The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

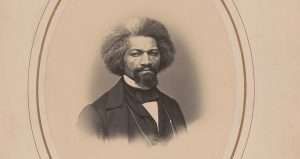

Slavery, the Declaration of Independence and Frederick Douglass' "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"

Douglass' classic speech is an indictment of slavery, racism, and American hypocrisy - but also includes a great deal of praise of the American Revolution.

July 4 is an appropriate time to remember Frederick Douglass' famous 1852 speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" The speech is - for good reason - most famous for its powerful condemnation of slavery, racism, and American hypocrisy. But it also includes passages praising the American Revolution and the Founding Fathers. Both are worth remembering.

Here is, perhaps, the best-known part of the speech:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

And there is much more material of the same kind in the speech, ranging from a denunciation of the internal slave trade, to an attack on the then-recent Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The key point is that slavery and racism made a mockery of America's professed ideals of liberty and equality. And, sadly, that legacy is far from fully overcome even today.

But Douglass' speech also includes passages like this one, praising the American Revolution:

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men too — great enough to give fame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.

They loved their country better than their own private interests; and, though this is not the highest form of human excellence, all will concede that it is a rare virtue, and that when it is exhibited, it ought to command respect. He who will, intelligently, lay down his life for his country, is a man whom it is not in human nature to despise. Your fathers staked their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor, on the cause of their country. In their admiration of liberty, they lost sight of all other interests.

They were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was "settled" that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were "final;" not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men. They were great in their day and generation. Their solid manhood stands out the more as we contrast it with these degenerate times….

Their statesmanship looked beyond the passing moment, and stretched away in strength into the distant future. They seized upon eternal principles, and set a glorious example in their defense. Mark them!

Elsewhere in the speech, he also praises the revolutionaries' refusal to submit to oppression merely because it was backed by law. This is an obvious reference to the those who, in the 1850s, argued that abolitionists had a duty to submit to the Fugitive Slave Act and other unjust proslavery laws. It is also a rebuke to "just enforce the law" arguments backing submission to deeply unjust laws in our own day.

Douglass recognized that the American Revolution not only espoused high principles, but had actually made important progress in realizing them - even as he also condemned the failure to realize them more fully, and the hypocrisy of Americans for tolerating the massive injustice of slavery, which so blatantly contradicted those principles.

In other writings and speeches, Douglass also praised the antislavery potential of the Constitution (which, I think, he in some respects overstated). His purpose in the Fourth of July speech, was not to denounce the Founding Fathers, but rather the white Americans of his own time.

This raises the question of how we should think about slavery and the American Revolution today. Elsewhere, I have argued that, on balance, the Revolution gave an important boost to the antislavery cause, in both America and Europe - most notably by inspiring the "First Emancipation" - the abolition of slavery in the northern states, which was an essential prerequisite to eventual nationwide abolition.

I do not, believe, however, that this fact completely exempts the Founders from severe criticism on their record with respect to slavery. Most obviously, they still deserve condemnation for the fact that many of them were slaveowners themselves. People like Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, James Madison, and George Mason all owned slaves throughout most of their lives, even though they well knew it was wrong and a violation of their own principles.

Jefferson famously denounced slavery as "a moral depravity" and "the most unremitting despotism." Yet he kept right on owning slaves. The same goes for the others, though Washington did finally free his upon his death. It's hard to avoid the conclusion that they continued to perpetrate a grave injustice because they did not want to suffer the loss of wealth and social status resulting from manumission.

This isn't even a matter of "judging historical figures by modern standards." It is a matter of them failing to live up to their own standards.

In addition to failing to free their own slaves, most of the Founders also failed to prioritize the abolition of slavery as an institution. They did take some important steps, such as promoting abolition in the northern states, barring the spread of slavery to the "Old Northwest," and eventually banning the importation of new slaves from abroad. But they pretty clearly did not give abolishing the greatest moral evil in the new republic the priority it deserved.

Instead, they often prioritized less significant, but politically more advantageous issues. Alexander Hamilton (who was not a slaveowner) is often praised for his antislavery attitudes - in some ways justifiably so. But, throughout his political career, he repeatedly subordinated abolition to other priorities. Much the same can be said of most other political leaders of the day.

With great power, comes great responsibility. When it comes to slavery, most of the people who wielded great power in revolutionary America and the early republic failed to fully live up to theirs.

But the condemnation they deserve for that failure must be balanced against the very real progress they made possible - including on the issue of slavery. In addition, we should remember that we ourselves may not be free of the same types of faults.

It is far from unusual for people to set aside principles when they collide with self-interest. How many of us really prioritize doing what is right when doing so requires us to pay a high price? We like to think that, if we were in Jefferson's place, we would have freed our slaves and prioritized abolition. But it is far from clear we would actually have the courage and commitment to do so.

Modern politicians, too, rarely prioritize the most morally significant issues ahead of those that are most politically advantageous in the short run. Given that slaves could not vote - and neither could many free blacks - it is actually notable that the Founders did as much to curb slavery as they did, even if it was nowhere near as much as they should have done.

In sum, Frederick Douglass was right to praise the American Revolution, and right also to condemn the gross injustice and hypocrisy of the nation's failure to live up to its principles. In thinking about the Founders today, we too should praise the great good they did - which ultimately outweighed the harm. But we should also remember their greatest shortcoming. And we should be wary of too readily assuming that we ourselves would do better if faced with the same kinds of choices.

UPDATE: In previous posts, I have written about Douglass' underappreciated speeches on immigration and how we should remember the Civil War.

Show Comments (193)