John Delaney Won't Be President, But His Health Care Proposal Is Worth a Look

He might not be polling well, but his proposal on health care draws on work from prominent libertarian economists.

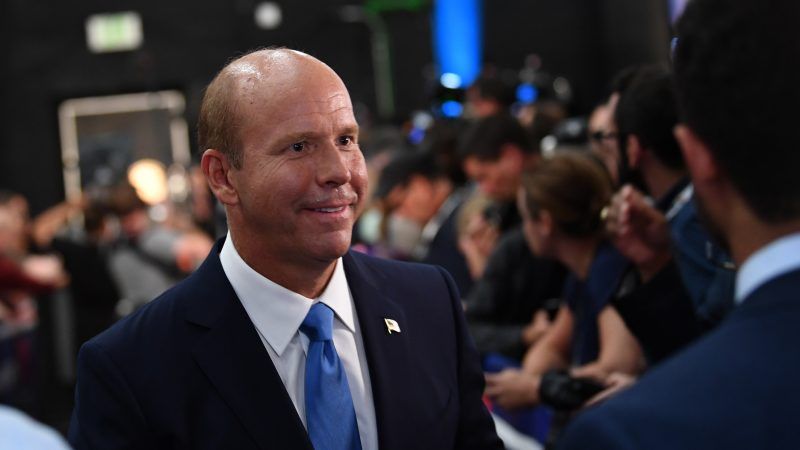

Former Maryland congressman John Delaney might not be polling very well in the Democratic presidential primary, but his health care policy deserves a look.

In Wednesday's Democratic presidential debate, Delaney pushed back against Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.) and other candidates proposing single-payer healthcare plans that would abolish private insurance.

Delaney's plan also calls for universal health care, dubbed "BetterCare," but with a key difference: His plan would be a catastrophic insurance package that would cover only major, high-cost medical expenses. Everyone under the age of 65 would be enrolled, with individuals given the ability to opt-out and use a tax credit to purchase their own insurance. Those enrolled in the program would be free to purchase supplemental insurance, either individually or through their employers. His proposal calls for the new insurance system to absorb both Medicaid and Affordable Care Act subsidies.

Delaney calls health care a "fundamental right," but his proposal for providing it to everyone draws on some libertarian economic ideas.

The late economist Martin Feldstein, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under Ronald Reagan, proposed a version of universal catastrophic care in The Public Interest in 1971. Feldstein argued that health insurance's main purpose should be to prevent financial hardship, and as such, should be focused on covering major, unexpected events. In other words, health insurance should work like car insurance: you don't use car insurance to pay for an oil change, and you shouldn't use health insurance to pay for routine care.

University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman endorsed the idea of universal catastrophic insurance in 2001. He argued that universal catastrophic insurance would free up the rest of the health care system to work as a real market, with patients paying for most health care directly through health savings accounts rather than with a complicated bureaucracy of insurance companies and government programs.

Delaney's plan also helps challenge the system of employer-based health insurance.

Many opponents of single-payer healthcare (including Delaney himself) like to point out that some Medicare for All proposals would force people off insurance plans that they like and which they obtain through their employers. But the reality is that the employer-sponsored health insurance system only exists as a result of World War II-era wage and price controls.

Delaney's plan would allow people to continue using their employer-sponsored insurance if they would like, while eliminating the government-imposed preferences for it, by treating employer-sponsored insurance plans the same way as ordinary income in the tax code.

There are undoubtedly potential problems with Delaney's idea. Even advocates of universal catastrophic coverage acknowledge the difficulty of the transition process. As Johns Hopkins professor Steven Teles has noted, the American health care system is something of a "kludgeocracy," an awkward regime of many ill-assorted, different parts struggling to work together to achieve the goal of providing health care. A universal catastrophic insurance program would get rid of a lot of those fragmented programs, but the complexity of the existing system means that those administrative costs of transition would be high. And from a political perspective, Americans tend to be pretty recalcitrant when it comes to changing the health care status quo—from Obamacare to repealing Obamacare.

However, when compared to leading Democratic proposals for abolishing private insurance entirely, not to mention the $32 trillion price tag on Medicare for All, Delaney's approach at least attempts to address flaws in the existing system while allowing for the possibility of market-based reforms.

Show Comments (40)