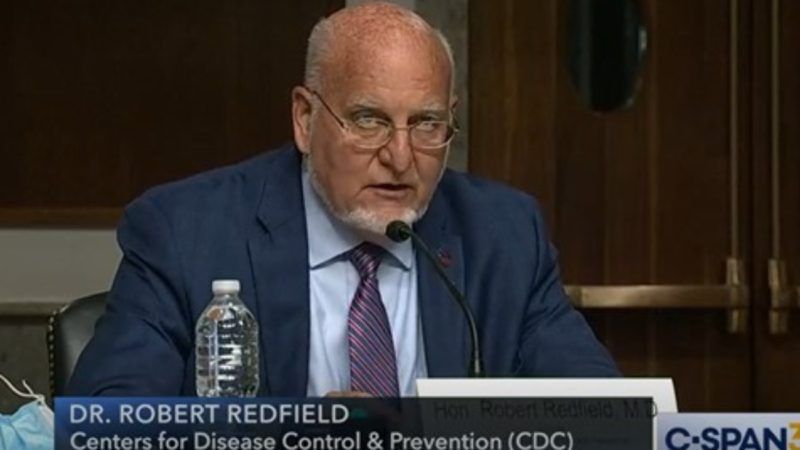

In congressional testimony yesterday, Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), emphasized the value of face masks in preventing transmission of COVID-19. "These face masks are the most important, powerful public health tool we have," he told a Senate subcommittee while holding a cloth mask. "I might even go so far as to say that this face mask is more guaranteed to protect me against COVID than when I take a COVID vaccine."

As The New York Times notes, Donald Trump is notably less enthusiastic about face masks. Redfield "made a mistake" when he said masks provide better protection than vaccines, the president told reporters yesterday. While masks "may be effective," he said, a "vaccine is much more effective."

The Times presents that contrast as another example of the president's resistance to expert advice in dealing with COVID-19. "Trump Scorns His Own Scientists Over Virus Data," says the headline. But the truth is more complicated. Redfield, whose agency initially dismissed the value of face masks worn by the general public, is now erring in the opposite direction by exaggerating the strength of the evidence in favor of that practice. While I believe the evidence is sufficient to conclude that face masks are a reasonable precaution in indoor public places, the case is not as iron-clad as Redfield implies.

Trump's ambivalence about masks is reflected in the mixed messages he has been sending for months.

In a July 20 tweet, Trump called wearing a face mask in public "a patriotic duty." He amplified that message at a press briefing the next day. "We're asking everybody that when you are not able to socially distance, wear a mask," he said. "Whether you like the mask or not, they have an impact. They'll have an effect. And we need everything we can get."

More recently, Trump has expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of face masks. "The concept of a mask is good," he said during an ABC-sponsored Q&A with undecided voters on Tuesday night, "But it also does—you're constantly touching it. You're touching your face. You're touching plates. There are people that don't think masks are good."

That objection to masks, like the concern that people will not wear them properly, does not address the basic question of how we know that masks, when used correctly, help prevent virus transmission. Nor does it address Redfield's claim about the relative effectiveness of masks vs. vaccines.

In late June, about three months after the CDC began recommending general mask wearing, six COVID-19 researchers published a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence supporting that practice in The Lancet. "Face mask use could result in a large reduction in risk of infection," they reported, although they expressed "low certainty" in that conclusion. They noted that "N95 or similar respirators" were more strongly associated with risk reduction than cloth masks of the sort that Redfield displayed at yesterday's Senate hearing. The evidence was limited to observational studies, since the authors found "no randomised controlled trials." But overall, they concluded, the data "suggest that wearing face masks protects people (both health-care workers and the general public) against infection."

In July, CDC spokesman Jason McDonald noted that "data are limited on the effectiveness of cloth face coverings" and "come primarily from laboratory studies." But it is reasonable to believe, based on the limited evidence, that a cloth mask is better than nothing when it comes to intercepting respiratory droplets emanating from a mask wearer or from other people. A mask need not be completely effective to do some good.

"Masks, depending on type, filter out the majority of viral particles, but not all," notes a study published by the Journal of General Internal Medicine in July. But even when masks do not prevent virus transmission, they may reduce the "dose of the virus for the mask-wearer," resulting in "more mild and asymptomatic infection manifestations." The CDC's current advice says "wearing masks can help communities slow the spread of COVID-19 when [masks are] worn consistently and correctly by a majority of people in public settings and when masks are used along with other preventive measures, including social distancing, frequent handwashing, and cleaning and disinfecting."

What about Redfield's suggestion that masks are better than vaccines? He said a vaccine might provoke an immune response in 70 percent of the people who receive it. "If I don't get an immune response, the vaccine is not going to protect me," he said. "This face mask will."

Given the variable effectiveness of different mask types and the limited overall evidence, that is clearly an overstatement. The way the Times frames the issue is even more misleading. "Vaccines are not 100 percent effective," it says, "whereas masks, worn properly, do what they are designed to do." Neither masks nor vaccines are "100 percent effective." The question is which strategy works better to control the epidemic: widespread mask wearing or widespread immunity created by a combination of vaccines and prior infection.

The honest answer is that we don't really know, since that comparison depends on how effective cloth face masks actually are and how effective vaccines prove to be. But we don't actually have to choose between those two strategies, and in practice we are pursuing both. Face masks are a tool to reduce virus transmission, especially to people who face the greatest risk from COVID-19, while we wait for vaccines that we hope will work well enough to make such precautions unnecessary.

Government officials tend to oversimplify science, ignoring nuances and glossing over uncertainty, in the interest of sending clear public health messages aimed at encouraging behavior they believe will reduce morbidity and mortality. But that approach can backfire when officials make statements that clearly go beyond what we actually know.

In July, when Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer wrote a New York Times op-ed piece urging Trump to impose a nationwide face mask mandate, she asserted that "wearing a mask has been proven to reduce the chance of spreading Covid-19 by about 70 percent"—a claim for which there is no scientific basis. Any mildly skeptical person who investigated Whitmer's factoid would have quickly discovered it is unsupportable. That hardly seems like a smart strategy for persuading people who are leery of face masks that wearing them is a good idea.

Likewise with Redfield's comparison of face masks and vaccines. What he should have said is that the evidence, while inconclusive, indicates that wearing face masks when you are indoors with strangers helps protect them, since you may be carrying the virus without realizing it, and may also protect you. Americans may bridle at blatant exaggerations, but that does not mean they can't handle the truth.

Show Comments (241)