The Myth of the 'Opium War'

The vast majority of opium users in China were not the desperate addicts portrayed by proponents of prohibition.

Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age, by Stephen R. Platt, Knopf, 592 pages, $35

Stephen R. Platt believes that the so-called Opium War of 1839–1842 was one of the most "shockingly unjust wars in the annals of imperial history." The central question, he writes in Imperial Twilight, is a moral one: How could Britain—a country that had just abolished slavery—so hypocritically turn around and push drugs onto "a defenceless China"?

Platt, a University of Massachusetts Amherst historian, thus joins a long list of writers who have portrayed the Opium War as one of the worst crimes of the modern era. Karl Marx, for one, believed that the slave trade was merciful compared to the opium trade. Forty years ago, John King Fairbank, doyen of modern Chinese studies, called the opium trade "the most long-continued and systematic international crime of modern times."

If this were so, one wonders why the production, trade, and use of opium were entirely legal in such places as Turkey, Egypt, Persia, and India for decades both before and after the Opium War. One wonders why the drug's cultivation spread in the second half of the nineteenth century to the Netherlands, France, Italy, and the Balkans. One also wonders why, as Virginia Berridge revealed in her pioneering 1981 book Opium for the People, up to 100 tons of the substance was imported every year into England, where it was readily available until the end of the 19th century, commonly administered even to children in the form of laudanum.

The author claims that opium was recreational in China but medicinal elsewhere. But this is a dubious distinction, one not even made in Britain—a country where, before 1900, alcohol, tobacco, and opium were all viewed as both palliatives and stimulants. In the absence of modern medicine, all too often pleasure meant absence of pain, especially in a poor and largely agrarian country such as China. Opium allowed ordinary people to relieve the symptoms of such endemic diseases as dysentery, cholera, and malaria and to cope with pain, fatigue, hunger, and cold.

And the vast majority of opium users in China were not the desperate addicts portrayed by proponents of prohibition. They were occasional, intermittent, light, and moderate users—a far cry from Thomas De Quincey, an English writer who famously ingested truly gargantuan quantities of the substance. Platt quotes De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater at length to invoke the horrors of addiction, but surely he realizes that De Quincey was one of the 19th century's most eccentric addicts. (Then again, he appears ignorant of the fact that, despite the title of his book, De Quincey did not eat but rather drank opium, mixed with a bottle or two of strong spirits per day in his periods of heavy dependence.)

Readers, Platt tells us, have long been treated to triumphant accounts of how the West vanquished a "childish people who dared to look down on the British as barbarians," with China appearing as no more than a caricature of "unthinking traditions and arrogant mandarins." The author, instead, promises to "give motion and life" to the changing China of the early 19th century.

I am not sure which "triumphant accounts" he has in mind. There is no dearth of historians who have written engagingly about the events leading up to the Opium War. Dozens of titles fit the bill, some going back more than half a century. Surely Frederic Wakeman Jr.'s Strangers at the Gate (1966) is a model, in style and in substance, although the book is apparently not worthy of mention in Platt's bibliography. Another classic is Peter Ward Fay's well-crafted The Opium War, 1840–1842 (1975), a 500-page magnum opus with all the telling detail required to bring the era back to life.

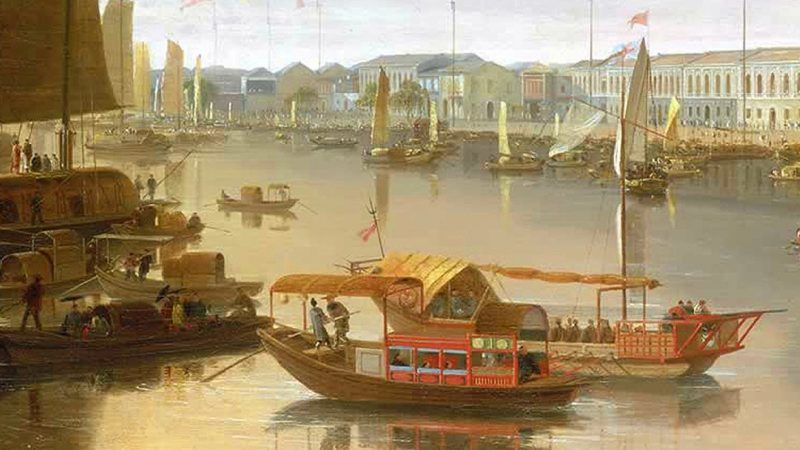

What Platt's book offers is a competent and entertaining, if somewhat meandering, account of British efforts to open up the Qing empire to foreign trade. Foreign merchants were confined to a small settlement in the southern port of Canton, where they had to negotiate with the government officials who maintained a virtual monopoly over the market. The import of opium, as well as saltpeter, salt, and other commodities, was forbidden, as were exports of a range of other products, from rice, copper, and iron to timber.

In consequence, there was a thriving black market from which many profited, not least the officials who used their monopoly to line their own pockets. For decades before the Opium War, foreigners tried to break through these constraints. Platt devotes several chapters to these adventurers, traders, missionaries, and diplomats: the failed Macartney embassy of 1793, the Scottish merchants William Jardine and James Matheson, the linguist and scholar George Staunton, the British superintendent Charles Elliot. This is well-trodden ground, even if Platt tells his tale ably.

The book's subtitle is The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age. This is somewhat puzzling. China, Platt reminds us in a short paragraph, was a powerful, prosperous, dominant country in the 18th century (an empire of "almost unimaginable height"), viewed with admiration by Europeans. But the notion of a golden age rapidly disappears from view as it becomes clear that by the turn of the century, the Qing empire was racked by rebellions, piracy, and corruption on a staggering scale.

Decades of tension in Canton over issues of trade, jurisdiction, and sovereignty came to a head in 1839, after the emperor rejected a proposal from his own advisors to legalize and tax opium. His envoy seized a vast amount of the substance and trapped foreign merchants and their families in the settlement of Canton without charge or trial. Up to this point, no British official disputed the Qing empire's right to control its borders and determine which foreign goods should be admitted. But now, even George Staunton, who opposed the opium trade and had spent his career defending the sovereignty and dignity of the Qing, believed that force was required.

Others objected to retaliation: In a well-known speech reproduced in Imperial Twilight, a young William Gladstone declared in the House of Commons that he could not think of "a war more unjust in its origins."

A single frigate was sent to protect merchants and civilians, followed by an expeditionary force. By 1841, following more talking than fighting, both sides had negotiated a deal in Canton, which London and Beijing then rejected. Time and again, as Julia Lovell showed in her 2014 book The Opium War: Drugs, Dreams and the Making of China, the British tried to inform their adversaries of their demands, but the dispatches the emperor's underlings in Canton sent to the court in Beijing were fictitious. Two years into the war, the emperor still thought it was a mere skirmish and wondered where exactly England was on the map.

The Treaty of Nanjing was finally signed in 1842. It did not mention opium. England had gone to war to protest the arbitrary detention of British subjects and the confiscation of their private property. By 19th century standards, this was a legitimate reason for military engagement. Not until after the fall of the Qing in 1911 did a new generation of nationalists in the Republic of China come to see the agreement as unequal.

Even before the treaty was ratified, the former president of the United States, John Quincy Adams, commented in a lecture before the Massachusetts Historical Society that opium was a "mere incident to the dispute but no more the cause of the war than the throwing overboard of the tea in Boston harbour was the cause of the North American revolution." It is a conclusion shared by many subsequent historians, including Peter Ward Fay and Frank Welsh, but evidently not by Stephen Platt.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

We could use another opium war in China.

I've always considered the real problem with the opium wars was the British racism which figured it was ok to force trade on the Chinese government against their will. Didn't the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 establish that governments were sovereign within their borders; that if a king went Protestant and forced his subjects to go Protestant too, for instance, that was his business and every other country could not interfere? The 1800s British would never have violated a white government's sanctity the way they did to the Chinese.

Whatever one thinks of governments, borders, wars on drugs, and individual liberty, the racism of the Opium Wars is what stands out to me.

Better a racist exception than no exception.

Wasn't it better when enslaving white people was outlawed, rather than allowing all races to be equally enslaved? When the future states of the USA limited slavery to blacks, they had most of the problem licked.

I don't mind when we gain freedom for non-libertarian reasons, like when society decided cannabis was safe enough to allow people to have it. If we could liberate slaves because whites don't deserve slavery, why not?

I'm also in favor of all tax loopholes. The more we can have of them, the better.

The Chinese were at least as racist: they treated the British diplomats (despite Britain being objectively a much more powerful country) as inferiors, demanding constant deference abs tribute, and regarded them with utter contempt as s people. Somehow everyone had forgotten that Europeans did not invent the idea of racial supremacy. In any case, the British actually humored the Chinese superiority complex for awhile until they started imprisoning British merchants.

It’s certainly true that it was a violation of Qing government sovereignty, but that still leaves us with the question of whether the violation of a repressive government’s Sovereignty that impedes its repression is really worse than the repression itself.

OK. But the article maintains that the casus belli was that "England had gone to war to protest the arbitrary detention of British subjects and the confiscation of their private property."

Do you refute that? Genuinely curious, as I know little about this particular conflict.

If you insist on reading in racial collectivism, know that opium paid over 5% of the cost of keeping India under British rule, and Cornwallis was sent there after Washington kicked his ass. Also, the Brits insisted in treaties that China ban local poppies as baaad, thus assuring the smuggling trade. Finally, you know how native Americans lack alcohol-handling enzymes? Might it be possible some such difference makes Asians more susceptible to the allure of opiates?

Without reading the article (I'll get to it later) I'll say that, at least viewed just on this one matter, the British were the good guys, fighting for free trade against protectionism. If you can militarily defeat another country to get them to drop a tariff or non-tariff barrier, why not?

The British had a comparative advantage, being able to produce opium in India that would undercut the domestic price in China, so the Chinese government responded by banning the import. Their own opium makers wanted that market to themselves. So, war for free trade, for the benefit of consumers in China.

One could make the same argument for why the Chinese should resist our protectionist admonishments re fentanyl.

Personally I can think of a ton of free market uses for fentanyl. Mixing it with the glue on the back of stamps so that no one ever need feel the sting of paper cuts. Restaurants that market themselves as cheap alternatives to going to the doctor for pain with such products as eg a French restaurant with Painless Pain. Or Stop Your Kids from Whining Lollipops.

After all, fentanyl is the only drug in the world that is cheaper in the US than in the Third World. But it is still far too expensive to make its way into being used as a nice cheap food filler. And the only way to ensure that broader usage is to eliminate our protectionist and prohibitionist sentiments which have no place in a rational world of homo economicus.

And? Yes, one certainly could argue that the incarceration of foreign drug traffickers is indeed a wrong on the part of the US, and foreigners have the right to try to circumvent the US’s restrictions. So...?

Serious question - do you anarchists actually believe you are rational?

Assuming he’s not entirely an anarchist, then yes.

Fentanyl is not an inherently dangerous product, unlike ricin, and even ricin has medical potential for the targeted killing of cancer, we just haven’t figured out how to administer it safely yet. Even comparing other typical poisons most have medical uses. Curare is used in surgeries, and strychnine was used in a variety of treatments until we figured out that the useful dose was so close to the fatal dose and there were alternatives that were just as good.

The problem the US has with fentanyl (and it’s stronger derivative, carfentanyl) isn’t the drug itself, it’s the adulteration. When a day laborer gets home from his 12 hours of physical labor and injects his heroin that’s a mostly medicinal use - he’s taking it so that he can be productive and get some sleep. The same applies when he takes his methamphetamine in the morning. But when his heroin actually contains fentanyl because it’s cheaper to produce and our legal system prohibits using the courts to remedy fraud he doesn’t get the relief he’s expecting, and when his dealer slightly mis-measures the amount of fentanyl he dies - precisely because he got a heroin-sized dose of a drug that works similarly but is many times stronger.

If we want to cut down on unintended fentanyl deaths we can just make the things people actually want available, and with remedies for fraud. Some people will still choose fentanyl because it’s cheaper, mostly the same who choose malt liquor, but once their income rises they’ll pick something that’s more agreeable to them, like heroin or cocaine, as fentanyl has such a short half life that recreationally it’s just not a useful drug. This is also why it’s so useful in an emergency setting - you can inject a woman on the delivery table for an emergency episiotomy, have it take effect almost instantly, and return her to normal function all within a few minutes of each other.

Problem is - 'remedies for fraud' don't actually work in the real world when the evidence gets eaten and the plaintiff gets dead and the defendant has the protection of presumed innocence (and almost inevitably far more money than the now-dead plaintiff). And fuhgeddaboutit if the defendant is in China exercising some 'right' to circumvent US restrictions re say 'fraud'.

Do you think it's okay for the grocery store to send armed agents to force you to buy Twinkie's? Free trade uber alles!

I wish we could say today, "You let your subjects buy imported goods at competitive prices, or we'll kill you," and mean it. If there's ever a just war, it's war for freedom — and by "freedom" I don't mean national sovereignty. If the Chinese could credibly threaten to kill Congress members if they didn't drop trade barriers, I'd be for that too.

Assuming I suppose that the Chinese had no trade barriers of their own,and didn't raise a stink when foreigners returned the favor.

I don't care whether they raise a stink or not. If two people are killing each other, it's better one of them be stopped than that they each succeed.

Sure - nothing screams liberty like forcing regular people into war in order to further the interests of multinationals who believe they are above all mere 'national' law.

That is precisely what the Brits told the Chinese. The Quing reacted the way "our" Kleptocracy would react were Switzerland to demand that Congress repeal all restrictions on LSD on pain of violent coercion.

While I do love violence as much as you apparently do, I generally believe that it's use should be saved as a means of last resort.

Confucius say: "Man who talk in palindrome mord nil ap nik lat oh w nam."

You ever see the boardgame An Infamous Traffic, Frank?

I recently read Platt's Opium War AND Autumn... story of the Taeping war and came to opposite conclusions from the scholar under dictatorial control. There is a lot in both books many would rather you didn't know. Since Brian Inglis, Jack Beeching, W.A.P. Martin and others began disclosures, the coincidence of the Mutiny with foreign coercion of China, and how handily the burning backdrop assisted U.S. Minister Townsend Harris to get Japan to sign anything he wanted, have raised eyebrows. Platt's work uncovers facts enormous effort has gone into concealing, and both books are excellent, masterfully written and well-researched. Hong Kong's masters can for now still shield the digitized post-Quing Peking Daily News from prying eyes eager for causes of the Balkan Wars and WWI. But the Opium/Taeping conflict era is out of the bag. Rotsa ruck suppressing that.

Opiate users, even those addicted can function quite well for a very long time. That is why people are often shocked to learn that a family member or co worker is one when they OD or something.

when you say "the author believes.....", are you referring to platt or berridge ? you had mentioned both up to that point.

when you say “the author believes…..”, are you referring to platt or berridge ? you had mentioned both up to that point.